Writing great dialogue is difficult, but one way to get a step closer is through the use of subtext. Subtext, literally what is below the text, is the deeper implication behind the surface meaning.

Dialogue is not the same as real speech. Dialogue is inevitably heightened, even if it’s simply a matter of removing spaces and stammers between words, or of making sure lines don’t overlap.

However, they do have something in common. In real life, as in fiction, people rarely say what they actually think or feel.

Irony and subtext

CASABLANCA, despite being written while it was being filmed, is one of the few perfect screenplays. While there are many choice iconic lines, this exchange, between Captain Renault and Rick early in the film, is a perfect example of subtext:

– And what in heaven’s name brought you to Casablanca?

– My health. I came to Casablanca for the waters.

– The waters? What waters, we’re in the desert.

– I was misinformed.

By this point in the film, the audience already know that Rick is an intelligent and strategic person. He runs a nightclub with its very own (technically illegal) gambling operation. From his previous scenes and the tone of his voice here, it’s clear Rick can’t have ended up in Casablanca by accident.

The screenplay reveals his backstory later. For now though, this great dialogue exchange tells us something more important about his character. Rick is sardonic, using sarcasm as a defence mechanism.

Sarcasm is created through the interplay of text and subtext. It uses irony, when someone says one thing and actually means the opposite. It engages the audience by making them, along with the other characters, have to actively read between the lines.

Here, the subtext of Rick’s explanation creates an intriguing character mystery. He doesn’t want anyone to know the real reason he’s here in Casablanca. Rick is open in his other dealings, even his corrupt partnership with Captain Renault. What could be so sensitive that he’d hide it from him, the closest thing to a friend Rick has?

A man, his wife and his hat

There’s a simple exercise that can prove useful for adding or finding subtext in dialogue:

- identify the most important word in a sentence of dialogue

- try rewriting the sentence without using that word

- does the scene change? Does its meaning change? How?

Characters can have entire conversations without ever exactly saying what they’re talking about.

Many arguments – in real life and in fiction – have this pattern. The dialogue follows a small, even petty disagreement. Underneath, however, the real issues between the characters are building, neither able to express them to the other.

Screenwriters can also load actions with subtext. Sometimes, writing great dialogue means knowing when dialogue is actually unnecessary.

William Goldman gives a few examples of successful uses of subtext in his indispensable book, Adventures in the Screen Trade.

One, which comes from author and screenwriter Raymond Chandler, features no dialogue at all:

A man and his wife are riding silently upward in an elevator. They are silent, the woman carries her purse, the man has his hat on. The elevator stops at an intermediate floor. A pretty girl gets on. The man takes his hat off.

This is not a scene about manners. It’s about a marriage in trouble. The subtext tells us, with wonderful economy, a helluva lot about that married couple. If, for example, the couple’s destination is a divorce lawyer, I wouldn’t be a bit surprised. Wherever they’re heading, they’re not giddily enchanted with each other. And if, a few pages on, they have a fight, the simple act of his removing his hat for the pretty girl would make a logical and movingly human trigger.

Great dialogue where the truth comes out…

Looking through lists of great dialogue in films or television, many of them seem to contradict this lesson about the power of subtext.

For example, this is the number one line on AFI’s list of the 100 greatest movie quotes of all time:

Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn.

However, these iconic lines wouldn’t be nearly as powerful or as memorable without their context.

Great dialogue allows a story or a scene to build up to these moments where the truth finally comes out, using subtext to play on what the audience the characters know.

In GONE WITH THE WIND, without Rhett’s ongoing mistreatment of Scarlett leading up to it, covered by a veneer of respectability and money, this last line wouldn’t be as shocking.

Genre and form can dictate subtext

Of course, the use of subtext is dependent on the story and genre. Not every character can be an enigma, nor should they be.

Melodramas and broad comedies will typically have less subtext than a more naturalistic drama.

On television, soap operas, sitcoms and episodic shows need to keep the audience up to date with the characters and their situation, regardless of whether they’ve seen the last episode. Sometimes, as a result, subtext and subtlety is less of a priority.

Serialised shows perhaps have more leeway. They can assume that the audience understand the characters enough to follow the differences between their words and what they actually mean.

