In film and TV, great monologues have the power to hit an audience more than any other moment in a story. They can be gut-wrenching emotional confessions, pivotal moments of characterisation or grand thematic statements.

Audiences remember monologues for these reasons. And great monologues are ones that condense and encapsulate a key part of a story.

In this article we’ll look at:

- What is a Monologue?

- How Long is a Monologue?

- How Do You Write a Monologue?

- What Makes a Great Monologue?

- 10 Great Monologues.

What is a Monologue?

A monologue is a long speech delivered by one character.

Sounds pretty simple. But there is a shorthand that comes with monologues that audiences have come to implicitly understand.

Monologues originally come from theatre, where a character will typically deliver a speech to either another character or as an aside to the audience. However, it’s important to note that usually a speech delivered to the audience will be considered a soliloquy rather than a monologue.

From this ancient form, the tradition of monologues has formed. And we, as hardened audiences, understand the shorthand of this format. When a character embarks on a long speech we don’t see it as odd or out of keeping with the drama. Instead, we understand this is a moment for us to listen to, an important reveal on the character’s part and a potentially crucial bit of information about the story’s theme.

How Long is a Monologue?

The both simple and complex answer is that there is no set length for a monologue. However, it’s generally understood that a speech said by one character for more than a minute constitutes a monologue.

That doesn’t sound like very long at first, but a minute of screen time can often feel like an eternity, especially when coming within the context of dialogue that is typically exchanged back and forth. Furthermore, on the page, a monologue will also seem longer. If most dialogue is a line or two long, a monologue may be a page or more.

Often rather than literal length, it’s the rhythm and tone of a speech coupled with that length that makes it a monologue. A monologue is a character talking for a long time. But it’s also a mood, a certain way of a character talking that is different from the surrounding dialogue. It can be, in a sense, a scene break.

Whilst there are no strict limits to the length of a monologue, there should obviously be restraints put on the length of a monologue. A great monologue will capture the audience’s attention and imagination with length and tone but cut short just at the right time.

Put simply, if a monologue goes on too long the audience will get bored. Attention will drift not only from the scene and film itself but from the focus of the monologue and of the story overall. A monologue can’t be an opportunity for the writer or audience to get distracted. It may be long but it needs to be as laser-focused and efficient as any other piece of dialogue or element of the script overall.

How Do You Write a Monologue?

A monologue needs to come at an appropriate point within a scene, otherwise, it will feel jarring. Again, there are no strict rules. But there’s a reason that great monologues often come at certain points within a script. This reason speaks to the purpose and effect of monologues.

Being that a monologue can sum up a certain theme, character aspect or sentiment, the end of a scene is a good place for it. It leaves the audience thinking over its meaning and it provides a definition and purpose for the scene.

However, you’ll also see monologues at the beginning of films or TV episodes. Here the monologue will act as a kind of mission statement, presenting the character in question straight to the audience and often laying out the themes of the upcoming story.

Furthermore, monologues often serve as a way of signalling a shift. This could be a narrative shift, transitioning the story from one place to the next. Or it could be a thematic shift, the monologue calcifying themes that have been bubbling. Or a monologue could signal a key development in a character arc, a change that the plot has exerted on this particular character.

Literally speaking, executing a monologue within a screenplay is as simple as it being a long passage of text on the page. However, pacing is crucial to the monologue coming off convincingly. An ill-timed monologue, coming out of nowhere, can really throw off the pacing and flow of a scene.

Consequently, any potential effect it might have will be undermined by the feeling that it is out of place. This can lead to it feeling transparently expositional, as if it’s obvious that the writer is trying to elicit a certain reaction from the audience or straining to convey information.

What Makes a Great Monologue?

If a monologue is too open and flowing it will seem overly expositional and lacking in sufficient subtext. A great monologue needs to strike a balance between giving away too much and leaving a tantalising feeling of wanting more.

It needs to reveal something that couldn’t be revealed in a more regular dialogue exchange. A great monologue is an opportunity to give insight into a character or theme in a unique way, a way that only a monologue could do.

A great monologue grips you for a short period of time and takes you on a journey, before dropping you off from that journey wanting more. It’s a time to briefly forget everything else in the story and focus narrowly on what’s being said in that very moment.

