We, however, have broken down the key elements to writing romantic comedy that will satisfy your audience. In a genre with many expectations, where do you start?

Table of Contents

Genres

Romance + Comedy

As the name suggests, a romantic comedy blends elements of both the romance and comedy genres and finds the perfect balance between them.

Ultimately, a romantic comedy is centred around a romantic relationship. There must be a romantic arc (or multiple) at the core of the story.

Don’t be afraid of being too straightforward when it comes to the romance, it is largely what the audience wants to see. Similarly, the audience didn’t sign up to see a tragedy or drama, so don’t let your romantic conflict become too dark or serious without being undercut with humor.

In terms of comedy, no comedy is universal. So if you try to write humor that appeals to everyone then it will likely miss the mark. Instead, simply write what you think is funny.

The comedic tone should be consistent. Whether it be slapstick, sarcastic, quirky, or dark try to stick to one. If the comedy is too overpowering or stretched too thin the film won’t feel right to the audience.

A comedy script should contain at least a few very memorable hilarious scenes and set pieces. So look for aspects of your romance story that are humorous and maximise them. Where are there misunderstandings and miscommunications? Who are the characters that will provide consistent humor?

A Third Genre

A lot of romantic comedies also expand into a third genre or a secondary setting. This can give the romantic comedy a new twist and make it more original.

Some of the most successful romantic comedies have been mixed with another genre. This could be sci-fi (About Time), teen (Clueless), or even superhero (Deadpool – a self-proclaimed “love story”).

This adds an interesting and fresh aspect to the film that engages audiences and also expands them.

Furthermore, don’t worry too much about relatability when it comes to genre and setting. The humorous trials of love are universal and the audience will always be able to relate to a well-written character and relationship arc.

So if when writing romantic comedy you find yourself slightly leaning into another genre, try and embrace the elements that will make the story feel unique within the romance genre. Exaggerating this new setting or element could add a distinctive spin on a well-tread narrative. Moreover, it gives the story a relatable beating pulse, something for the audience to grab onto in otherwise potentially new territory.

Romantic Comedy Protagonists

The audience goes into a romantic comedy knowing that the characters will end up happy. So the characters have to be complex and interesting. We have to like and root for them and above all enjoy watching them.

Most romantic comedies have two romantic leads. However, there are also ensemble casts with more than one romantic relationship, or just one protagonist with multiple love interests.

No matter what characters you choose to have, the audience has to fall in love with the characters before the characters fall in love with each other.

Consider these questions about your characters:

- Who are they?

- Why are they appealing to the audience?

- What are their admirable qualities?

- Do they have any flaws?

- What is their attitude towards love?

- What are their goals?

The last one is particularly important as it is what is driving your character, and acts as a sub-plot where their internal conflict also plays out. Everything about the character draws us in, even their flaws. It’s essential that the protagonist must be someone the audience recognizes and understands, even if they’re not always on board with their actions. The character must be worthy of rooting for when it comes to them finding love, not someone who seems like they don’t need or deserve it.

Matching One Another

Furthermore, are the two romantic interests’ goals compatible with each other? If not, then this could be a cause of conflict. There needs to be another aspect of compatibility that pushes them to resolve the problem.

Make sure your two leads are fully formed in their own right. When introduced separately at the beginning of the film the audience should be able to glean some idea of how they might meet or what the relationship will be like.

Is one a romantic and one a cynic? Or are they both career-driven and don’t prioritise relationships?

An easy trap to fall into is to have one character much more developed than the other. One may feel like a three-dimensional, believable character but the other may be a hollow plot device. This will ultimately undermine the persuasiveness of the romance.

The leads must also be relatable to the audience. More recently, this is seen in showing the protagonist‘s struggle and weariness within the culture of modern dating before they meet their love interest. However, having your lead dream of a fairy-tale romance can be equally as relatable.

Audiences are happy to suspend reality slightly. We may question how the protagonist can afford an amazing New York apartment as an editorial assistant for a fashion magazine. But ultimately it’s all arguably part of the fantasy. The two leads are a cipher for the audience’s wishes, whether that be via their relatability or their aspirational qualities.

