Voice-Over Narration—How to Get it Right and How to Get it Very Wrong

A common piece of advice given to newer screenwriters is: avoid voice-over narration at all costs. This can be confusing for the fresh-faced writer. After all, many of their favourite films feature movie voice-over.

Not only that, but many of their favourite moments in their favourite films are accompanied by memorable pieces of voice-over narration.

The young screenwriter starts. They pace around their room. They glare at the computer resting at the other side of the room. ‘But why?’ they scream. ‘Why one rule for them and a different rule for us?’

Rest assured; this article will not discourage the use of voice-over narration. Instead, it will draw attention to the inherent dangers of voice-over narration.

It will also emphasise and explain the need for care when writing voice-over. But it will then highlight great examples of voice-over narration in order to demonstrate the technique’s brilliant potential.

Voice-Over Narration—Why is it Dangerous?

Screenwriting manuals tend to compare movie voice-over to bad eggs. They assure readers that it will make their screenplays stink. They declare it must be avoided.

The screenwriting gurus have a point. Movie voice-overs certainly can reek like a bad egg.

- The problem is that voice-over narration is a classic trap for telling rather than showing.

- With voice-over narration, someone is telling us, as an audience, pieces of information that we could be seeing. This is the fundamental problem.

Too often, screenwriters use voice-over as a kind of exposition. They see voice-over as an easy way to convey necessary information. This is generally the wrong way to approach the use of voice over.

Great movie voice-over narration shows as it tells.

- The voice-over does not merely tell us details that we need to know about the plot.

- Instead, the voice-over reveals something about the story or character beyond what is said.

- The best voice-overs never just offer expository information. They do something more.

Voice-overs should never be used to get out of screenwriting holes. Nor should they be used in times of desperation. Instead, they are effective when the story demands a voice-over.

A good voice-over is always about much more than the information it states. The voice-over has a meaning in and of itself.

5 Times and Ways to Use Voice-Over Narration:

1. The Storyteller and Storytelling

A movie voice-over immediately introduces a storyteller. In doing so, it harks back to mankind’s innate desire to tell, and to listen to, stories.

The concept of a narrator takes us back to the days of sitting around a campfire, where the village poet spun tales while the audience necked mead. Or something like that.

Cinema has, for the most part, put the village poet out of business. We no longer need a single storyteller relaying the story. Instead, we can visually recreate the narrative on a screen.

Having a narrator in a film, then, just in order to tell the story, is pointless. It’s always important to follow the rule of show don’t tell.

Numerous screenwriters, however, include a narrator or storyteller in their films. In order to understand why, let’s focus on Wes Anderson’s movie—The Grand Budapest Hotel.

THE GRAND BUDAPEST HOTEL - Official Wolrdwide Trailer HD

A Triple Narrative

In the opening scene of The Grand Budapest Hotel, a teenage girl visits a graveyard.

- She carries a copy of a book called The Grand Budapest Hotel.

- She then stands before a grave marked only with the word ‘Author’.

- Soon, we hear the ‘Author’ speak in a use of movie voice-over.

- Presumably, this is because the teenage girl is reading his book.

- As she reads, the Author speaks from beyond the grave.

- In the Author’s narrative, he describes meeting a hotel owner called Zero, who told him a story.

- The Author then recounts Zero’s story.

As a result, we have a triple narrative. First, the girl reading the book. Second, the Author’s tale. Third, Zero’s story.

Narration is how we tell stories to people. Anderson mimics this form of discourse in order to comment on the way we tell stories. The layers of narration give the whole film a kind of semi-mythical effect.

Anderson suggests that stories passed from one person to the next lose factual accuracy over time but accumulate a different kind of truth.

- There is something immortal, or lasting, in our shared myths.

- The re-telling of old stories brings not only the stories back to life, but also those that have told these stories.

The Author’s narration in Anderson’s film isn’t there to tell the story. It is there to comment on the way in which we tell stories.

Pastiche and Parody in Voice-Over Narration

The Grand Budapest Hotel is arguably a patchwork of pastiche and parody. And yet the sum of all these copied parts is something entirely original.

The voiceover in the film is just another example of pastiche. The traditional voice of a narrator is aped.

Pastiche

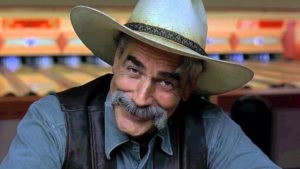

The Coen brothers also use pastiche in The Big Lebowski. Voiceover, delivered by a cowboy-type figure, bookends the film.

This is the opening speech:

Look how great an emphasis this voice-over has on storytelling itself. Each part of the speech is plucked from a tradition of storytelling.

- ‘A way out in the West,’ for example, is how a million stories have started.

- The tone of the writing is conversational. It’s as if this man has just sat down beside us at the bar and begun to speak.

