When it comes to narrative pacing, we all know the feeling of being on the edge of our seats, biting our nails with anticipation for what’s to come.

What is Narrative Pacing?

Narrative pacing refers to the speed that the events in a story are told. To put it most simply, this means how quickly or slowly the action unfolds.

Pacing has a significant impact on how an audience enjoys and engages with your work. Good pacing will keep them involved and connected to your characters and events. It will make the action feel natural and have the intended effect in terms of the tone conveyed.

Overall, narrative pacing…

- Controls the narrative flow.

- Can be used to manipulate how much information is revealed to the audience and when.

- Affects the mood of the story and impacts the emotional response.

- Helps develop and interweave themes and ideas.

- Can be used to build suspense and tension

Why is Narrative Pacing Important?

A successful narrative needs to flow. Without correct and consistent pacing, your screenplay may feel disjointed. So narrative pacing is vital to keep the story moving and the audience following along. It’s a way of controlling the audience’s engagement and response to the action.

For example, if the narrative pacing is…

- Too fast – it risks rushing through events and overwhelming the audience.

- Too slow – it risks boring your audience.

- Too much of the same – it will start to feel frustrating and potentially tedious.

A good narrative pace keeps the audience actively engaged, unthinkingly.

Meanwhile, bad narrative pacing risks breaking the suspension of disbelief. This is usually due to the narrative starting to come off as too contrived. This will draw the audience out of the story and make it far more challenging for the screenwriter to bring them back in again.

Reasons for poor pacing may include…

- Unnecessary scenes.

- Overly extended scenes or scenes that are too short.

- Uneven rising and falling action.

- Clunky dialogue; eg. length of sentences, word choice and order.

Rising And Falling Action

In some scenes, the pacing demands to be slower. For example, the fallout of a high-stakes scene calls for a reflective moment. This is an important time to slow down, allowing the characters and audience space to breathe.

In other instances, your pace will be faster, such as during an action sequence, or in the moments when you’re hurtling towards the climax of the story. This takes the gradually increased tension, heightens the anticipation of its release, and creates excitement.

- Rising action is the building of conflict and tension. It leads us to the climax of the story, hooks the reader and keeps the anticipation high.

- Falling action, meanwhile, is the tension stemming from the central conflict, which decreases and eventually resolves.

They demand a balance of tempos, with slower and faster-paced sections flowing seamlessly and consistently. Achieving the balance of rise and fall will be the main factor in keeping your audience’s attention. Overall, it’s important to avoid having too much of one or the other.

- For example, audiences will find too much rise and a constant fast pace overwhelming, perhaps even frustrating, if the narrative is continuously building up to something but never provides any release.

- Equally, if there is too much falling action and the anticipation never quite reaches what’s been promised, the story may feel anti-climatic.

Laying the Foundations for Good Narrative Pace

There are numerous ways to control your story’s pace; from the lengths of your scenes, to the amount of dialogue, or even the use of devices such as subplots.

Let’s look at several tips, reminders and examples to set you on the right track. How do you start to make sure your pacing is under control?

1. Scene Breakdowns

It’s good practice during the planning stage to write scene breakdowns. This can be a detailed paragraph, or you can treat it more like a logline for each scene.

When doing this, you could note down, even as short bullet points, where the rising and/or falling action occurs. This should give you a clearer view of each scene individually and an initial indication of how to approach pacing.

Then consider the story as a whole.

- How is each scene working in relation to the other (eg. setting up action for the next scene or resolving conflict from the previous one)?

- Where are the rising/falling events primarily taking place?

- Are these flowing seamlessly throughout?

- Is there a good balance of narrative pace?

One way you could envision this is as a graph.

For each scene, determine how high on a scale your rise event is, and how low your fall is. Obviously, the higher, the riskier the stakes. The lower, the less conflict.

Chart them on a graph and then draw a line connecting the dots. This can give you a visual understanding of how the rise and fall is happening throughout your script.

- What should become apparent through this is any unbalanced pacing and where it occurs.

- If there’s too much rise or fall, especially for a long period of time, reconsider how and where these events occur.

- There is always the opportunity to experiment and change when the scenes happen, but it’s better to identify this early on in the planning stage or after a first draft.