Chemistry

One of the biggest differences between a good romantic comedy and a bad one is the chemistry between the love interests. In many ways, writing romantic comedy is dependent on the special connection you create between the two main characters. It defines the story and whether or not it is successful in terms of its romance and comedy. Great chemistry, after all, will provide both.

If their love isn’t believable then the whole foundation of the story collapses. It also links back to whether the audience roots for the protagonists. If it doesn’t seem like they should be together then why should we care if they are?

Of course, chemistry can also partly depend on casting, and some filmmakers are known to consistently cast actors with strong on-screen chemistry. Think Meg Ryan and Tom Hanks in You’ve Got Mail and Sleepless in Seattle, or Ryan Gosling and Emma Stone in Crazy, Stupid Love and La La Land.

Nevertheless, it is plot and character development that ultimately creates this chemistry. Shoving two stereotypically good-looking people together does not necessarily equal a match made in heaven. It has to be in the writing.

Writing Chemistry

When writing romantic comedy, chemistry can appear in different ways.

- Perhaps it begins as purely physical while the characters are at odds with each other like in The Hating Game. However, make sure antagonistic attraction isn’t too toxic or purely physical. The relationship shouldn’t be set up to fall apart after the credits roll because it’s been based on nothing but physical lust.

- Alternatively, the connection between your characters could be intellectual and emotional like in You’ve Got Mail. Here, the protagonists get to know each other on an anonymous email chatroom before discovering who they really are.

Make sure this chemistry is present throughout the film and that it builds. This could be through emotionally charged eye contact, fleeting touches, or witty banter. Don’t let them end up together just because the plot says so. Instead, make their connection the purpose of each scene they share, whether it’s building, thriving or fraying.

How does one character complement the other? Are their jokes falling flat until they meet this other person, who appreciates the humor? Do they have a cynicism that isolates them from everyone but the fated romantic interest?

Creating chemistry is all about creating connections. Why do these characters match each other well? How do they fit together like pieces in a puzzle? The answers to these questions will first lie in the characters’ unique characteristics and personalities.

So it’s important to build these elements before you start writing. It will be difficult to match your characters if they both have no depth or personality. Instead, it’s via the contours of their personalities that the two characters will slot together convincingly and satisfyingly.

Sidekicks

Another staple of romantic comedy is the sidekick or secondary character. They could be a best friend, a sibling or a colleague, for example. Their main role is to act as your protagonist‘s sounding board and confidant.

They can ground the character and give their honest opinion, which is often a clearer view of the situation and the one the audience sees. This is normally pointing out that the lead’s current partner is actually (not so surprisingly) a horrible person or knowing the truth about the big miscommunication between the love interests.

For two romantic leads, they will often have one sidekick each. They are the foil to the main characters and also often the comic relief. The best sidekicks are the ones who are funny and endearing enough for the audience to enjoy their scenes and not want to skip back to the romance.

- For example, Spike (Rhys Ifans) in Notting Hill may say (and wear) some outlandish things. But it means we enjoy him in his own right and not just because he convinces Will to go get Anna.

- Notting Hill also demonstrates how the sidekick role can be represented by a group of friends too.

Of course in some romantic comedies, the sidekick ends up being the love interest in a ‘shock’ twist, accidentally and subconsciously falling in love during a scheme but failing to see what’s in front of them. In Just Go With It, for instance, Adam Sandler’s character realizes he loves his assistant (Jennifer Aniston) after asking her to pose as his fake ex-wife.

The sidekick ultimately though is a key vessel for the comedy side of writing romantic comedy, helping balance the love with some humor and often breaking the protagonist‘s lovesick view of the world.

The Romantic Comedy Formula

Most romantic comedies follow the same basic plot structure, with essential key moments. This formula is just the bare bones of the film and doesn’t mean it has to be predictable. Traditional tropes can be subverted or spun into something original to make your romantic comedy stand out. However, these bare-bones provide a brilliant starting point for writing romantic comedy.