- Note the repetition of ‘fella, fella, fella’. Even the man who delivers the speech, a cowboy, is a Hollywood stock-figure.

What’s amusing about this speech is that it seems to set to be setting up a Western movie. Instead, we’re given a comic crime drama set around Los Angeles. This is, in many ways, a movie about the movies and about narrative itself.

The use of voice-over is a form of pastiche. It mimics what has come before in order to create something different.

- The Coen brothers don’t use the voice-over to convey the plot, they use the voice-over to laugh at the long-standing use of voice-over throughout cinema.

- The voice-over comments on the much longer oral tradition of telling and re-telling stories.

Parody

Voice-over narration is used to a more parodic effect in Mary Harron’s American Psycho (adapted from Bret Easton Ellis’ novel).

Watch the opening:

Patrick Bateman, the protagonist, speaks like a television advertisement.

- Harron implies that Bateman’s ‘self’ has been lost to mass media and modern marketing.

- The director, like the author before her, suggests that in a world of developed capitalism, we gain material products (‘a deep pore cleanser lotion’ or a ‘water activated gel cleanser’) but we lose a soul.

It is entirely appropriate, therefore, that Harron uses movie voice-over.

- Her character draws from, and parodies, mass media.

- Bateman is a comment on high capitalism.

- Harron has him speak in voice-over, not so much to convey the information he offers but to ensure he sounds like a hollow echo of an advert.

Bateman is an empty husk of a human being—just another product in a capitalist market.

2. Adaptation and Voice-Over Narration

Very often, screenwriters will use voice-over if they are adapting a film from a novel (or another literary source).

American Psycho is an example of an adaptation done successfully. Screenwriters do this because they feel the words themselves do something more, or something other, than merely re-tell the story.

Obviously, words in a novel often have a significance beyond their literal meaning. They can hold a particular beauty.

While screenwriters must try to interpret this beauty and reconfigure it visually, sometimes they merely use movie voice-over to resuscitate the writer’s diction.

‘Somewhere Around Barstow’

Take the opening to Terry Gilliam’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas—adapted from Hunter S. Thompson’s novel:

The whole film is littered with similar chunks of narrated text.

- These voice-over passages are lifted straight out of Thompson’s novel.

- This is because Fear and Loathing In Lost Vegas is a novel about writing a novel.

- The construction of the text is one of the events that happen in the text. It is a work of meta-fiction.

- Gilliam’s screenplay is dense with narrated sections because this is a film about a writer writing. Again, voice-over draws attention to the art of storytelling and the role of the storyteller.

It also, however, allows viewers to sample the author’s impressive and distinctive prose. Thompson’s novels hold a strange literary beauty. Replicating passages reveals Thompson’s writing voice.

- Fragments of the novel scattered in voice-over through the film suggest that it isn’t possible to paraphrase literature.

- Sometimes the author’s words must speak for themselves.

- Gilliam implies that, at times, it is impossible to turn a beautiful sentence into a visual scene.

In general, however, a screenwriter should not try to compete with the original work of art. They should try to create something new.

If you feel like you have to use voice-over to continually quote from the adapted work, then chances are you are not creating something fresh and exciting in its own right.

Be careful and restrained in using movie voice-over when adapting a literary text. Write with your own voice, rather than using the author as a literary crutch.

3. Written Texts and Voice-Over Narration

Voice-over narration often emphasises the words as written. Voice-over narration is not conversation. It is not spontaneous.

To justify voice-over, screenwriters will often situate protagonists as reading or writing a personal written text. This can include:

- A Letter.

- A Notebook.

- Diaries or journals.

A written text offers an insight into the character’s way of thinking.

The inclusion of a written text can also mean a voice-over seems more authentic. It provides a justification for the formal, often literary, way in which voice-over thoughts are presented.

A voice-over will make your film seem more literary. Make sure that you are aware of this. Potentially include a literary form alongside voice-over narration if you are worried about realism.

4. Juxtaposition With Voice-Over Narration

Movie voice-over is often effective when the content on screen is juxtaposed with the spoken words. This immediately offers subtext.

All is not as it seems on screen, or as is said in the voice-over. It creates an, often amusing, sense of irony.

‘Choose Life’

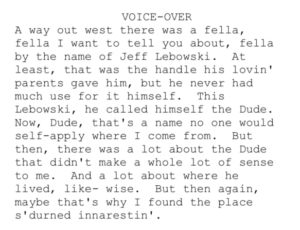

Read the opening to John Hodge’s Trainspotting screenplay here:

Note how the content—Mark and Spud sprinting away from ‘two hard-looking Store Detectives’ jars with the voice-over.

‘Choose life,’ Renton says, ‘choose a job, choose a family.’ The sprinting fugitives look like they’ve selected the very opposite.

- In the voice-over, Renton regurgitates the mundane tropes of a ‘normal’ existence.