Ultimately, the narrative pacing will always benefit from balance and variety. And laying it out in front of you will help envision where this variety does or doesn’t occur.

2. Genre

Whilst you can use all sorts of techniques to control narrative pacing, it probably won’t have the desired impact if you don’t bear in mind the genre you’re writing in.

Thrillers, for instance, typically have a slow-burn build, but can become fast-paced and action-packed. A thriller will almost always have high stakes, so it can’t just move at a crawl throughout.

Silence of the Lambs is an example of a psychological thriller that expertly nails pacing.

It spends a lot of time with the characters, digging deep into their psyches. This gives the audience the feeling of being very present and involved. It builds the tension by allowing the audience a window into the character’s backstories, state of mind and unpredictability.

Moreover, the film’s dialogue is unsettling. It contributes to ensuring the general mood remains disturbing throughout. There are many lingering close-ups and actors speaking almost directly into the camera – staring straight at the audience.

As a whole, Silence of the Lambs masterfully manipulates pace, giving the perception of moving slowly, but never once flagging. It’s constantly building to its eventual release, doing so with an abundance of atmosphere.

3. Holding Back

Revealing information selectively is another important technique in writing. Such reveals can be used instead of relying on information and exposition dumps – two things which will undoubtedly cause your narrative pacing to suffer.

- Think creatively about how you can write these reveals.

- Holding back information creates suspense and encourages active spectatorship.

- Furthermore, it enables you to gain greater control over the narrative pacing and thereby your intentions.

- It will hook the reader into wanting to find out more and give them a reason to hold on to the story.

This technique is most noticeable in mystery and suspense stories. Leaving questions to be answered and gradually offering information, whilst keeping the right amount withheld, keeps the audience engaged and wanting to figure out more.

This is a great way to build and, importantly, sustain interest.

A great example of this comes in Knives Out, which is a cleverly plotted story with narrative twists and mysteries to solve.

Plot devices are utilized for reveals. This includes dialogue hinting towards character motivations, following and subverting genre conventions, and flashbacks to show what each person was doing the night of the murder. Most notably, Knives Out has twists that tell the story, rather than being there for shock value.

Staying true to the constant unfolding of the story is a key way of keeping order over the pacing. It maintains a focus, holding back information but continually revealing more, therefore, always keeping the story moving and the pace continual.

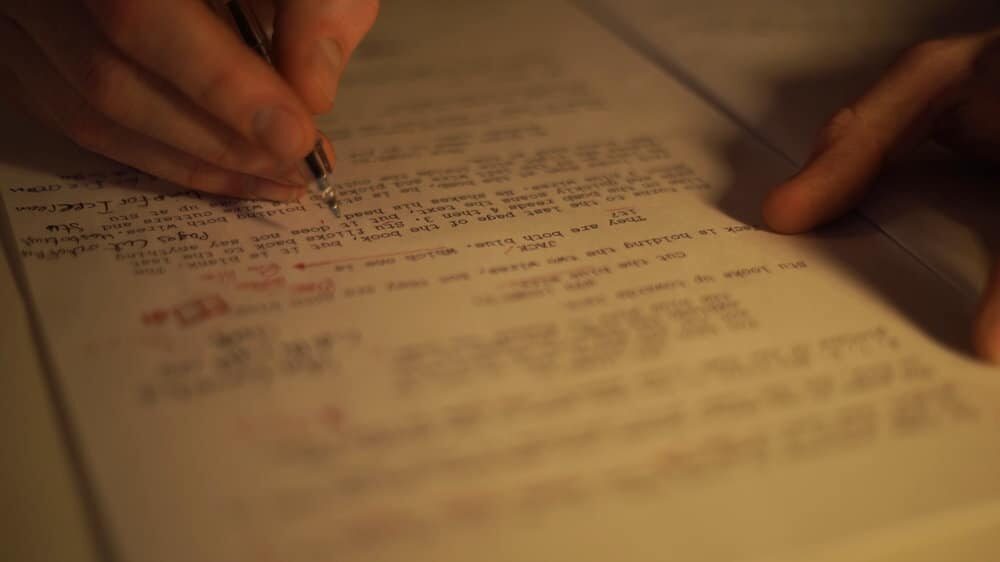

4. Reading Out Loud

This might seem like an obvious piece of advice, but it’s essential in helping you manage your pacing.

