History is, to gently mutilate a great quote, often stranger than fiction, which is what makes it such a great basis for fiction. Of course, mining history for a solid TV script isn’t as simple as shoving a good story into a period setting.

So what makes for a good period piece?

As always, there are a number of approaches to take and considerations to make…

Choosing a Unique Perspective

This is particularly true when the historical ground of your TV script is well-trodden (WWII, 19th Century England, or the Old West for example).

It boils down to identifying the ‘narrative hook’.

Setting as ‘Hook’

Take these two premises:

- Set against the backdrop of the Qinghai-Tibet war in Northwest China, a Tibetan supply-line worker begins an affair with a Qinghai local, but mounting pressure from the Qinghai army threatens the destruction of the supply line and the end of their relationship.

- Among the Victorian social elite, a young woman falls for her family butler, but the pressures on her to match above her station threaten their future.

This is obviously a somewhat exaggerated example, but both of these premises pay specific attention to historical setting as their ‘hook’ over and above character and plot, i.e. the setting itself is the basis of the conflict.

Of course, the former could be terrible and the latter great, but the point to note is that the extent to which the historical backdrop itself can sell the idea is diminished in the latter because we’ve seen it before.

Only the former can really use its setting as its ‘hook’.

Or, to put it simply: purely taken in isolation, the sentence ‘It’s a drama set during WWII’ isn’t as dramatically juicy as the sentence ‘It’s a drama set during the fall of Constantinople’.

But that of course doesn’t mean one period of history is somehow more ripe for drama than the other, simply that it’s important to bear in mind the level of ‘exposure’ that period of history may have had, which brings us to…

Perspective

So, if we’re operating in a narratively popular or simply well-known period of history, it’s important to make sure we have some other narrative hook.

This is why:

- MAD MEN shows us 1960’s America through the lens of the advertising industry

- VINYL tackles the 1970’s via the music industry

- THE DEUCE tackles the same period via the porn industry

- BOARDWALK EMPIRE examines prohibition-era America from the perspective of a corrupt town treasurer

These perspectives make their respective series because they completely reframe the period of history in which they’re set.

Something like, say, the civil rights movement in MAD MEN, a struggle more commonly framed from the viewpoint of the campaigners as their struggle against an oppressive system, is presented from the perspective of these detached, successful, conservative men who are less than on board.

That combination of characters we like and attitudes we don’t allows for a really nuanced dramatic dynamic.

A unique perspective can turn something we’ve seen ten times into something completely new.

Choosing a Perspective in Conflict with the History

The challenge with any TV Script, even over and above a feature screenplay, is establishing conflicts that can sustain the narrative for a long time.

The benefit of rooting a narrative in history is that it enables writers to draw on pre-existing conflicts to inform the story.

To really mine this conflict, however, it’s important to make sure that our core characters have some stake in that history in the first place.

Take MAD MEN. Matthew Weiner describes protagonist Don Draper as:

“…somebody who has been very lucky, who has struggled, struggled, struggled and got what they wanted – which doesn’t happen to everybody – and then said ‘Is this it?'”

It’s the mindset that plagues Don throughout the series, and it’s intimately tied to the period setting.

Placing a character like Don Draper at the back-end of the white-picket-fence, wholesome nuclear family, American Dream era of US history is perfect: he’s achieved that ‘dream’ just as the country enters a politically active era in which that way of thinking is continually challenged.

It’s the perfect climate in which to intensify his ‘Is this it?’ mindset.

Same with:

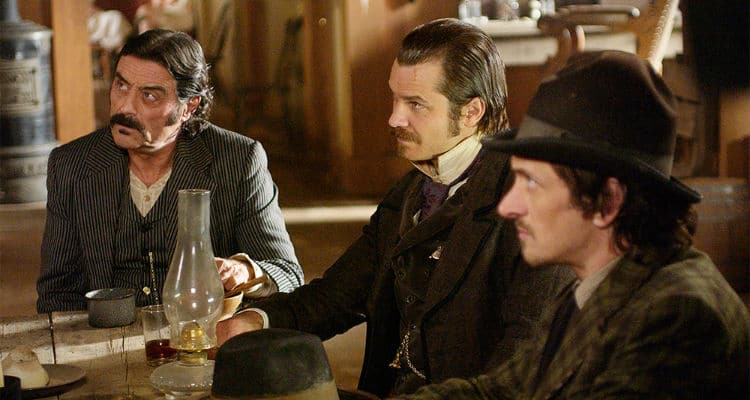

- Al Swearengen in DEADWOOD, a man with influence in a confined community, hopelessly opposed to the development of the union and American capitalism as he tries to fight the annexation of his town by the Dakota Territory.