1. The ‘Meet-Cute’

One of the most traditional elements of the romantic comedy genre is the meet-cute. This is simply, a first meeting between the two leads which is cute due to the fact that we know it’s the start of the love story.

As cliche as it may seem, the meet-cute is essential to the plot. It establishes the dynamic between the two love interests. The classic example is two characters bumping into each other and suddenly realizing an attraction.

This first meeting will often also be awkward, embarrassing, or hostile. This helps set up any conflict between the characters, perhaps a (sometimes mutual) dislike or embarrassment because of what’s occurred.

Or perhaps it’s love at first sight. But that may not stop a current partner from appearing to remind one of the leads they have somewhere to be and simultaneously shut down any sparks that may have been flying.

Either way, there must be mutual attraction or aversion, or both. You know a meet-cute when you see one. It should be our first sighting of the all-important chemistry.

The 18-hour car journey in When Harry Met Sally is a great example of a distinctive meet-cute moment. Not only is it a unique situation, but the scene brilliantly sets up the animosity that will carry through the film and their chemistry in the way they play off each other.

Of course, not all romantic comedies have a traditional meet-cute as sometimes the leads already know each other. This is typically best friends who don’t realize they’re perfect together or enemies that can’t see past their hatred. They could still have, however, a meet-cute in a flashback or just as the first time the audience meets them together, which can still set up the emotions and chemistry underpinning their relationship.

2. The Conflict

Once the main characters have met and established a friendship, relationship or an uneasy alliance, it is then time to put that relationship to the test.

This could be an ex-partner, a current partner, miscommunication, lies, doubts, or love triangles. It can be hard to find the balance between something that could destroy your couple’s relationship but is also something that can be resolved and moved past (in the film’s final act).

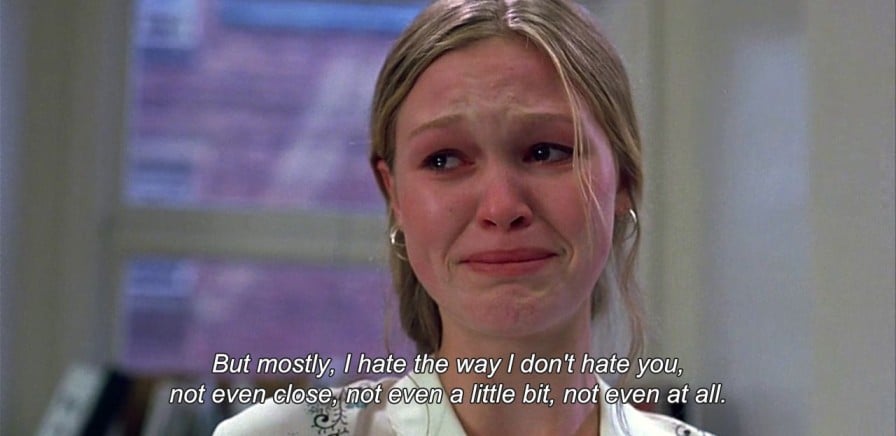

The conflict often prompts some introspection in the characters in whatever else is going on in their lives. And they use the time apart from their love interest to focus on their other goals or issues. In 10 Things I Hate About You, for example, Kat consistently clashes with her sister and father but only reconciles with them after her fight and break-up with Patrick.

If the conflict can’t drive the story forward then the audience hasn’t been on a journey with the couple, and as a result, will have less sympathy for them.

Convincing Conflict

One thing to note is to avoid having a character who sacrifices their goals in order to resolve the conflict. As romantic as it may seem to have someone give up a promotion for love, prioritising romance over every other aspect of life can feel like the protagonist sacrificing their happiness for the sake of the romance.

Furthermore, if you go down the route of a previous partner or a romantic false lead be careful not to make them too one-dimensional. They can’t be too nice because the protagonist needs a reason not to be with them. But they also shouldn’t be too cartoonishly horrible. In short, they have to feel like a believable conflict for the protagonist to be wrestling with.

