No matter what part of the filmmaking process your job role fits within, there’ll likely be a time when you’ll be expected to give script notes on a project.

1. Don’t Be Personal

This is important when giving any kind of script feedback or professional advice. You have to take yourself out of it as much as possible.

Being objective is essential. And this will be acutely reflected in the language you use. Avoid too much use of the first person (I) and instead, try and use more third-person descriptors. Refer to the script as a collective goal to be improving on. Don’t create barriers between you and the writer. You create barriers by framing your script notes firmly on your own side, with the writer on the other.

Instead, place yourself on the writer’s side by taking yourself out of the equation. The script is an object that you’re both seeking to improve. It’s not an opportunity for you to tear down a script by flexing your hallowed opinion.

2. Highlight the Positives

Whether you’re giving your script notes in prose form or within the script itself (in the margins), it’s important to frame your feedback from a positive angle. Even if you have mostly negative feedback to give, you should be focusing on the end goal of improving the script.

Focus on how close the writer is to their goals, rather than how far away they may be. You need to imbue the sense that the writer will burst through to the other side soon enough. Otherwise, the writer may feel it is too much of a mountain to climb. They, therefore, may procrastinate and delay the improvements.

3. Focus on Character Arcs and Consistency

How do the character arcs track across the length of the script?

When giving script notes, you don’t want to focus too heavily on whether a character does or doesn’t work overall. Instead, you want to focus on how tangible and effective their characterisation feels.

- Does the character feel that they could be more empathetic?

- Could their goal be more acutely clear?

There’s no point in making the writer feel hopeless about the character they’ve invented, whether it’s the protagonist or a supporting character. Instead, if there’s criticism, you want to try and get across that the character is someone who you get a hint of but would like to know better.

4. Don’t Take Down the Key Premise, Focus on Articulation

Similarly, there’s little purpose in making the writer feel hopeless about their story concept or premise. If the script is ready for production, there’s no point in destroying the premise. But all the same, if the script is just getting off the ground, there’s no point in making the writer feel like they should raze it all to the ground.

So instead, your script notes should be focused on how clear and articulate the script’s central premise is.

- Does the story feel like it’s about one thing, only for this to become increasingly unclear?

- Or is it hard to get a feel for what the story is about at all?

Try and understand the writer’s key vision for the story. Focusing on where this vision is unclear is a good way to encourage the writer to better articulate what they’re going for. Often there’s a mismatch between a creative vision and the execution. And your job in giving notes should be to help the writer bridge this gap.

5. Does it Live up to its Genre?

This also applies to the genre. Does the script match the genre it states it is? Is there enough tension for a thriller? Enough emotion for a drama? Enough set pieces for action?

You don’t want to be too prescriptive when it comes to making sure that the script ticks all the boxes in regards to its genre. Often the best scripts subvert genre after all. However, the writer may well have strayed off track when it comes to maintaining the rules of the specific genre they’re writing within.

Does the script really feel like the genre it says it is? This is always a good check to hold the script up to. But again, it’s shouldn’t be about holding the script up to a certain standard and criticising it for failing to meet that standard. Instead, the script notes should seek to help the script match its goals and ambitions.

6. Question Dialogue Effectiveness

Dialogue feels like an easy technical element to critique and write notes on. It’s often one of the elements that is most noticeable if poorly done, both within a script and on-screen.

However, rather than just seeking to tear the dialogue down if you think it’s no good, question how effective it is at articulating the story, characterisation and themes.

- Could the dialogue be pared down?

- Could there be more dialogue?

- Is it a case of the dialogue needing to be more incisive?

If you start taking chunks of dialogue away without asking, for example, the writer may feel they are losing control over their script.

So instead, make points and suggestions. And always remind that dialogue is an essential part of the storytelling, not a stylistic element or accoutrement.

7. Offer Solutions and Pose Questions

This is key to any kind of writing. If you’re going to make points, you have to back them up with examples. And if you’re going to point out flaws or problems, you have to offer solutions as a countenance.

The best way to do this is to encourage the writer’s imagination. Open them up to possibilities by asking questions. Whilst you want to avoid making too many specific, instructive recommendations you can point the writer in the direction you think might be helpful. And you can do this by posing questions and encouraging them to think about what the answers might be.

You don’t want to make the writer feel hopeless with your script notes. Instead, you want to create the tangible idea that whilst there may be issues, there are clear ways to remedy them.

8. Lean into Your Role

What is your role within the production? Producer, development executive, cinematographer, assistant director? A great way to ensure that your script notes are actionable and useful is to make sure they pertain to the role you have in relation to the script.

For a cinematographer, for example, this might mean paying attention to the practicalities of realising the visuals of a scene. A producer, meanwhile, might focus on the broader aspects of marketability or the practicalities of production.