Read your work out loud. Either with yourself or other people. You could even set a timer for each scene and note down how long it takes you to read through. This will help you get a feel for the natural rhythms, especially when it comes to notorious trip-ups like dialogue.

Dialogue can be tricky to navigate for many writers and it’s often one of the biggest causes of pacing issues. If your sentences feel clunky or challenging to read, perhaps reconsider the word order. Sometimes that’s all it needs to feel more natural, or cutting any unnecessary words and large chunks out.

Another reason to read through your work out loud is that it’ll allow you to naturally recognize where you might need to pause, slow down or gain some momentum.

This won’t just improve your work in terms of narrative pacing, but your writing and screenplay, in general, will greatly benefit. It can be easy to forget that your writing is ultimately meant to be read aloud. And doing so early on will help you in sharpening the flow and feel of your work.

5. Being Ruthless

Ultimately, you need to be able to strip your story down to its essence. Ask yourself what has to be included and what doesn’t.

- Look at your scene breakdowns. Is every scene completely necessary?

- Ask yourself whether it contributes to the plot.

- Most specifically, does it progress the narrative forwards?

- Is it providing essential character development?

If the answer is a definitive no, cut it out. This is one of the easiest ways to rectify uneven narrative pacing.

If you’re not sure – perhaps there’s a vital moment in there but the scene isn’t quite working, you’ll probably find that one of the underlying issues is with the pace. You can attempt rejigging this by reading aloud and seeing if that helps identify a problem, such as uneven dialogue.

One of the main causes of poor pacing are scenes that either drag the story with their length or in their brevity disorientate the reader. Both instances can be a symptom of scenes that lack purpose. Being absolutely ruthless about what is needed and what isn’t to move the story forward will help root out these indistinct and unnecessary scenes.

Slowing Down Narrative Pace

Often a screenplay will suffer from overly fast pacing, which can disorientate the reader and make it hard to keep up with the story. So let’s take a look at a few ways to slow down the pace.

1. Subplots

Subplots will shift the focus to a subplot will help decrease the pace of the main storyline’s progression. They provide variety and help bolster the weight of the story overall.

Subplots can:

- Create conflict and tension.

- Trigger a shift in tone.

- Strengthen thematic ideas.

- Introduce new characters.

- Provide backstories and context.

- Reveal character motivations.

However, it’s important to strike a balance when including subplots, as too many narrative strands can clutter the story and make it complicated for the audience to follow. Always ensure they are essential to your plot and not just there for the sake of it.

Subplots should ultimately support and accentuate the primary arcs, giving the audience something different to get their head around whilst also keeping within the same theme and motivation of the screenplay overall.

2. Use Flashbacks and Backstory

Similarly, another way to divert focus from the main narrative is to implement flashbacks.

- Going back in time to show what happened in the past can break away from the story, simultaneously halting the current action and providing additional context to it.

- Mere glimpses into the past, meanwhile, can create suspense and anticipation. This kind of tension progresses the main storyline forwards as well.

- Moreover, flashbacks can be used to reveal further information about characters at a time when you think is most suitable for the audience to be privy to it.

Again, be careful not to use flashbacks for the sake of it. Make sure they fulfil a purpose in the story. Otherwise, they can become tiresome and feel like an overused trope intended to give the screenplay dynamism rather than adding something meaningful and important to the story.

Like any plot device, if you want to use flashbacks, do so judiciously. That way, there will be a greater emotional impact on the story and the pacing will even out, continuing to unfold the story impactfully.

3. Moments of Reflection

You can balance fast-paced action scenes with breathers like moments of reflection. These are used to control narrative pace, but can also benefit character development. This is an important part of crafting a believable story.

An intriguing and exciting plot is essential, but it won’t mean anything if we don’t understand or particularly care about the characters involved in it.

Moments of reflection flesh out characters by demonstrating their emotions, inner conflict and motivations, allowing the audience to connect more deeply with them.

