Table of Contents

- How Do Filmmakers Approach a Script?

- Steven Spielberg: Getting Personal

- Jane Campion: Creating Female Stories from the Source

- Kenneth Lonergan: That Which Is Left Unsaid

- Dee Rees: Character is Key

- Céline Sciamma: Balancing Desires

- Paul Thomas Anderson: Visual Emotions

- Ryan Coogler: The Power of Intention and Voice

- Alfred Hitchcock: Less Talk, More Action

- David Fincher: Following Characters

- In Conclusion

How Do Filmmakers Approach a Script?

The screenplay is the spine of the movie. But the way it is interpreted for the screen is the key to turning a great script into a great film (or piece of television). Whether they be writer-directors or directors alone, the filmmakers who can get the most out of their scripts often end up making some of the most compelling films out there.

A motion picture isn’t just a copy-and-paste of the screenplay it’s derived from. In between, there is a period of interpretation in which the story comes to life in the most important ways. It is the job of filmmakers, at that point, to ensure that the story is understood. Only then can they share this understanding with their crew, and then the audience.

Now to “get the best out of a script” looks different from filmmaker to filmmaker. It could be their mastery of theme, character, tone, or all of the above. It is a vague concept. The point is that these filmmakers can capture the most important qualities of a story and communicate them effectively.

It would be impossible to name or make a list of every filmmaker who is skilled at efficiently milking a script. Here are just a few filmmakers you likely know of and how they get the most out of a script in their own inimitable ways.

Steven Spielberg: Getting Personal

Spielberg is a filmmaker famed for keeping audience members on the edge of their seats with tension. More underrated, though, is his skill at telling stories that are deeply personal to him.

The theme often in question is the experience of being a child of divorce.

First, consider Close Encounters of the Third Kind, which Spielberg co-wrote. Protagonist Roy Neary leaves his family behind, drawn by the allure of a mysterious alien presence.

- Spielberg’s storytelling here pulls the audience in two different directions.

- On one hand, Roy is the main character and therefore we, as the audience, want his wants.

- On the other hand, we feel the pain that his wife and children experience as he slips away from them.

- It makes the audience feel guilty for rooting for Roy, therefore rooting against Spielberg.

Spielberg’s ability to extract those emotional undertones that are secondary to the main storyline is indicative of his skill at inserting himself into the scripts he directs.

Next, take E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial. Elliot’s parents have just divorced and his father is out of the picture – a fact which puts a visible strain on the family. Elliot’s attachment to E.T. is stronger because he is experiencing the pain of abandonment.

Though Spielberg didn’t write this film (Melissa Mathison did) – it feels personal to him. His strong personal connection enables him to insert himself into the story. When the story feels real to the filmmaker, it will, in turn, feel real to the audience.

What makes Spielberg such a brilliant filmmaker is not just his talent for making entertaining, high-stakes Hollywood blockbusters. It’s the way he finds himself in the screenplay, and therefore makes characters he didn’t even create feel more three-dimensional. Spielberg demonstrates how filmmakers can make the personal universal.

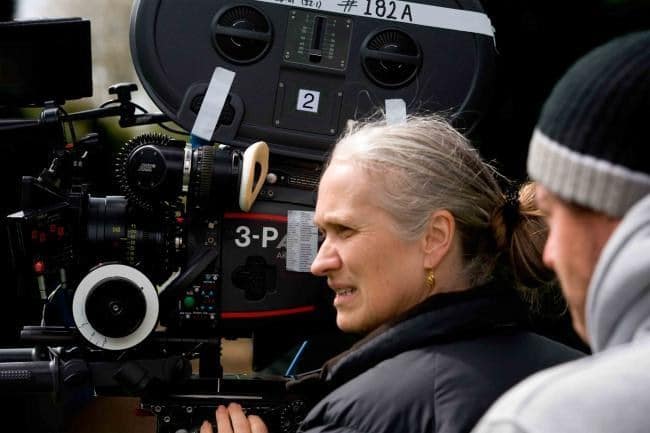

Jane Campion: Creating Female Stories from the Source

Campion has spent her career telling stories about layered, troubled, yet strong women. Her work demonstrates how giving women control of female-driven stories enriches their narratives and the portrayal of the female experience.