You will likely have been asked to provide notes for a specific reason. So make sure this reason holds true within your notes, leaning into what you have to offer the script in terms of your professional advice.

9. Find and Use References

References are always valuable for the writer receiving script notes. For a screenwriter, it can sometimes be tricky to envision how their script is seen. And providing acute references can help in doing this.

- Does the screenplay remind you of a TV show or film?

- Which films or TV shows might be useful for the writer to watch in order to better a specific part of the script?

These references can be anchors for the writer to latch onto. They’re ways of envisioning their script in its potential form on-screen. And this is a positive way to give notes. It lights the writer’s imagination and showing their work in the context of other, fully-realised works.

10. Be Specific About Scenes, not Broad in Your Takedown

Finally, try and be as specific as you can when giving script notes. It can be tempting to reach for overarching statements about the script you’ve just read.

However, it’s important to remember that giving script notes is distinct from just giving thoughts and opinions on something you’ve just watched on TV or in the cinema. Your script notes typically will exist to improve on the script, not just provide a summation or general impression of it.

So be as specific as you can about how and where to improve the script. Focus on where and how to rewrite scenes in particular, rather than on broad story movements. How does each scene help or hinder the overall picture? Moreover, what are the details of each scene that work or don’t work?

Only with specific, tailored and close advice will the script improve and will your script notes be worthwhile to the screenwriter.

10 Script Notes to Avoid

One of the most important skills a writer can develop is knowing when script notes are utterly valid, justifiable – necessary even – and when they’re not.

It’s a skilful dance between protecting and preserving a vision and making necessary enhancements.

For a writer, the best way of approaching inferior script notes is to look for the note behind the note…

So when giving notes, there are certainly script notes that should be avoided. These are the kind of notes likely to annoy a writer. And you want to make sure the writers react to your feedback positively, even if the work ahead may be long and arduous.

1. “The protagonist needs to be more ‘likeable’…”

A perennial favourite of anyone who’s ever come across a screenwriting book of any kind, this note falls apart under the slightest scrutiny. Since THE SOPRANOS and BREAKING BAD, anti-heroes and prestige TV have gone hand in hand.

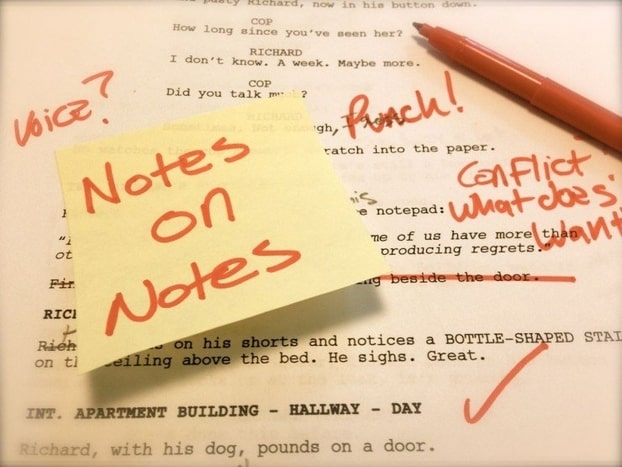

Craig Mazin, award winning film and television writer, touches on this note in a related episode of the Scriptnotes podcast titled Notes on Notes.

“The issue is how do you find a way to make that person’s unlikeableness relatable. Relatable is not likeable. Relatable means that I understand it.” – Craig Mazin

Scriptnotes co-host, John August, adds to this by suggesting to rephrase the note as a “disconnect to the character”. There’s a difference between likeability and being understandable, between sympathy and empathy.

- If a protagonist is understandable in their goals and motivations, even while doing bad, unsympathetic things, it goes a long way to overcome the problem of being unlikeable.

- It also involves the audience in a moral conflict, whether to root for their redemption or not.

2. “Don’t leave the ending up for debate…you’re not writing a franchise!”

The denouement, those scenes after the climax, go a long way towards shaping the audience’s perception of a film.

For example, it’s traditional in the horror genre to have the killer or monster come back or disappear at the end, even if it’s not for franchise reasons.

But beyond horror, THE SILENCE OF THE LAMBS and INCEPTION show how unresolved plot threads can provoke the audience’s imagination and cause debate.

3. “It wouldn’t happen this way in real life.”

Movie logic is different from real world logic. If films had to follow reality, they would be dull. For one, this would eliminate the superhero genre.

One of the purposes of storytelling is to experience something that’s out of the ordinary. Audiences are willing to suspend their disbelief.

However, the story has to be internally consistent and believable, or the audience will be taken out of the film. The audience needs to believe that it is happening within the story world that screenwriters create.