- On screen, two men sprint down a road, ostensibly on-the-run from a crime scene.

- Mundane normality clashes with extraordinary behaviour.

Hodge has fun with the audience.

- He knows we don’t want to watch a film about washing machines and televisions.

- We’re drawn away from normality, drawn into a world of excitement.

- This is just as the film’s protagonists, drug addicts in Scotland, forego a life of tedious regularity for the overwhelming ups and devastating lows of heroin.

Comedy

Trainspotting is a black comedy. There is undoubtedly something comic in the film’s juxtaposed opening. This technique is often used in comedy.

Peep Show uses voice-over consistently to great comic effect. In the show, we listen to the thoughts of the two main characters—Mark and Jeremy—via voice-over narration.

Watch this clip:

There is a juxtaposition between Mark’s thoughts and his behaviour.

- Mentally, he acknowledges his own abnormality. He notes the rarity of this kind of evening.

- But, in spoken conversation, he, poorly, pretends that he lives like this all the time.

- The contradiction between the two is amusing.

Using voice-narration to vocalise a character’s thoughts is quite a commonly deployed strategy. It works in comedy because it can often highlight a funny juxtaposition between inner feelings and outer presentation.

It is less commonly used in drama.

- This is partly because it detracts from a film’s realism.

- Obviously, in real life, we don’t hear what a person is thinking.

- We, as viewers, want to work out if there is a gap between what a character thinks and the way in which they behave.

- Using voice-over doesn’t give us the opportunity to do this. It often butchers subtext.

The Uncanny

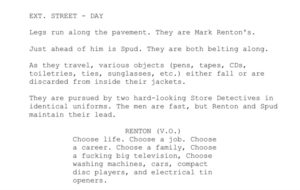

In Yorgos Lanthimos’ The Lobster, juxtaposition is used differently.

- A female speaker narrates sections of Lanthimos’ film in voice-over.

- This is strange because the film’s protagonist is a man.

- We don’t meet this female speaker until about half-way through the film.

The effect ensures audiences constantly question the identity of this unseen female speaker. Who is she and why does she know this man’s story?

Selecting a narrator who isn’t immediately revealed on screen is an effective way of making voice-over engaging.

As with so much of Lanthimos’ dialogue, the content of the voice-over narration itself is unusual and uncanny. The opening voice-over is the following:

Note how the filmmaker subverts the traditional expectation of a voice-over.

- Rather than striking or poetic, this speech is mundane and bland.

- The child-like, uninspired narration helps contribute to the sterile, repressed atmosphere of the film.

So Lanthimos has an unusual narrator say unusual things. The effect is still comic but in a strange, unsettling way.

5. Voice-Over Narration and Memory

Voice-over narration is often reflective.

- A character tells us their story. They look back on a moment or a time. Or even the whole of their life.

- This is immediately engaging because we wonder why this person wants us to know their story.

- We know something must have happened for them to need to tell us their story.

Having somebody tell the story as if it is a memory also gives the narrative the semblance of reality. It, falsely, proclaims that this story happened to someone.

It also allows an intriguing ambiguity between the voice in the voice-over (in the present) and the character on-screen in the past despite this being the same person. How has the character changed over time?

Elegy

A character looking back often gives a film an elegiac tone. Narrators are often most effective when reflecting on something that was there once but is no longer.

A great example of this is Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven.

- The film depicts a love triangle (two men who love the same woman) that goes tragically wrong.

- It is narrated, not by any of the three lovers, but by the younger sister of one of the two men—Linda.

Linda is a detached spectator on the love triangle. It is not her who falls in love. And yet, the story is told through her memory.

- Selecting a narrator for a love story that is not one of the participants is an interesting example of juxtaposition.

- It also emphasises the oral tradition of the story. It gives the tale a kind of semi-mythical status.

The whole film is a sun-blazed, dreamy snapshot of a time and place. It is not so much about the relationship between the three lovers, as it is about Linda’s memory of these happy, and then tragic, days.

- Moments of the film are as if glimpsed through rose-tinted spectacles—golden hues in the evening, happy dances around the fire.

Days of Heaven is a film about memory, about looking back. The voice-over, which creates the effect of Linda reflecting and re-telling the story, contributes to this theme.

Irony

The other great thing about using voice-over as a reflection is that it offers a layer of irony.

- The character in the voice-over, because they are situated in the present, knows the events that will happen.

- The character on screen, because they are in the past, doesn’t know what will happen.

- This creates an exhilarating tension.

Alan Ball’s screenplay for American Beauty takes this tension to an extreme. Watch this scene. It is our introduction to the film’s protagonist, Lester Burnham.

The voiceover declares: ‘My name is Lester Burnham. This is my neighbourhood, this is my street, this… is my life. I’m forty-two years old. In less than a year, I’ll be dead. Of course, I don’t know that yet.’

