On the Nose Dialogue: How to Lose It or Use It in Screenwriting

Granted, writing on the nose dialogue might not be the greatest sin in screenwriting terms. But it’s often the quickest way for a screenplay reader to view your work as unprofessional and, frankly, amateur.

Sometimes, what was originally effective back-in-the-day but is by now well-worn dialogue, is even referred to as being ‘on the nose’.

Ultimately on the nose dialogue can be a huge turn off to potential producers, managers and agents. It can often mean they’ll stop reading your screenplay on Page 1. Let’s dive in to what actually constitutes OTN dialogue…

What is ‘On the Nose Dialogue’?

On the nose dialogue is where a character speaks with no subtext. They say exactly what they are thinking or feeling in no uncertain terms.

Robin Russin and William Downs define it as follows in their book Screenplay: Writing the Picture:

‘When a character states exactly what he wants it’s called on-the-nose dialogue. The character is speaking the subtext; there is no hidden meaning behind the words, no secret want, because everything is spelled out. But most interesting people, and certainly most interesting characters, don’t do this.’

On the nose dialogue is so unconvincing because people don’t speak like this in real life. Human beings don’t usually say exactly what they’re thinking.

- So when screenwriters write characters that speak in this way, it sounds awkward and contrived.

- It takes the audience out of the story by reminding them that they are watching something fictional.

Eavesdrop on conversations on the metro or at the pub. You’ll see that people tend to imply meaning, deploying subtext, rather than frankly stating their feelings.

Here’s an example of a scene in an retirement home littered with on the nose dialogue:

In this example, Julia and Barbara sound like robots rather than real people.

- They don’t really seem to communicate with each other at all.

- Instead, each statement is merely a thinly-veiled mechanism for us, as an audience, to learn important information.

This is primarily because there is no subtext in either Julia or Barbara’s speech. Throughout, the two characters speak in flat, depthless statements.

The rest of this article will use this scene (from a sample script) as a template to demonstrate how to avoid using on the nose dialogue.

How to avoid using on the nose dialogue?

We’re going to take a look at four main tips for avoiding on the nose dialogue.

Tip# 1 – Show don’t tell

1. Make your characters talk less

One easy way to identify on the nose dialogue is by asking yourself…’could I get my character to perform an action that will show what is being said, rather than just having him/her saying it?’

- If the answer is yes, then show them doing this action, rather than having them explain it to another character.

- This is an easy and effective way of eliminating on the nose dialogue and making your characters more authentic.

In Barbara and Julia’s scene, we could eliminate much of Barbra’s dialogue and use other scenes to depict what is being said.

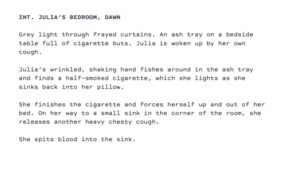

This screenplay would be much more effective, for example, if we had a preceding scene that worked like this:

This scene would allow us to get rid of both of Julia’s comment ‘I coughed some blood this morning’, and also—Barbara’s entirely expository remark—‘you’re a smoker’.

2. Actions and Reactions

In putting characters into situations, viewers get to see how these characters react. This is instead of merely re-telling the situation.

In real life, we learn a lot about people from the way they react to certain events and scenarios.

Events help us to read each other, and so in films they help develop and deepen characterisation.

Take the Julia example…

- For example, how does Julia respond to spitting blood?

- Is she terrified? Does she collapse? Is she strangely cold and unmoved?

- Each response tells us a lot more about Julia than having her merely re-tell the action.

A great example of this approach is in the opening scene (above) of Lynne Ramsey’s You Were Never Really Here.

We have one line of dialogue– ‘airport’– in ninety seconds and yet, because he comfortably fights off a crowbar-wielding assailant, we already know the following about the protagonist:

- He is experienced in combat.

- He has enemies.

What is more interesting than both these things is the protagonist‘s reaction to this action; he is nonchalant.

- We now know this is a character not only used to beating people up, but also accustomed to people trying to kill him.

Showing rather than telling adds to the drama, gives characters more depth, and avoids on the nose dialogue.

Tip#2 – Not the thing

Making characters talk about something else, and not revealing the thing that the context supposedly demands, can be a really effective way of creating poignant moments and avoiding on the nose dialogue.

A classic example would be in Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction where two hitman discuss cheeseburgers on a job.

The fact that they talk about something so frivolous at this time is actually far darker than having them talk about, say, different murder techniques.

- It’s an incredibly effective way of demonstrating the pair’s nihilism and distorted morality.

- This is done without them actually mentioning their profession.