4. “This scene is too melodramatic.”

Too often, writers who are afraid of melodrama shy away from giving characters strong emotions. There are better ways to write this note. There could well be a disparity between the characters’ level of emotion in this scene and their motivations leading up to it.

The tone and the genre might have been uneven scene to scene, and as a result the screenplay hasn’t created the right expectations to support melodrama. Often this note refers to a symptom and the cause, the real problem, lies elsewhere.

5. “Never use camera directions or ‘we see’.”

Like voiceover or flashbacks, camera directions and “we see” have been overused so much that some maintain an outright ban.

On the one hand, it’s not the job of the writer to direct on the page. On the other, the ultimate aim for screenwriters should always be to write something that’s engaging and easy to read and visualise. As with any technique, when camera directions and “we see” are used sparingly and purposefully they can help achieve this.

6. “This idea’s been done before.”

Notes like this forget how far the sentiment of this script note could date back to.

Other public domain classics such as the works of Shakespeare are re-imagined year after year. Directors like Quentin Tarantino also liberally borrow from and pay homage to their favourite films.

This note is more of an observation than a useful criticism. A more productive way of looking at this issue is to ask whether, if the screenplay does make use of familiar material, it has done so with a fresh perspective.

7. “Don’t let the audience get ahead of the characters.”

There’s a knee-jerk reaction that if the audience can figure something out earlier than the characters this will inevitably result in boredom.

Again, this is genre and story-dependent rather than working as blanket advice. A murder mystery, for example, is definitely weakened if the audience find the solution before the characters.

In a thriller however, Hitchcock’s definition of suspense applies. If characters are shown sat around a table talking and suddenly a bomb goes off, that’s merely surprise. However, if the audience know there’s a bomb under the table, and see it counting down while the unaware characters sit around talking, that creates suspense.

This sense of anticipation, of dramatic irony, is also what makes films worth re-watching. Whether the audience are supposed to know the same, more or less than the characters, it’s more important to be in control of the flow of information.

8. “The inciting incident has to happen as early as possible.”

One of those script notes that generally holds to be true, although the caveat “as possible” is vital.

ROCKY, for example, is a film that spends a great deal of time establishing the characters before they are upended by the inciting incident, when Apollo Creed chooses Rocky as an opponent.

- It’s only because the audience have experienced Rocky’s down-and-out everyday existence that it’s clear how one-sided this fight will be.

- Rocky has also been established as someone with nothing to lose but his self-respect. The audience understand how he doesn’t want to win but that just going all 15 rounds will be a personal victory.

9. “The protagonist has to be active and not reactive.”

There’s a difference between a reactive protagonist and a passive one. Too often, the terms are confused.

Often, especially at the start of the story, the protagonist isn’t in control of their situation. They are reactive but not necessarily passive. They can still have a goal and they still make decisions. This allows for the protagonist to undergo an arc, to go from reactive to proactive.

10. “The protagonist has to have an arc.”

While character arcs are beneficial for so many stories, the exceptions are notable enough to think twice about this kind of feedback.

On rare occasions, the fact that the protagonist doesn’t change is what leads them to victory (or dooms them to failure). They are tested and their existing strength – morally, physically – proves to be enough. Whether they’ve changed internally is up for debate.

For example, Indiana Jones arguably doesn’t change over the course of RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK. The sequels all added in character development and arcs, to varying success.

–What did you think of this article? Share It, Like It, give it a rating, and let us know your thoughts in the comments box further down…

– Struggling with a script or book? Story analysis is what we do, all day, every day… check out our range of script coverage services for writers & filmmakers.

Get *ALL* our FREE Resources

Tackle the trickiest areas of screenwriting with our exclusive eBooks. Get all our FREE resources when you join 60,000 filmmakers on our mailing list!

Good to know. I’ve had many of these notes.

With all due respect, your #1 on this list isn’t something that really happens.

1. “The protagonist needs to be more ‘likeable’…”

“…So many classic protagonists are in fact anti-heroes. Is TAXI DRIVER’s Travis Bickle likeable when he plans to assassinate a politician?” [Actually, yes! He is!] “Or Michael Corleone in THE GODFATHER when he decides to continue his father’s criminal legacy?” [YES!!! He’s highly relatable and charismatic!!]

You and your readers need to understand that when a script reviewer –of any competence– says the protag needs to be more likable, it’s not the same at all as having a moral problem with the character’s actions. It almost always means the character is simply irritating, shallow, or otherwise unsympathetically presented.

Over the years I’ve participated in (and taught) several writing workshops from graduate level down to college first-years, and I have only once ever seen a student critic confused in the way you’re describing — a student who was bewildered in general by the course and its reason for being.