1. Your Story Idea Needs Animation?

a) Specific Scenes and Characters Will Be Better With Animation

b) Your Film Genre Will Be Easier or Better in Animation

Many animated films often employ the fantasy genre or science fiction genre, because it is easier to create those worlds using animation. Also, many children’s books or comics fall into one of these genres, and are adapted into animated films (did you know that the HARRY POTTER movies were originally pitched as an animated film series by Steven Spielberg?)

But this doesn’t mean animated films need to be in the fantasy or science-fiction genre, or even have anthropomorphic characters.

Animation can overlap with almost any film genre or sub genre. And that can work to your advantage. Again, think about what animation brings to your story that couldn’t be brought by live action. Does this bear relevance to the story and its purpose?

c) No, Your Live-Action Film Should Not Be Made Into An Animated Film For Convenience

Given how diverse animation is becoming, with different styles and genres being used (and especially with the rise of adult animation in TV), you could argue that any script could become animation.

But that’s not true. Many films should be live-action, because that will be the best medium for it.

Yes… if you want to make a live-action film into an animated one, you can always do that (look at the animated episode of THE BLACKLIST that came out this year due to Covid shutting down their production). But if your project will be better as live-action, you may want to wait for it to be filmed with real actors.

Now some may point to the 2019 Award-winning French animated film I LOST MY BODY, and say that could have easily been live-action. It is in a contemporary modern setting and features adult human characters.

But there was a specific reason that their team chose animation: the severed hand. The story is of a severed hand making its way back to the young man it was detached from.

That odd character would have been ghastly to look at, even in a CG-realistic form. Yes, it doesn’t have any dialogue, but it is obviously crucial to the story. And so they needed to make it an animated film. The animation served a distinct purpose in palatably realising a quirky and crucial (and otherwise gruesome) aspect of the story.

2. You Need To Be Detailed In Your Descriptions

Unlike in live-action, where a description is relatively self-explanatory, animation actually requires more details in your descriptions.

Scene Descriptions

Given that you are already creating entire worlds, you can not only set the film in exotic locations like the jungle, desert, tundra, or another planet, but you can also easily have a brief cutaway shot or flashback to another exotic location.

You can (largely) forget budget constraints and how to difficult and costly it would be to get cast and crew to the other side of the world for a scene lasting 45 seconds. With animation you can cut to anywhere you want for however long you want. This freedom can lead to a freedom of creativity.

FAMILY GUY is a great example of how the freedom of animation lets the show cutaway all the time for very brief periods of time for comedic purposes. It is now the show’s signature and represents its distinctive style of comedy. Some would even argue that the show embraced this style too wholeheartedly and that its comedic power came to overwhelm the show.

Prop Descriptions

Furthermore, when you write in a car or a house into your scenes, you won’t just get a car or a house that exists somewhere on the backlot or in a storage facility. You will have artists literally creating any kind of car and house you can envision. So put those details into your original screenplay.

So much time and effort will be put into each visual element that carefully considering the look and feel of each element in the screenplay is the best way to embrace the form.

Character Descriptions

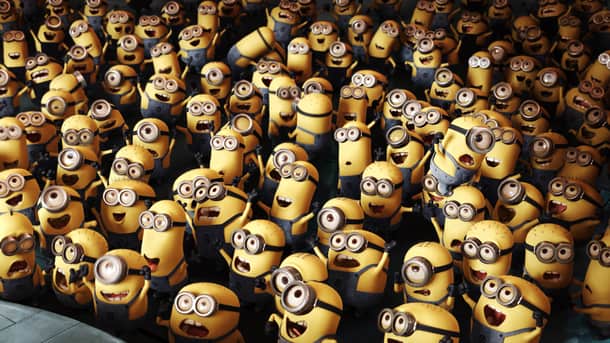

Furthermore, animated characters are exactly that: ‘animated’. They can have odd body shapes, come in different colors, and their facial features can be exaggerated. For example, think of the Minions from DESPICABLE ME and their spin-off MINIONS. They are unique, unparalleled creations and their popularity proves the appetite for such creations.