10 Great Monologues to Learn From

So let’s take a look at 10 great monologues that illustrate what monologues can offer a screenplay.

1. The Wolf of Wall Street – “I’m Not F*cking Leaving!”

This isn’t the only speech that Jordan Belfort (Leonardo DiCaprio) gives to his employees (and us) throughout The Wolf of Wall Street. The film is peppered with voiceover narration to the audience and gripping monologues. But this monologue to his employees certainly feels the most impactful of the film.

Jordan has gathered his company employees to announce his retirement from the company, having come under increasing scrutiny for the reckless and illegal practice undertaken by his brokerage firm, Stratton Oakmont.

But as he comes to terms with parting the company that he founded, he becomes emotional. He sums up his vision of what the company encapsulates about America, capitalism and opportunity.

- To illustrate his point, Jordan points out an employee, Kimmie.

- He tells the story of how successful she is now but also of how she came to him in very different circumstances.

- When she first joined the company, she was three months behind on her rent and couldn’t pay her bills. She asked Jordan for an advance of $5,000, which Jordan not only gave her but increased to $25,000.

“This right here is the land of opportunity. Stratton Oakmont is America.”

Jordan might be telling an inspiring story. But he’s also reaffirming his beliefs. He’s allowed himself to do all the heinous things he has done because he frames it in the context of ‘opportunity’. This despite the fact that in giving this opportunity, Jordan is defrauding others.

This a great monologue because it encapsulates Jordan’s ego and the ego of Wall Street in general. Jordan believes his company is what makes America great. Others see this plainly as fraud and greed run amok.

This great monologue also perfectly illustrates Jordan’s characterisation. In letting his ego get the best of him as he gives his speech, he ends up exactly the opposite of where he started the monologue, pledging not to leave the company with the immortal reveal – “I’m not fucking leaving!”. This will eventually be Jordan’s downfall as time will prove he should have quit whilst he was ahead.

2. Shawshank Redemption – “Rehabilitated?”

In Shawshank Redemption’s final act, Red (Morgan Freeman) has a great monologue that proves both heartbreaking and inspiring. When asked if after serving 45 years of imprisonment Red feels ‘rehabilitated’, Red delivers a calm, sombre takedown of the whole concept of prison rehabilitation.

He rubbishes the term ‘rehabilitated’, asserting that it’s just a ‘made-up word’ intended to serve those on the other side of the law than the inmates. It’s a profound insight, one revealing of a man jaded by a lifetime in prison and one that sums up of the film’s main themes.

Red goes on to illustrate how far away he is from the man that was imprisoned 45 years ago…

“I look back on the way I was then. A young stupid kid who committed that terrible crime. I want to talk to him. I want to try and talk some sense into him. Tell him the way things are. But I can’t. That kid is long gone and this old man is all that’s left.”

This strikes as a great monologue primarily in its sentiment, which is tragic. Red implies he’s lost his life to a stupid action he committed when he was a young man. Furthermore, he suggests the whole point of being in prison has little merit, rubbishing the concept of rehabilitation, on which the American prison system is built.

A sad monologue, however, is given somewhat of a sweet ending when we see Red’s parole application is given an ‘approved’ stamp. In not even trying to prove that he has been rehabilitated, the parole board feel that he has been.

3. The Dark Knight – “Now I’m Always Smiling”

In the middle of The Dark Knight, the Joker (Heath Ledger) interrupts a party, holding the guests hostage. As he singles out Rachel (Maggie Gyllenhaal), threatening her with a knife, he teases her with a tale about how he got his terrifying scars…

“So I had a wife, beautiful, like you. Who tells me I worry too much, who tells me I oughta smile more, who gambles and gets in deep. The sharks, one day they carve her face. We have no money for surgeries. She can’t take it. I just want to see her smile again. I just want her to know that I don’t care about the scars. So, I stick a razor in my mouth and do this to myself. And you know what, she can’t stand the sight of me. She leaves. Now I see the funny side. Now I’m always smiling.”

This is such a great monologue as it creates a terrifying visual picture of a traumatic experience. The Joker tells a sad, dark story, rich in tragic imagery and pain. The context also makes this a great monologue, the Joker holding Rachel in a vice-like grip, not letting her squirm away and demanding with his demeanour that she listen to his story.