Film theorists like Laura Mulvey have long discussed the male gaze that pervades any film with a female character portrayed in an even remotely sexual light. Jane Campion subverts this gaze as a filmmaker, giving the woman power over it. She gets to the core of her characters and realizes them in striking, unglamorous clarity.

The Piano is an impressive display of her work because of one particular challenge: a mute protagonist. With only Ada’s body language (and occasional interpretation offered by her daughter) to tell us anything about her, it’s Campion’s clever character development that makes the movie.

- On paper, as a 19th-century woman who can’t speak, Ada may seem vulnerable and weak.

- But Campion paints her as being persistent, determined, and powerful, all while being silent.

- A complex approach to a complex experience that could only truly be accomplished so well by a female filmmaker.

In the Cut is another film in which Campion exerts the female character’s strong will.

- The sexual power she grants her protagonist may be jarring to viewers who are used to male-crafted narratives.

- But Campion handles female sexuality with control and purpose.

- She challenges the idea that women and eroticism can only mix when paired with Hollywood’s flowery understanding of romance.

Campion is an expert at portraying the intricacies of desire. She not only gives the women in her films power; she gives them layers. Campion’s work gives us permission to appreciate flawed female characters like we do male ones. And she shows us exactly what they look like.

Kenneth Lonergan: That Which Is Left Unsaid

Emotion starts with character. Filmmaker Kenneth Lonergan’s mastery of deeply complicated characters is hugely responsible for making his tragic, moving stories so impactful. Perhaps the most powerful quality of his work, both as a writer and a director, is found in what is not explicitly said.

Manchester By the Sea earned Lonergan the Best Original Screenplay award at the 2017 Academy Awards, and for good reason. It’s the simplicity of the script that’s so memorable. Often the dialogue is minimal, particularly that of his main character, Lee Chandler.

To accomplish the essence of a character with less dialogue on the page can be trying for a filmmaker. Often one finds the cadence of a character in their choice of words. Lonergan has “show, don’t tell” down to a T. He tells us as much about Lee as he can by having Lee say as little as possible.

Actions speak louder than words. We consider this to be true of people in our lives, and yet we expect it less in the media we consume. Lonergan shows us the communicative power of actions by giving us Lee’s anguish in his quietness, his restraint in triggering moments, and the pain visible in the very way he carries himself.

From the dialogue he crafts to the performances he guides, Lonergan demonstrates the value in filmmakers leaving things unsaid. In doing so, he also shows how full of information those empty spaces are.

Dee Rees: Character is Key

The most important thing a filmmaker can pull from a script to create a compelling story is character. Dee Rees makes a splash with her films specifically on account of her rich character development and mastery of believable conversations.

Character begins on the page. However, dialogue should never feel like it’s coming from a page. Writing dialogue that doesn’t feel like dialogue is one thing. Directing it to not feel like dialogue can be a challenge. Rees’ characters on screen always speak with the effortlessness of real people.

As far as her directing goes, intentionality is the key. It’s not just about getting a variety of shots just for the sake of it. Rees uses the camera to capture the story in the most impactful way. She situates her actors in the frame according to their characters’ relationships and the tensions the scenes require of them.

The shots aren’t the center of attention, the story is. The camera is just there to capture the story and supplement it when needed. The result is that the characters take center stage. And given Rees’ mastery of crafting compelling characters, her intentionality allows her to tell her audience exactly what they need to know about her characters.

What’s impressive about Rees’ films is that she does not make herself a part of the film. She is a selfless filmmaker, not using her craft to fuel her creative ego. Her focus remains instead on the story she is telling and removing her persona altogether. Everything she does is in service of the story, which is the biggest favor filmmakers can do for a script.

Céline Sciamma: Balancing Desires

French filmmaker Céline Sciamma herself has spoken at length about the role that desire plays in her work, both thematically in her stories and technically in her creative process.