In the Julia and Barbara screenplay imagine showing Julia cough up blood in her bedroom, and then having her sit with Barbara and not mention the blood at all.

It could go like this:

This scene is now pregnant with subtext.

Tip#3 – Exposition: a scalpel not a chainsaw

Exposition is the information an audience needs to know about the characters, the plot, or the world they inhabit. If they don’t know this, they won’t understand the story.

Unfortunately, a writer’s eagerness to convey necessary information means exposition often leads to on the nose dialogue.

In the Julia and Barbara example, all of the exposition is on the nose. The screenwriter wants to tell us that:

- Julia coughed up blood that morning.

- Julia is a smoker.

- Julia’s mother died of lung cancer.

- Julia is going to see the Doctor soon.

- Julia and Barbara are dependent on one another.

At times, expository dialogue is unavoidable, but here are some tips for using exposition that isn’t on the nose:

1. As discussed, show rather than tell

If it is possible to show a necessary piece of exposition through action rather than dialogue, then it is usually a good idea to do so.

- In the given example—four of the five points that the screenwriter wants to convey could easily be shown rather than told.

- The only exception is ‘that Julia’s mother died of lung cancer’. This is likely going to be a piece of information that needs to be relayed, rather than acted out.

- As demonstrated, information that Julia is a smoker, and that she coughs blood, are both easy to establish by using a preceding scene.

- Similarly, we could use a succeeding scene, to show Julia with the Doctor, rather than revealing this detail in dialogue.

Julia and Barbara’s dependance on one another is something that should be shown, in words and actions, over the whole length of the film, rather than in one direct, artificial line.

2. Try to allow exposition to emerge organically.

Expository dialogue is on the nose when it is awkward and contrived. It is possible, however, to reveal essential information in a much more organic way.

- Rather than simply re-telling details, allow them to emerge over the course of conversations between characters.

- Make two characters engage in conflict, for example, in order to reveal the required exposition.

Here is an example of scene between Julia and Barbara where a required pieced of exposition—the death of Julia’s mother—emerges more naturally.

Conflict and minimisation (the way Julia’s mother died is no longer explicit) makes this scene engaging, develops characterisation, and allows exposition to feel more natural.

3. Spread exposition out

Reveal details to the viewer piecemeal, rather than in one go, to avoid on the nose dialogue.

Artificiality is easier to spot if a high volume of expository information is given in a short space of time. Rather than trying to reveal five details, as in Julia and Barbara’s scene, reveal just one or two.

If you’re writing a feature, you have the space to drop these details in over time. Sprinkle little pieces of exposition across scenes.

4. Placement

Hand in hand with the spread of exposition is its placement.

Exposition tends to be boring, and is often awkward, so be wary of where you put it in your screenplay.

For example, you wouldn’t want to put an expository scene right at the start, because anyone watching your movie would be much more likely to switch off straight away.

Write a scene that draws an audience in, hold their attention, and then provide exposition. Alternate between more visual, action-driven scenes, and expository scenes– or even combine the two.

5. Minimise

Ask yourself if the information that you’re trying to convey is absolutely necessary. If it’s not, then get rid of it.

Then ask yourself if all of that remaining information is absolutely necessary.

For example, do we need to know Julia’s mother was a smoker that died of cancer? For the sake of argument, let’s say we do.

- Then we should ask– do we really need to know all of that?

- Or can we just let viewers know part of that detail; for example, that she died of cancer or that she was a smoker.

Don’t patronise your audience; allow viewers to work things out for themselves, rather than spoon-feeding them detail after detail.

6. The newcomer

One way to make exposition less forced, and be less vulnerable to end up writing on the nose dialogue, is to have a character who is new to the world/ characters/ set of rules.

- That way, we can learn with the character.

- And the given information feels far less artificial.

Movies and TV shows do this all the time.

In Andrea Arnold’s American Honey, for example, the protagonist joins a travelling sales crew as they tour around America.

- We learn the rules of selling magazines and the social cues of this specific group of runaway adolescents, with her.

In Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket, on the other hand, we have a whole group of newcomers.

- We learn with all these new recruits– about military boot camps, Vietnam, and the psychology of war.

Tip#4 – Narration and soliloquies

Narration

Screenwriters often offer on the nose dialogue when they are over-eager to let us into a character’s head.

One way to offer access to a character’s thoughts without using on the nose dialogue is using ‘voice over’ narration. This is where a character speaks their thoughts out loud over the action.

Narration can be powerful. But typically it is at its most effective when serving a purpose other than to just provide exposition.

For example, imaginative and meaningful narration features in Paolo Sorrentino’s The Great Beauty.

- We are granted access to Jep’s (the protagonist) feelings without him having to voice them to another character.