Also, one of the principles of traditional animation is ‘squash and stretch’, meaning that characters and objects can do exactly that in animation. They don’t have to move realistically, so remember that as you write them. While you will not be the one ultimately in charge of character design, don’t be afraid to steer them in a particular direction.

Now obviously you don’t want to be too detailed for two reasons:

- You need to leave some artistic license to the talented artists, who will want to put their own stamp on the film.

- You need to recognize that although animation is technically a limitless medium, there are budgetary and time constraints that you will need to consider.

Someone will need to make every asset (ie prop, object, person) that you mention in your script. And in most cases, that ‘someone’ will actually be an entire team. So be economic in what you include and what you don’t.

But in creating main characters or settings, that will be used multiple times throughout the film, recognize that these artists also enjoy a challenge. Give them something to really show off their skills. Create a unique and challenging world, thus challenging creators to realise it.

3. Your Animated Script Will Be Storyboarded

Animation, especially in feature film form, is an iterative process. The script will go through many different phases and individuals prior to completion. In short, it is very collaborative. One of these early phases will be storyboarding.

A group of animators known as the ‘story team’ will be responsible for creating storyboards that visually translate the script (many live-action action and superhero films now utilize this process in ‘previsualization’).

These storyboard panels will be edited together to make a crude hand-drawn animated scene called an ‘animatic‘, so that the team can get a sense of timing.

Why Is Storyboarding Important?

The purpose of storyboarding is figuring out:

- what works and what doesn’t visually

- how to make the story stronger

- planning shots/angles

- where to add physical humor

- focusing intensively on character expressions or movements

- timing the shots / creating an animatic

- refining the director’s vision as much as possible before animation begins

So be aware: your script may drastically change during this process. But if you have difficulty taking feedback, or have a specific vision that you are not willing to sacrifice, it may be difficult to work for animation.

Also realize that it will take 2-3 years to make an animated film (maybe longer). During that time, due to feedback from the story team and production needs, you might have to do multiple (if not dozens and dozens) of rewrites. It may seem tedious, but try and look at it as a great chance to perfect the script.

4. Animation is Usually Aimed at Family Audiences

Since Walt Disney created the first animated feature film SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN DWARFS over 80 years ago, the vast majority of animated films have been aimed at children.

Although… earlier this year, Kristine Belson, the president of Sony Pictures Animation, made a comment that more animated features in the future will be made for adult audiences, and deal with PG-13 or R-rated topics.

Indeed, a film such as SAUSAGE PARTY or a TV series such as BOJACK HORSEMAN prove that animation can be squarely aimed at adult audiences. In these examples, animation is crucial to the humour and imagination of the story.

But… given the history of animation, and its strengths, the majority of animated films will continue to be for children and family-friendly audiences. To follow the ‘family-friendly’ formula, you will most likely have the following:

a) The Lead Character is a Child or is Like A Child

If your film is family-friendly, this will mean that your main character will either be a kid, or have a child-like quality or perspective. Kids need to relate to the character, so this is important.

Your lead character should have qualities like:

- trusting of everyone

- need for acceptance

- curiosity / wonder

- innocence / naivety

- insecurity in themselves

- a wanting to be an ‘adult’ / have a purpose

Your protagonist needs to essentially be a character that a child watching could empathise with. Someone they see themselves in, someone they recognise or someone with characteristics they recognise. For instance, Shrek isn’t a child. But his identity as a lonely outcast helps the audience empathise with him.

b) Family-Friendly Comedy

Animation is also well-known for including comedy. In the last few decades, featuring a well-known comedian as a supporting character accomplished this successfully.

Examples of this include Robin Williams as the genie in ALADDIN, or Eddie Murphy as Mushu in the original 1998 animated film MULAN and as Donkey in the SHREK series. Not only does this help solidify the comedy, it’s often a knowing wink to the parents of the children watching. A well-known comedian will help sell the film to adults and a well characterised comedic role will help sell the screenplay to said comedian.