Sciamma’s work reflects a dedication to what lies at the heart of her stories. In most cases, desire as a concept is the very thing she is working to deconstruct, understand, and reconstruct in a way that tells us about the story.

Her film, Portrait of a Lady on Fire, divulges in romantic desire. But given that it is a period piece about a lesbian relationship, those desires are externally and internally limited. Sciamma demonstrates to us what desires can and cannot be acted on, and how her characters navigate this.

Sciamma has spoken freely about her process as a screenwriter. One of the things she emphasizes is the process of training her own desires. Separating the things a screenwriter wants to put into their story from what their story needs, and finding ways to blend them, is a key component of making a beautiful and compelling film.

When a scene is only there because it seems logical for such a scene to progress the story forward, it’s easy to lose the heart of the story in the logistics. Hence the importance of the blend between a screenwriter‘s desire and realistic needs. Sciamma has a strong hold on this concept.

Many moments and details in her scenes can seem more for show. She steers past this, however, by giving them a significance that connects them to the story.

In Sciamma’s screenplays, a great deal is not articulated. She leaves many words and intentions unsaid. In place of them, she leaves space for us to feel her characters’ desires, and demonstrates their grasp on their desires through their actions.

Paul Thomas Anderson: Visual Emotions

Though the story is the make-or-break point of any film, visual storytelling goes a long way in contributing to and enhancing the story. Paul Thomas Anderson’s style of filmmaking demonstrates what it means to have the camera be a storyteller of its own.

The shots filmmakers use during a scene can deliver a great deal of information that is not explicitly said by the characters. Referring back to the Mike Nichols notion of reading between the lines, P. T. Anderson rather reaches underneath them, pulling out what is unsaid beneath the words he himself wrote.

For instance, in The Master, Anderson’s shots do a great deal of work to expose the emotions of his characters.

- In an interrogation scene, a static shot on protagonist Freddie Quell as he struggles to answer painful, revealing questions about himself forces the audience to sense his emotional struggles.

- These types of shots similarly help us to better understand the insecurity of a power-hungry man in Lancaster Dodd.

- When his authority is being threatened, he is framed from a wider shot to make him appear smaller, or partially obscured by an object or person, demonstrating his compromised position.

Anderson’s shots trap us with the characters. They make us study their faces to see the emotions that reveal the most about them. This is what it means for a film to reveal what lies underneath the script. The inner workings of these characters lie at the story’s foundation.

This approach is a textbook example of filmmakers using emotional symbolism and purposeful camera work in cinema. Which is just the point, really. Anderson’s mastery over style enables him to use it not just for aesthetics, but in a way that reveals more about the story and its characters than anything else could.

Ryan Coogler: The Power of Intention and Voice

For screenwriters and filmmakers, navigating voice is a crucial concept. It’s where they find not just their style, but their authority in telling compelling stories. Coogler first centers his work on themes he’s passionate about. He starts his writing process with seeking topics that matter deeply to him, then builds around that.

Though Fruitvale Station finds its hero in Oscar Grant, it does not do too much work to mask his flaws or to champion his strengths. Rather, Coogler poses Oscar as simply a man going about a day in his life. All to show us what is lost when that man is unjustly racially profiled and killed. That says so much in itself.

Black Panther, on the other hand, has a grand scope and a sweeping message about identity and culture. It does more to speak to an overt powerful message. This is likely in part due to the magnitude of the Marvel name, as well as the more complex themes underlying it.

The commonality between the two films is Coogler’s own voice, and that the person behind that voice is speaking to something he cares deeply about. His ability to approach that in different ways speaks to his versatility.

A filmmaker who begins with themselves and stays true to their voice can tell a whole breadth of different stories. At the end of the day, Coogler’s filmmaking is less about style than it is about topic. Namely, topics of importance to him, which he then makes important to his audience. He knows how to give audiences what they want, while also delivering what he wants them to soak in.

Alfred Hitchcock: Less Talk, More Action

Alfred Hitchcock was transparent about his understanding of the separate, but intertwined responsibilities of the screenwriter and the director.