Furthermore, as the film goes on we see the Joker tell many different stories of how he got his scars. Was this story of a girlfriend true? We’ll never know. This ambiguity makes the story all the more chilling, showing the depths of the Joker’s dark imagination and the mystery to his character in general.

4. The Devil Wears Prada – “Stuff”

In The Devil Wears Prada, Andy (Anne Hathaway) is just getting used to her new job as she watches her boss, Miranda Priestly (Meryl Streep) and colleagues put together a cover outfit. Andy scoffs when they debate over two types of belt that she thinks look the same as one another.

This scoff prompts Miranda to ask ‘Something funny?’. Andy, flustered, explains that she doesn’t know anything and is still learning about ‘this stuff’. Miranda seems perturbed by Andy’s use of this word, ‘stuff’. She explains to Andy the journey that an item of clothing or style will go on from high fashion to a high street store that Andy is likely to frequent.

“…That blue represents millions of dollars and countless jobs. And it’s sort of comical how you think you’ve made a choice that exempts you from the fashion industry when, in fact, you’re wearing a sweater that was selected for you by the people in this room…from a pile of ‘stuff'”

This is a great monologue in how acutely it sums up the fashion industry, particularly in defence from those who think it is ridiculous. Throughout the film so far, we’ve been on Andy’s side, seeing the fashion industry as frivolous and over the top.

But this great monologue brilliantly illustrates the complexity of the fashion world. It’s a brilliant explanation to those who think runway fashion is silly, demonstrating how fashion filters down to consumers.

The monologue marks a change in the film, a point of no return at which Andy will embrace her new job and the fashion world more and more. Of course, she’ll still ultimately see its flaws and stupid elements (as we will). But this monologue illustrates complexity where we might previously have just seen frivolity.

5. Good Will Hunting “Your Move Chief”

In Good Will Hunting, Will (Matt Damon) and Sean (Robin Williams) are yet to click. Sean is a therapist and has just taken on Will as a client. But he’s struggling to get through to him and Will is testing his patience.

Meeting on a park bench, Sean confronts Will about his arrogance. Sean couldn’t really care less if Will rejects his help at this point. But in confronting Will truthfully Sean hopes to pierce Will’s tough, guarded and arrogant exterior. Instead, he hopes to highlight Will’s naivety, inexperience and insecurity.

“If I asked you about art you’d probably give me the skinny on every art book ever written. Michelangelo. You know a lot about him. Life’s work, political aspirations, him and the pope, sexual orientation, the whole works right? But I bet you can’t tell me what it smells like in the Sistine chapel. You’ve never actually stood there and looked up at that beautiful ceiling…”

As Sean goes on, we can see that his words are having an effect on Will, who listens intently. Just the fact that Will has shut up for more than a few seconds proves Sean has broken through to him.

In simplistic terms, this a great monologue because it’s well written. A touching and powerful sentiment is well illustrated by Sean’s comparisons on the value of life experience outweighing knowledge gained from books.

“You’re an orphan, right? Do you think I’d know the first thing about how hard your life has been, how you feel, who you are, because I read Oliver Twist?”

But this great monologue also highlights a key change in the film’s arc. From this point on, Sean will start to break through to Will. Their progress will ultimately form the heart and soul of the movie and Will will eventually learn what Sean is outlining to him here – that studious knowledge is no match for lived experience.

6. Call Me By Your Name – “Right now…”

In Call Me By Your Name, towards the end of the film, a monologue touchingly illustrates a father and son bond. After Elio (Timothée Chamolet) has been left heartbroken by Oliver (Armie Hammer), Elio’s father, Samuel (Michael Stuhlbarg), seeks to comfort him.

But more than just provide comfort, Samuel provides his son with some context. He reminds him of his youth and encourages him not to get swept up in the intensity of how he feels right now and instead embrace all that made it possible.

“We rip out so much of ourselves to be cured of things faster than we should that we go bankrupt by the age of thirty and have less to offer each time we start with someone new. But to feel nothing so as not to feel anything—what a waste.”

The film has so far been short of these two characters bonding. And so this is a heartfelt and cathartic moment.