Lester Burnham narrates this plot from beyond the grave. This use of voice-over is actually effective for several reasons:

- First, it’s striking. We don’t expect a narrator to announce that they’re already dead. Audiences relish the trick.

- Second, it’s intriguing. We now know Lester—who lives in mundane, boring suburbia—is going to die. Viewers will want to find how and why this happens. It makes the film immediately compelling.

- Third, it’s somewhat parodic. Just as with American Psycho, we have a protagonist introduce their life like an estate agent showing off a house.

- Fourth, it’s ironic. The irony is that past Lester doesn’t know what present Lester knows. And present Lester knows that past Lester has less than a year to live. There’s something darkly comic in dead Lester introducing us to living Lester’s existence.

The voice-over in Alan Ball’s screenplay does so much more than relay exposition. Write voice-over narration similarly dense in subtext and no one will make you remove it from your work.

Placement of Voice-Over Narration

The position of voice-over narration in a screenplay is also essential to its effectiveness.

You may have noted how, in the vast majority of examples in this article, movie voice-over is used at the start or end of a movie.

- Movie voice-over can be a great way to get us into a story. As with American Beauty or American Psycho it often proves a really exciting way to introduce us to a character’s everyday.

- Or, as with The Big Lebowski or The Grand Budapest Hotel, it is a great way of effectively saying ‘once upon a time’.

It is also often effective at the end of films.

- Although less common, voice-over narration at the end of a movie can effectively tie up a film.

- The final words of Days of Heaven are spoken in voice-over.

Be careful, however, using voice-over throughout the film. It’s great for bookending the story but it can often interrupt the narrative flow if spaced throughout the film.

This is not, however, unequivocally true. As with all screenwriting ‘rules’, there are many exceptions.

In Taxi Driver, for example, fragments of voice-over narration actually drive the plot forward.

- Travis narrates sections of his diary over shots of decrepit New York streets.

- We sympathise with Travis’ frustration. At the same time, his voice-over gives a window into his fractured mind.

- The voice-over charts Travis’ increasing frustration and drives the plot forward.

In Conclusion – Words, Words, Words

It is essential that voice-over narration does something other than just offer expository information. It must have subtext.

But is also absolutely vital that the spoken words in voice-over narration are engaging and compelling.

The words are more important in a voice-over than in any other spoken section of the film. It must be your very best writing.

- With voice-over narration, there is no actor speaking on screen to hide behind.

- The words themselves are isolated and detached from a speaker.

- Consequently, they have a particular resonance. This is why they are often so popular and so memorable.

Trainspotting’s ‘choose life’ voice-over introduction has been reprinted on posters, t-shirts and mugs. Thousands of film fanatics know Patrick Bateman’s morning routine off by heart. Members in online forums quote Peep Show endlessly.

If the words are linguistically engaging, creative, and exciting then the movie voice-over has the potential to be the highlight of any film. So often, however, voice-overs are the opposite. They feel like lines of transparent expository prose.

Choose originality, choose irony, choose subtext.

- What did you think of this article? Share It, Like It, give it a rating, and let us know your thoughts in the comments box further down…

- Struggling with a script or book? Story analysis is what we do, all day, every day… check out our range of script coverage services for writers & filmmakers.

This article was written by Charles Macpherson and edited by IS Staff.

Get *ALL* our FREE Resources

Tackle the trickiest areas of screenwriting with our exclusive eBooks. Get all our FREE resources when you join 60,000 filmmakers on our mailing list!

Want to go see the first movie. It seems interesting with all the voice overs. Seems like maybe entertaining. Came here to find out what a voice over entailed.

Is it appropriate to use voice over narration alongside a screen description or even a montage? I am writing an adaptation of a story written in the epistolary style, and I’d like to use some of the text from the “letters,” as it’s very beautiful prose. I thought it would be good to use VO narration along with action on-screen to illustrate?

Yes, absolutely – voice over narration with montage is a time-honoured cinematic tradition. It can be particularly useful in period pieces where, for example, two characters are writing to each other, as time passes.

Some of the best films have used voice over. It depends on the type of story and what tools it requires.

If a story depends on voice over and some do, then it should be used but used sparingly. There is no right or wrong as such, it just depends on what kind of story you are trying to convey. Film is a combination of words and images. Not one or other. So I don’t necessarily agree here but I do agree that as much as possible you should show and not tell but it’s a balance.

Agreed, Chris. It’s a fine line. It can work spectacularly, and equally it can feel incredibly lazy and derivative and copycat-y. Like so many other aspects of screenwriting and filmmaking it is the embodiment of “execution dependent”…

The final point is key – the spoken words must be compelling. This is the job of the narrator. A narrator cannot make every piece of text sound great, but must try to do so nonetheless. If the words are not brought to life in a specific way, they can lose all meaning.