- The poignancy and reflective nature of the diction is what ensures this is narration that is engaging and moving, rather than cliched and uncomfortable.

- We learn crucial information about Jep’s character and past.

- But we also get more than that. We get thematic musings and philosophy, helping shape the tone of the movie.

Soliloquies

Soliloquies are when a character speaks their thoughts out loud.

- They are another way to offer access to what someone is thinking and can be useful in avoiding on the nose dialogue.

- Soliloquies are much more commonly used in plays, with narration favoured in film, but they are occasionally effective on screen.

A notable example would be in House of Cards, where Frank Underwood continually breaks the fourth wall and delivers soliloquies to the audience.

Again, these soliloquies need to be well-defined in their purpose.

- If it’s unclear why they are featuring, they might just seem like a stylistic flourish or trick, an empty shortcut to making the script feel more dynamic.

Finally, when on the nose dialogue works…

Occasionally, screenwriters will deliberately deploy on the nose dialogue. There are typically two main reasons why:

Comedy

As discussed, on the nose dialogue often sounds absurd and robotic to the point of being comedic.

Julia and Barbara’s conversation (in the first example) is so artificial that it is perhaps best interpreted as deadpan comedy.

Yorgos Lanthimos is an example of a filmmaker who exploits the frank awkwardness of on the nose dialogue to an uncanny and comedic effect.

- The Lobster is a prominent example of this.

- The dialogue is funny and bizarre because it’s on the nose.

Earned, poignant moments

There are times, usually towards the end of a film, when characters speak with a frank flatness. Somewhat contradictorily, these statements are powerful because of a lack of subtext.

- These are rare moments of total honesty where the simplicity of the blunt on the nose dialogue has a moving and powerful effect.

A great example is in one of the final scenes of Little Miss Sunshine…

Frank, played by Steve Carell and Dwayne, by Paul Dano, have a heartfelt chat. Frank says ‘I’m glad you’re talking again Dwayne’.

- It’s on the nose dialogue, but it’s emotional and effective because it’s appropriate for the context…

- Dwayne hasn’t talked for the whole film. Whilst Frank has often been emotionally guarded.

- To see the two characters being open and honest, and enjoying it, is actually refreshing.

In Conclusion

So on the nose dialogue can sometimes work. But it’s all about context.

Most of the time on the nose dialogue feels like an undramatic, un-cinematic and unimaginative way of getting across theme, plot or characterisation.

It will be a turn off to audiences, producers or any screenplay reader because it will seem lazy and unsuited to screen.

If you’re going to use on the nose dialogue, you better have a clear purpose. This purpose will need to be well expressed and closely tied to the tone of the script overall.

For example, if the world is surreal, the dialogue being surreal will make more sense. But if you’re trying to draw an audience into a convincing story and world, on the nose dialogue will likely only prove to be a barrier.

- What did you think of this article? Share It, Like It, give it a rating, and let us know your thoughts in the comments box further down…

- Struggling with a script or book? Story analysis is what we do, all day, every day… check out our range of script coverage services for writers & filmmakers.

This article was written by Charles Macpherson and edited by IS Staff.

Get *ALL* our FREE Resources

Tackle the trickiest areas of screenwriting with our exclusive eBooks. Get all our FREE resources when you join 60,000 filmmakers on our mailing list!

Just want to point out that in High School there was a huge fire in Malibu. Kids had members of their families that might be burning to death at the moment or trapped. I decided to start writing down what I heard people excitedly saying around me. I was shocked that everyone was speaking in what I now know would be called “on-the-nose dialogue.” “I’m scared.” “Their car isn’t going to make it through the wall of flames.” “No one’s home to save my grandmother.” “My dog must be terrified. He’s waiting for me to rescue him.” “My horse is going to die.”

Really useful article with clearly defined different alternatives to “on the nose” dialogue and why they should be used. The salient film clip examples really clarified each point made.

Thanks Angela so glad this was helpful to you!

Great to get advice on how to avoid on the nose dialogue instead of just being type not to use it. Thanks!

Most welcome Lynnette!

In this article, and in general, I really love the depth you discuss and the examples you give. I think you have a clear philosophy and can articulate it well which helps people like me learn.

Thank you!

Many thanks Alexander, glad our posts are helpful to you.

One of the best articles I’ve read on this. I had read once that people speak “on the nose” when they’re fighting, but it didn’t always ring true in my scripts (from the feedback I was getting). This article gives me a better understanding of why.

The article was great. It was informative. I loved it very much. Now I am informed. Now I can stop writing on the nose like this train wreck of a comment.

Glad it helped you Sean!