But more than that it helps hammer home the film’s themes. Elio and Oliver have an intense and passionate relationship that sadly comes to an end barely as it began. But that intensity and passion is the point of the story overall. The passion and intensity of youth, the way relationships soak into the self – the film defines itself this way.

As Samuel says himself, this monologue reminds us…

“Right now there’s sorrow, pain. Don’t kill it, and with it, the joy you felt.”

7. Pulp Fiction – Ezekiel 25:17

Cinephiles worldwide fan over this great monologue delivered by Samuel L. Jackson in Pulp Fiction.

When hitmen Jules (Samuel L. Jackson) and Vincent (John Travolta) seek to retrieve a briefcase for their boss, gangster Marsellus Wallace, they come across a business partner who has potentially double crossed Marsellus – Bret.

As Jules lords over a terrified Bret, he quotes from the bible, a passage – Ezekiel 25:17. When he finishes the passage, Jules ruthlessly shoots Bret dead.

“…And I will strike down upon thee with great vengeance and furious

Anger those who attempt to poison and destroy my brothers

And you will know

My name is the Lord when I lay my vengeance upon thee”

Part of why this great monologue is so popular is because of its timing. Jules uses the bible to damn Bret for his treachery and does so with a theatricality that is both terrifying in its judgment and cool in its swagger.

This passage also comes back later in the film, in the final scene.

- Jules talks of how he has made a habit of reciting this speech before he kills people. But here he questions what it means.

- Where previously it seemed Jules was the “righteous man” mentioned in the passage, he now questions what role he and those he executes take within the different roles of the “righteous man”, “the evil men” and the “weak”.

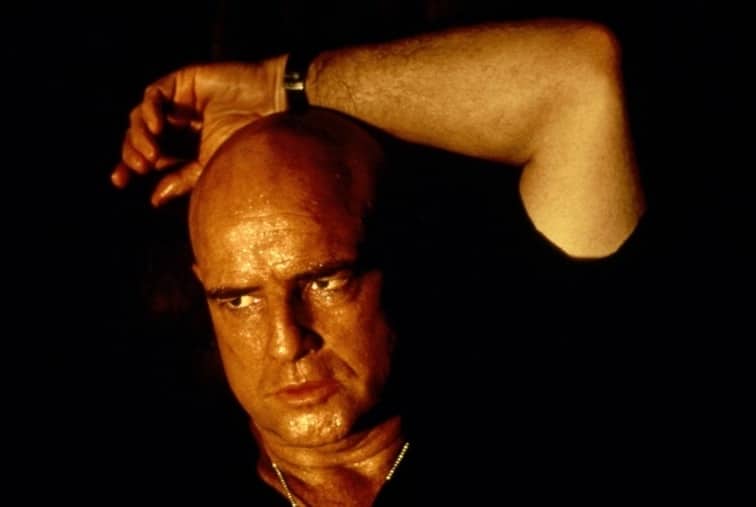

8. Apocalypse Now – “Horrors”

Colonel Kurtz’s (Marlon Brando) monologue towards the end of Apocalypse Now brilliantly surmises the film’s profound main theme. A colonel who has gone off the rails, hiding away in the jungle, circumspectly explains to the soldier (Martin Sheen) sent to assassinate him, why he’s gone down the path he has.

“I’ve seen horrors… horrors that you’ve seen. But you have no right to call me a murderer. You have a right to kill me. You have a right to do that… but you have no right to judge me. It’s impossible for words to describe what is necessary to those who do not know what horror means. Horror…horror has a face… and you must make a friend of horror…”

Kurtz’s thesis speaks to the hypocrisy of the war being fought in Vietnam and from those at the top of the American military. Real violence and true horror corrupts those who experience it. The officials who are shielded from this horror, those making the key decisions, can’t ever truly understand what it means.

This theme makes up the primary purpose for Apocalypse Now, a film intended to satirise the absurdity of war and be honest and raw about the true horrors it entails.

This is a great monologue in that it encapsulates these themes. But it’s also great because of its context. Kurtz has been a mystery throughout the film, a villain for Captain Willard (Martin Sheen) to find and kill. Here, protruding from the darkness, Kurtz reveals his humanity and provides clarifying insight into his situation and the reality and “horror” of war.