An example of this can be found in Marvel’s Spider-Man: No Way Home.

Spider-Man Example

The ‘Condo Fight’ scene between Peter Parker/ Spider-Man and the Goblin is expertly built up with arguably the best depiction of Peter’s ‘Spider-Sense’ warning him of danger.

- The tension is increased, with a high-pitched ringing sound drowning out muffled and distorted voices from the other room.

- A tracking shot follows an alarmed Peter as he tries to figure out the threat.

- Willem Dafoe’s performance of the shift in demeanour from Norman to Goblin is chilling. The other characters are on edge and so are we. Stakes are rising.

- The fight breaks out and the pace ramps up. We’ve got explosions, chases, and chaos as the other villains make their escape.

- It results in the saddening death of Peter’s last remaining family member, Aunt May.

We pick up at the house of his best friend Ned, who is with Peter’s girlfriend MJ. A couple of minutes into this scene comes the highly anticipated reveal of Tobey Maguire and Andrew Garfield, reprising their roles as Spider-Man.

Following the exhilarating but devastating fight, and a comedic five minutes with the multiverse Spider-Man reveals, we are given a quieter moment with Tom Holland’s Peter Parker. He’s on top of the school building, wrestling with his grief and upcoming decisions.

This is quite a turning point for the character, film and franchise as a whole. We are given the space, like Peter, to re-orient ourselves and process our own reactions.

- The sequence of events is just under half an hour and takes the audience on quite a rollercoaster of emotions.

- It functions in multiple ways, structurally, thematically and catering towards audience expectations.

- Overall, part of its success is its pace; taking the audience through an intense journey, sparking a range of emotions and balancing moments of excitement and recovery, keeping eyes glued to the screen.

Speeding Up Narrative Pace

Tired of slowing things down? Let’s look at how we can get the story going a little faster. Sometimes this is what is called for; keeping the audience hooked by moving things at an exciting and propulsive pace.

1. Removing/Limiting Subplots

We’ve mentioned how subplots are great devices to slow the pace down. You might, however, encounter the opposite problem, in which you have too many subplots. This can become messy, detracting too far from the main narrative.

Multiple subplots aren’t an official requirement. So, if your story demands a far more linear narrative, limiting or removing subplots could be beneficial. It should make the narrative run more smoothly and keep the audience’s focus on the main storyline.

It can definitely be worth cutting out any unnecessary plot points that complicate the main narrative. Everything should ultimately be focused around your story’s primary driving purpose. If a subplot isn’t completely necessary in helping articulate this purpose, then it’s perhaps worth sacrificing for the greater good of a propulsive pace that keeps the story moving and doesn’t distract too much from the main arc.

2. Snappy Dialogue

One way to create fast-paced scenes is to shape your dialogue.

For instance, in Hot Fuzz, the dialogue is slim. Rapid and witty jokes combine with punchy lines of action, which, in turn, push the narrative along.

This reflects the pace of the movie as a whole and the signature style of Edgar Wright’s Cornetto Trilogy. One of the trademark staples is whip-pan shots and snappy editing. Mundane actions, such as a character getting ready in the morning, or transitional moments of police procedure, are edited frenetically. In short, Wright gets to the point.

Dialogue is a great way to advance plot and highlight tone. Hot Fuzz avoids coming to a slump, the pacing ensuring that the audience is entertained throughout. The dialogue also, meanwhile, helps convey the film’s action-pastiche tone.

But good dialogue is more about being witty and superficially fast-paced, it’s about maximising the scene’s efficiency. Great dialogue leaves a lot to the imagination, conveying the minimum of what is needed and allowing other elements, such as visuals and internal conflict, space to express the story within the scene too. Every line must have meaning.

So if you’re looking to maximize your dialogue, root out every line that doesn’t have a deeper meaning to the characterisation, narrative or theme moving forward. This can be a key way of speeding up the pace and making sure scenes don’t lag.

3. Increase the Action

There are many ways you can do this. But a race against time is one of the most common.

This could be a high-stakes action-thriller where your protagonist has limited time to save the people they love, and the world – perhaps like James Bond in No Time to Die, for example.