Additionally, if using miscommunication as a device try not to make it something that could be cleared up in a minute-long conversation between the leads. This is frustrating to the audience and won’t create any empathy for the characters. Ultimately, it’s all about generating believable obstacles for your characters. How are they going to fight through their conflict and come out the other side?

3. The Big Gesture

The big romantic gesture is often preceded by a lightbulb moment where one or both love interests suddenly realize that they need to be with the other person no matter what. This will itself follow on from the conflict. It is the climax of the film, the moment everything has been leading up to and often the most memorable scene of the film.

The characters wrestle with the big conflict in the relationship, then something will prompt them to realize how or why they can get over the conflict. Usually, this realization will come at an inopportune moment, thusly providing another obstacle for the characters and relationship.

Most commonly, it is a big public declaration or a race to reach the other person. Rushing through the airport, a kiss in the rain, jumping in a cab and telling the driver to step on it, Harry running through New York on New Year’s Eve to profess his love for Sally.

This scene can have a comedic aspect to it but is more often where the romance takes the front seat. These scenes may be slightly unrealistic (and not always recommended to try in real life) but it’s an important cinematic moment that typically proves highly cathartic for the audience. It’s a set piece that will often be key to how the film is remembered; an exciting cinematic synthesis of tension, romance, music, humor and emotion.

4. The Happy Ending

Another key element of writing romantic comedy is crafting a happy ending. The fact the audience knows it’s coming shouldn’t make it any less satisfying or enjoyable.

There are many different types of happy endings, most traditionally it’s admitting feelings, getting married, or even a first kiss. However, ultimately it should just be the happy ending that makes the most sense for your characters.

Maybe happiness means something different to your characters, and they part ways amicably but with a new sense of hope or peace. In My Best Friend’s Wedding, for instance, Julia Roberts’ character accepts that her best friend loves his fiancé but is content with her situation at the end of the film.

Whatever the happy ending for your characters is, make sure it’s true to the story and to their character development. Any other internal or external conflicts should be resolved, and the audience shouldn’t be left wondering how they suddenly jumped to being happy.

Most importantly, your characters should stay true to themselves. They may have changed or grown positively but the goals and values they’ve had from the start should still be visible, and should be an aspect of their happy ending. A truly happy ending is about matching your character’s endpoint with their start point. Did they get what they want, whatever the route? Did they achieve their goal?

The romantic arc may not always turn out exactly how the protagonist or audience envisioned it. But in the end, the protagonist must satisfy what the missing piece was in their life at the story’s beginning.

Bringing it All Together

The romantic comedy film relies on two genres that complement each other perfectly. Love can be wonderful, awkward, unexpected, and fantastical and lead to lighthearted and hilarious situations. However, even when it’s hard and heartbreaking, humor can always be found.

It’s not just this balance that has created such a successful genre. These films are ideally driven by idiosyncratic protagonists and believable conflict. The stories challenge characters who we come to have affection for through three-dimensional and charismatic characterisation.

True satisfaction from a romantic comedy comes from the journey the protagonists have been on. How did they change? Have they achieved everything they wanted to? Audiences love being by the characters’ sides as they go from their lowest point to their highest point.

We know the happy ending is coming, but seeing them reach it through love, laughs, struggles, and simple human connection is pure joy. Writing romantic comedy is ultimately about giving your characters what they desire. In turn, you give the audience what they want. In seeing characters we grow affection for satisfied we cathartically connect with those on the screen and come away with that warm fuzzy feeling that a great romantic comedy can conjure.

– What did you think of this article? Share It, Like It, give it a rating, and let us know your thoughts in the comments box further down…

– Struggling with a script or book? Story analysis is what we do, all day, every day… check out our range of script coverage services for writers & filmmakers.

This article was written by Tallulah Allen and edited by IS Staff.

Get *ALL* our FREE Resources

Tackle the trickiest areas of screenwriting with our exclusive eBooks. Get all our FREE resources when you join 60,000 filmmakers on our mailing list!

Great clear and concise explanation. After reading, I want to create a romantic story. In terms of demand, such stories are popular, and in terms of rental rating they are inferior to biopics and trailers. Thanks anyway for the article.