9. On the Waterfront – “I Coulda Been a Contender”

Sticking with the great Marlon Brando, this iconic monologue from On the Waterfront is often cited as one of the best of all time.

- Terry Malloy (Brando) blames his brother Charley (Rod Steiger) for dragging his life down.

- Terry was a promising boxer,until he got dragged into his brother’s dealings with a mob-connected union boss. Said union boss had instructed Charley to have Terry deliberately lose a fight so that he could win money by betting against him.

- When Terry considers testifying against the union boss for his involvement in a murder, Charley comes under pressure to silence his brother in order to save him from being murdered.

- Terry resists this and laments the path Charley has led his life down…

“You don’t understand. I coulda had class, I coulda been a contender, I coulda been somebody, instead of a bum, which is what I am, let’s face it. It was you, Charley.”

A tangible sense of regret defines this great monologue. It touches on a resonant and heartbreaking theme, the idea of promise and potential squandered by the recklessness of others. Terry is an empathetic, morally centered character and he’s dragged down by those around him, his own family even. This monologue cathartically highlights this point.

10. Gone Girl – “Cool Girl”

Amy Dunne’s (Rosamund Pike) great monologue in Gone Girl touches on an intriguing theme within what, at first, seems a relatively straightforward thriller. We learn that Amy has gone missing and see her husband, Nick Dunne (Ben Affleck) in distress. But as the film goes on we get more and more of an insight into Amy and into her and Nick’s marriage.

In a monologue, Amy highlights the role she played during their marriage. She recounts all the things she did to appease Nick, whether he knew it or not, conforming to an accepted standard and vision of a man’s ideal woman, what she titles, ‘cool girl’.

“Cool girl is hot, cool girl is game, cool girl is fun, cool girl never gets angry at her man, she only smiles in a chagrin, loving manner…”

This is a great monologue is how it ruthlessly deconstructs all the ways in which men expect women to conform to their ideal. We see this monologue play out to a montage of Amy contradicting all these standards and stripping her former self. She eats junk food, wears no makeup, un-dies her hair and reinstates reading glasses.

This monologue takes the film to another level. The story ceases being merely a thriller about a missing woman and a perfect marriage interrupted. Instead, it becomes one layered with mystery and deceit, as well as an interrogation of societal misogyny.

In Summary:

A monologue is a long speech delivered by one character. The form originates from theatre, where a character will deliver a long passage of speech either to another character, to themselves or to the audience.

There is no strict necessary length for a monologue. However, a monologue will rarely last less than a minute of screen time. Often rather than literal length, it’s the rhythm and tone of a speech coupled with its length that makes a monologue. A monologue is a character talking for a long time. But it’s also a mood, a certain way of a character talking that is different from the surrounding dialogue.

3. How Do You Write a Monologue?

A monologue needs to come at an appropriate point within a scene, otherwise, it will feel jarring. There’s a reason that great monologues often come at certain points within a script, commonly at the end, beginning or a turning point.

Literally speaking, executing a monologue within a screenplay is as simple as it being a long passage of text on the page. However, pacing is crucial to the monologue coming off convincingly. An ill-timed monologue, one coming seemingly out of nowhere, can really throw off the pacing and flow of a scene. Make sure your monologue comes at a place where it can signal a shift, either narratively, thematically or in terms of character arcs.

A great monologue needs to strike a balance between giving away too much and leaving a tantalising feeling of wanting more. It needs to reveal something that couldn’t be revealed in a more regular dialogue exchange. A great monologue is an opportunity to give insight into a character or theme in a unique way, a way that only a monologue could do.

A great monologue is not just about the language used. It’s about timing and pacing within the rest of the script. Utilise the uniqueness of this dramatic form to really hammer home a theme, character or plot development to the audience.

- What did you think of this article? Share It, Like It, and let us know your thoughts in the comments box further down…

- Struggling with a script or book? Story analysis is what we do, all day, every day… check out our range of script coverage services for writers & filmmakers.

Get *ALL* our FREE Resources

Tackle the trickiest areas of screenwriting with our exclusive eBooks. Get all our FREE resources when you join 60,000 filmmakers on our mailing list!

Thank you for composing thus article. Your examples and explanations of how they’re driving the story into another lane are enlightening.

Awesome article, thanks.