Or they could be rushing to the airport on time to prevent the love of their life from leaving, eg. Ross and Rachel in Friends.

On the whole, any sense of urgency will increase the pace. However, it’s worth remembering that it’s probably not a good idea to just blow something up for the sake of it. Creating a big, high-risk event that increases the action should only be done if it works structurally and for the overarching plot and character development.

For instance:

- What is it changing?

- What decisions is it forcing the character to make?

- Do these decisions fit in with their overall character arc? Does it, for example, force them to overcome a long-held fear?

- How is it leading into the next scene?

- How is it justified by the previous action?

4. In Medias Res

Sometimes scenes are padded with too many unnecessary beats. We don’t always need to see everything that leads into the action; i.e. your character walking up the driveway and ringing the bell.

Have you ever watched something and thought that it lingered far too long? Especially after the main point of the scene had already happened or before the meat of the scene is reached.

Solving this comes with being more ruthless in your editing. Take out what isn’t necessary and may be hindering the narrative pace and audience enjoyment. One popular pacing technique is ‘in medias res’. This is a Latin phrase, meaning “into the middle of things”.

It’s often used to kick-start the story off with a bang, usually delving straight into the disrupted equilibrium and the main character’s problem. It throws the audience into the crucial action and forces them to have to work and question what’s going on.

“Get in, get out. Don’t Linger. Go on.”

Raymond Carver

If the narrative suits it, and you’re looking to capture people’s attention right away, the urgency that comes with beginning ‘in medias res’ can be very effective.

It works particularly well if you’re intending to gradually reveal information throughout the narrative, since it promises to fill in the details later. It makes the most of the cinematic form, plunging the audience into the middle of the action and not wasting time on the boring bits of getting there.

5. Cliffhangers

Cliffhangers are a popular plot device, especially if you’re writing for television.

- They leave the audience wanting more, desperate to find out what happens next.

- They maintain a sense of uncertainty.

Most of us have probably had the experience of watching a TV show, telling ourselves it’ll be the last episode and then having it end on a cliffhanger. Those who can’t resist temptation or are incapable of delayed gratification in a binge-watching world will have scrambled for the remote to immediately start the next episode.

Of course, much of the compelling mystery needs to be built up through the storytelling and lore of the show itself. But the tension from a cliffhanger will drive the narrative pace forwards, dictating it at a speed that holds the audience’s interest.

The cliffhanger drives the story forward by leaving the audience desperate to know more. It lays down a starting gun, giving the audience a reason to keep watching and a sense of unfinished business. It’s typically a slow moment before a fast one, holding the audience’s attention by promising something to come.

In Conclusion

The biggest aspect to keep in mind surrounding narrative pacing is how essential it is to maintain a good balance. That means manipulating the rise and fall, fast and slow, sprinkling in the right amount of subplots and flashbacks, or being far more ruthless and direct.

You’ll need to both increase the pace and slow it down. There is a rhythm to great writing and so much of that rhythm is about where and how the increase and decrease of pace occurs.

Narrative pacing can be one of those frustrating aspects of screenwriting that feels instinctive. Knowing where to place points of pressure will come from inherently understanding the tension and release nature of storytelling in general.

But the above methods show how you can achieve such points of pressure and the fundamental dynamics that go into achieving them. This, in turn, will help you understand how you can have the desired effect on your audience.

A master of narrative pacing is someone who can have the audience in the palm of their hands. And the first step in achieving this mastery is knowing how you can achieve a particular desired effect. This is followed by understanding how each of these effects balance with one another. In this harmonious balance, truly great narrative pacing is attained.

– What did you think of this article? Share It, Like It, give it a rating, and let us know your thoughts in the comments box further down…

– Struggling with a script or book? Story analysis is what we do, all day, every day… check out our range of script coverage services for writers & filmmakers.

This article was written by Molly Hutchings and edited by IS Staff.

Get *ALL* our FREE Resources

Tackle the trickiest areas of screenwriting with our exclusive eBooks. Get all our FREE resources when you join 60,000 filmmakers on our mailing list!

Thanks. I have learned a lot. I did actually put most of my characters in the front, but I reintroduce them toward the middle and end. I will re-write and see if I can introduce them later in this screenplay.