Hitchcock is in the minority on this list of filmmakers in that he did little to no actual writing on his films. He did, however, work very closely with his writers during the drafting of the scripts. He was specifically deliberate about not using dialogue as a crutch when other visual techniques could deliver information in a more interesting way.

We see a different kind of intentionality here than with Ryan Coogler. It services feelings rather than themes. Where Hitchcock feels the script has done its part, he allows the camera to step in and facilitate tension.

Rear Window might be the best example of this.

- As a film rooted in voyeurism, the script describes visuals more than dialogue.

- Throughout the film, tension is built through the protagonist’s view of the scene out his window.

In fact, everything we initially need to know about the protagonist‘s relevant backstory is told to us through visuals. That he has a broken leg. That he is a photographer who specializes in daring topics. The broken camera we see tells us that these three details are connected to one another.

The story’s tension is most palpable when we are watching the action happen through the protagonist‘s point-of-view. These shots put us in his shoes. We sense his curiosity shift to stress when the woman he loves becomes involved in the suspicious and potentially dangerous scene he is watching. All the while, little to no dialogue is delivered.

This is not to say that the script is useless to visual suspense. Without the script, there would be no foundation for the story. The events we see on screen originated in the script. There are simply things that visuals can do more effectively than words can. That is why filmmaking is such a collaborative medium. Hitchcock’s process reveals where the work of the writer ends and that of the filmmaker begins. After all, a finished script is an unfinished film.

David Fincher: Following Characters

What stands out perhaps the most about David Fincher’s style as a filmmaker is his camera movements and positioning. Fincher uses the camera as a tool through which to follow the characters’ emotions – literally, as oftentimes the camera physically follows the characters in their movements. It’s a form of realism that locks the audience into the character and the story.

This effect puts the audience directly in touch with his characters. When the camera follows a character, we have no choice but to fully focus on them too. We study their movements and their expressions and their energy. It’s an interesting visual response to the cornerstone of storytelling which dictates that everything must come from character.

The Social Network has an auteurist feel to it. Fincher’s filmmaking is like an extension of Aaron Sorkin‘s trademark idiosyncratic writing style. It’s an interesting example of a film that really feels like it belongs to its script, which can be attributed to the way Fincher fuses the camera to the characters.

When the camera attaches itself to Mark Zuckerberg’s movements, the audience becomes acutely aware of his behaviors. This tells us more about him without being overt about it, much in the way we study people in real life.

Fincher’s work demonstrates a real effort to study his stories before making his filming choices. This is especially notable given that he does not write his films. It takes a great deal of preparation ahead of shooting to accomplish what Fincher does through his camera movements. The power of preparation, which starts with a solid script, contributes hugely to his work and his reputation as a film director.

In Conclusion

Filmmakers bring their own unique style to any script. That’s the bottom line. But filmmakers cultivate this unique style by the way in which they approach a script. The filmmakers on this list all have their own way of reading a script and translating it to screen. In many ways, this is the key to their art. It may be a representation of how they see the world at large, it may be the way they view filmmaking and its purpose.

A feature film is the marrying of a script to a visual representation of the words on the page. Therefore, filmmakers must find their own way of bringing out what lies both on the surface of a script and in between the lines. A film director will seek to interpret the language of the script in their own voice and with their own intentions.

For screenwriters, this means making that language as clear as possible. Could a filmmaker bring their own style to your script? Is there enough room and enough depth within your script for filmmakers to both elevate it and bring their own voice?

Whether they are filmmakers working on their own scripts, or filmmakers working on another writer’s script, more than anything the above list reminds of how much filmmaking is a collaborative medium.

This article was written by Ariana Skeeland and edited by IS Staff.

– What did you think of this article? Share It, Like It, give it a rating, and let us know your thoughts in the comments box further down…

– Struggling with a script or book? Story analysis is what we do, all day, every day… check out our range of script coverage services for writers & filmmakers.

Get *ALL* our FREE Resources

Tackle the trickiest areas of screenwriting with our exclusive eBooks. Get all our FREE resources when you join 60,000 filmmakers on our mailing list!