I am the danger…

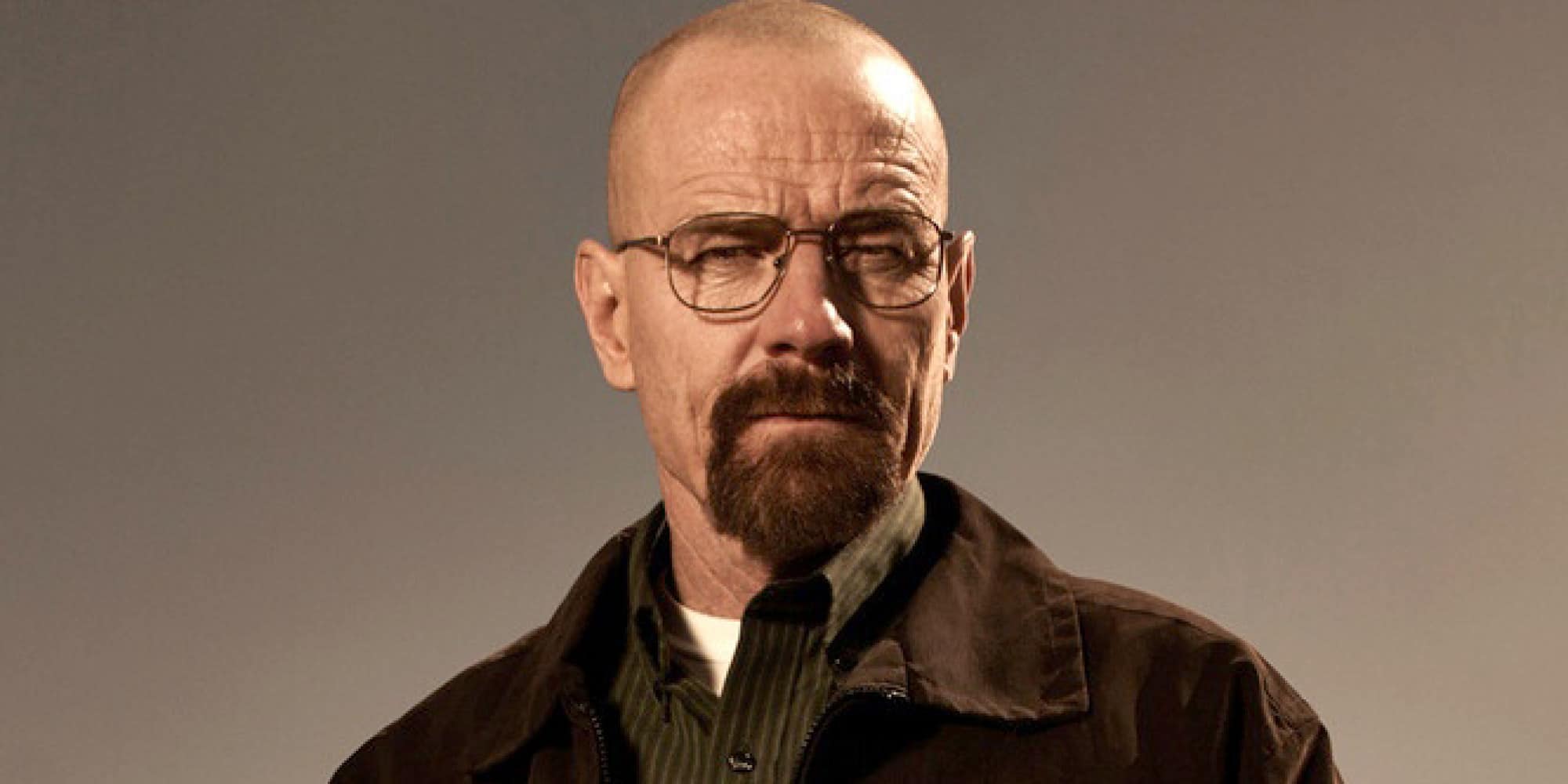

In BREAKING BAD, when Walter White tells his wife Skyler “I am the one who knocks!” it’s one of the greatest moments in a great show. Although she already knew about his involvement in the drug trade, he makes it clear that he’s more likely to be a killer than a victim.

This line arrives six episodes into season four. If the character hadn’t spent all this time pretending to be the same family man he always was, lying to his wife and son, this truth-telling line would be nowhere near as powerful.

There are still so many subtexts running through this scene, despite its ostensible bluntness. Walter is, on a deeper level, trying to prove himself to his wife, who he feels is questioning his masculinity and his ability to protect his family.

He does this by scaring her, assuring her that he is capable of considerable violence, that he is amoral to some degree.

This is the same kind of speech he might give to a rival drug supplier, and it’s the first time he really shows this side of his character to his wife.

Another subtext to his monologue, one the character isn’t entirely aware of, is that it shows he’s losing the ability to keep these halves separate, practically and psychologically. Taking it on face value – that Walter White is a hero who’s only trying to help his family – does a disservice to the layered writing.

I am the one who knocks!

If find that your dialogue falls flat, ask yourself if you’re making full use of the power of subtext.

What the characters aren’t saying can be as important, or more, than what they are.

If you enjoyed this article, why not check out our article OPINION: Lessons For Screenwriters From Films About Writers?

- What did you think of this article? Share it, Like it, give it a rating, and let us know your though in the comments box further down…

- Struggling with a script or book? Story analysis is what we do, all day, every day… Check out or range of services for writers & filmmakers here.

Get *ALL* our FREE Resources

Tackle the trickiest areas of screenwriting with our exclusive eBooks. Get all our FREE resources when you join 60,000 filmmakers on our mailing list!

Very informative. I appreciated the links within the article offering more insight.

Highly descriptive article, I loved that bit. Will there be a part 2?