Screenwriters often say that comedy writing is more difficult than writing for drama. In comedy, you not only have to balance a compelling plot, but you must also infuse it with comedic dialogue and situations. And in many ways, writing ‘family-friendly’ comedy is no doubt more difficult than general comedy.

You can‘t have

- curse words

- sexual references

- extreme violence or murder

You can have

- slapstick/physical humor

- potty humor (to a degree)

- pop culture references

- clever and witty ‘family-friendly’ dialogue

If anything, the process of writing for family audiences will make you a stronger comedy writer, because it takes away some of the tools that many comedians and comedy writers rely on. It will force you to learn how to create clever comedic dialogue that is appropriate for all ages.

Both children and adults love music. For this reason many animated films will include songs. So you may end up collaborating with a composer (or if you’re talented enough, write them yourself). And moments like the sounds of the environment: dripping rain or a bustling city can be taken from a royalty-free music platform.

c) Strong Relationships and Moral Themes

But if you think of many of your favorite animated films, they aren’t simply comedy. They have strong and genuine relationships (as kids like to see reinforcement of community and of family). They will also nearly always have moral themes at their heart (as kids are still learning about what is right and what is wrong).

For a screenwriter this is important. The purpose and message of your film needs to be at the very genesis of your story idea. At their very best, animated films for children can help teach those children at a pivotal age.

You’ll notice recurring themes in many animated films – family, love, friendship, loyalty, community, kindness. Your message doesn’t have to fall into a tried and tested category. But in an overcrowded market, your script does need to have a purposeful and meaningful core message.

d) Music and Singing

Both children and adults love music. For this reason many animated films will include songs. So you may end up collaborating with a composer (or if you’re talented enough, write them yourself).

Music can be key in helping break up action and dialogue. Those who have children will know they don’t often have the longest attention span! Music and songs are just one way of giving variety to the action of your animated film. A different tempo, a different context, a different style – these all help in capturing and keeping eyes on the screen.

5. Animation Will Be Distributed to International Audiences

Dubbing

International distribution will require dubbing the film into multiple languages (sometimes even changing the animation of the characters mouths). Think of Disney’s FROZEN and how many different language versions of ‘Let It Go’ there were. There were over 40 different versions, sang by 40 different singers, in 40 different languages.

No, you’re not required to translate your script into dozens of other languages. But you should have ideas of how certain scenes could be easily modified to fit international audiences. Some cultural references just won’t translate, so be aware.

Take for example Disney’s ZOOTOPIA. For their newscaster scenes, they actually animated differently for different countries/languages. They used different animals with different voice actors (most actual newscasters from those countries). Ideas like this would be a great idea for the screenwriter to put forward at the development stage.

But most importantly, being malleable is key. You won’t be expected to outline how a scene could be different for 40 different markets. But leaving space in the script for flexibility will help widen its potential appeal.

Marketing + Franchises

Many major animated films are aimed at global audiences, and with the goal of becoming a global franchise (ie having multiple films and potentially spin-off TV series). If you are working with a studio, this will include international marketing and publicity campaigns, short-form digital content, and creation of consumer products (ie toys, bedding, clothing, etc).

No, yet again you will not be responsible for all that. But these are additional factors to consider as you write. Will studios want to spend money marketing your characters?

In screenwriting terms, what characteristics do your characters have that make them distinctive? What is it about your story world that will bring audiences back to it?

It’s important to not get ahead of yourself, thinking of sequels before you have even finished the screenplay for the first instalment, for example. However, thinking of the appeal and distinction of your core elements at their creation point, might give them wider potential later down the line.

6. Animation Screenwriters Have Less Rights to the Property Than a Live-Action Screenwriter

If you are in the UK, the WGGB (Writers Guild of Great Britain) luckily covers both live-action and animation equally (see details here).

However, if you are in the USA, you know that the WGA (Writers Guild of America) is the dominant writers union.

But in the world of animation, while the guild does cover some many adult animated TV shows including THE SIMPSONS, BOJACK HORSEMAN and BIG MOUTH, it doesn’t cover most animated projects, especially animated features.

WGA vs The Animation Guild

Rather, most members of the animation industry (including writers) are represented by The Animation Guild (I.A.T.S.E. Local 839). This includes many animation writers as well as all animation artists (but do know that you can be a member of both WGA and The Animation Guild!).

Compared to the Animation Guild, the WGA writers who write for animation will receive:

- residuals

- potential participation in merchandising revenue and Broadway ticket sales

The Animation Guild writers can try to negotiate these… but it is not guaranteed. For example, the writers of the original 1994 animated film THE LION KING received absolutely nothing for the recent live-action remake.

Why is it split?

This goes back to the history of animation. As said before, storyboarding was how stories were constructed for animation for years. Given that this was done by animators, it made sense for animation ‘writers’ to be covered by the Animation Guild. Although this changed in the late 90s and early 2000s, the screenwriters are still split.

How do I get the most out of my contract for animation?

If you a primarily live-action writer, you can certainly try to get jobs in animation. Due to the increased interest in animation (particularly in light of the Covid-19 pandemic), the WGA made a statement to its writers. They stressed that when negotiating to write an animated project, WGA members should:

- make sure that both the member and their agent/manager should take a stance that their work will be covered by WGA

- ensure that a WGA contract is used, as it will ensure they receive residuals, script fees, credit protections, and contributions to the WGA pension & health funds.

In Summary:

Make sure animation is the best form your story could take. There needs to be a distinct purpose behind the choice of writing an animated film. Embrace the freedom of imagination that an animated film can offer, utilising it to shape the tone, style, narrative and characters of your screenplay.

Be detailed in your descriptions. Remember that you are creating a unique and specific world and that your screenplay is the first step in a process encompassing teams of animators and designers. Let your imagination run wild but be efficient and clear in how you convey that imagination.

An animated film is a long, exhaustive process and storyboarding is key to this process as it breaks down the screenplay into visual steps. As a screenwriter, this won’t necessarily be your responsibility. But it’s an important step to remember when writing a screenplay for an animated film, as how you write will affect the storyboarding process.

Keep focused on the core message and purpose of your story and trust in any audience. Don’t patronise a younger audience but don’t cloy after an adult one.

Moreover, think of the bigger picture. An animated film has the potential to reach out easily across the world. Try, where possible, to prime you script for such an eventuality.

Because a screenwriter is just one cog of many in putting together an animated film, it can often feel like they are sidelined in the process. If embarking on writing an animated film, don’t be naive as to the overall process of making an animated film and the hierarchies that exist. Writing an animated film might seem like the easy option, removing the complications of live action filmmaking. But the complexities of bringing a screenplay to life remain whether you’re working with humans or cartoons.

- What did you think of this article? Share It, Like It, and let us know your thoughts in the comments box further down…

- Struggling with a script or book? Story analysis is what we do, all day, every day… check out our range of script coverage services for writers & filmmakers.

This article was written by Katherine Sanderson and edited by IS Staff.

Get *ALL* our FREE Resources

Tackle the trickiest areas of screenwriting with our exclusive eBooks. Get all our FREE resources when you join 60,000 filmmakers on our mailing list!

Great article, there is also THE QUEST, which I have fortunately found.

Thank you for the generosity and informative articles from your talented writers.

My outline will become my abbreviated children’s book, if that has sales, I have potential for “proof of concept” and an offering that will show tone, style etc.

It’s an idea and a start.

Will

For a beginner such me, this was purely informative. Many thanks Katherine Sanderson.

Glad we could help!

Family films are about families.

On the whole, I thought this article was helpful. Especially the emphasis on whether or not your story idea suits animation. If the reason for getting into animation is that your idea is intrinsically suited to animation then you may have a greater chance of success. One thing I would like to see is more information on writing animated short features. These were very common in the beginning of animation and think that the shortness of the features suits the medium. Many of the classics like Looney Tunes and Mickey Mouse were relatively short. Granted, these may have been simply storyboarded by artists, but screenwriters have great ideas for cartoons too, so we should be allowed to contribute. Thank you for the acknowledgement.

Thanks Jonathan, glad you enjoyed the piece!