- Enoch Thompson in BOARDWALK EMPIRE, who circumvents prohibition laws for profit and as such attracts the attention of law enforcement.

- Matthew Crawley in DOWNTON ABBEY, who struggles with and resists adapting to the aristocratic lifestyle of his distant family.

Setting the protagonists’ perspectives at odds with their historical setting or situation like this is the perfect way to create ongoing conflict and sustain a series.

Being Specific with the Timeframe

This is perhaps more pronounced in the more confined framework of a film, but it’s definitely worth bearing in mind in a TV script too.

History vs Narrative

One of the risks in adapting or even creating a story for a TV script set within a particular period of history is trying to cover a lot of ground in too little time.

It’s a trick of hindsight – it’s easy to view a particular period of history as being confined because we associate it with very specific ideas or images that end up protracting it in our minds.

So, if we’re told that a narrative is set during the Roman Empire we get these sudden flashes of praetorians, gladii, gladiatorial combat and so on and the fact that we’re talking about a period spanning some 1,500 years falls a little by the wayside.

A more protracted example would be a biographical piece.

It may be easy to note the key story beats in, say, Stalin’s transition from Marx-obsessed youth to meteorologist to political activist to dictator, but it’s just as easy to forget the real amount of time each of those ‘beats’ actually represents.

It’s the relationship between a story and reality. It’s easy to remember the latter as the former and forget just how drawn out it really is.

This obviously has some pretty significant implications for any narrative that seeks to mine this kind of time period.

If we want to cover all a character’s teenage years in the military, the coup they fronted in their 30’s, their rocky middle-aged marriage and their struggle with gout in their 70’s, there’s a risk of creating a kind of ‘montage effect’.

The need to jump ahead to get everything in can end up hampering the depth and nuance of that character, because the character is, pretty much by necessity, forced to change offscreen.

A Narrow View

MAD MEN’s ten-year narrative time-span took 7 seasons and 92 episodes to unfold.

FEUD: BETTE AND JOAN covers a production and its aftermath.

Each series of PEAKY BLINDERS so far has been confined within a year or two, ditto THIS IS ENGLAND.

This isn’t to say there isn’t scope to cover a broader period of history, just that covering a decade in a couple of episodes is likely to give your audience whiplash.

The narrower perspective allows the narrative to explore the direct consequences of a character choice within a clear framework. It lets us really explore an event or choice that really defines that character.

When Don Draper or Tommy Shelby makes a mistake, we can be sure we’ll see every aspect of the ramifications play out.

A more fragmented take on a broader period can force the audience to try and piece together consequences, after jumping ahead to a character who’s now undergone key developments we haven’t seen.

Simply put: it’s easier to weave a compelling story in a tighter framework.

Marrying setting with story/theme

This easiest way to illustrate this idea, and most others, really, is to turn to Shakespeare. Adaptations, specifically.

It may seem obvious, but the creative process doesn’t need to begin with location, backdrop, societal atmosphere and so on.

Sometimes we just have a story.

Let’s say that story concerns a boy and a girl from different warring factions who fall in love. We have core themes surrounding loyalty, love, and the conflict between the two.

- We could set it in 16th Century Verona, with two opposing noble families vying for political control. We know that works.

- We could set it in modern California, during a conflict between two mafia empires with competing criminal enterprises.

- We could set it in 1950’s New York, against a conflict between two working class street gangs from different ethnic backgrounds.

All of these maintain those core themes, but they provide an opportunity to explore them in different ways, be it via societal expectation and family values, crime, or racial divides.

So, what setting most lends itself to your story about a young, working class character who loses everything to a corrupt societal elite and vows to take action to change the structure of the unjust system around them?

- Set it in 19th century England and you have a story about class divides or suffrage.

- Shift it to 60’s America and you have a story about racial inequality.

- Shove it into Hong Kong in 1942 and you’ve got a story about the dynamic between natives and invaders.

It’s important to choose a setting that facilitates telling the story in the way you want to tell it.

Anthologies

For another approach to this idea we can turn to anthology series, where a single theme or idea plays out across multiple settings, allowing for varied explorations of that idea.

FEUD, for example, has a simple idea at its core. As Ryan Murphy puts it:

“I loved the idea of every season doing a two-hander that had a really emotional core to it.”

Taking that simple concept, the first series centres on Bette Davis and Joan Crawford and the second will telegraph the relationship between Princess Diana and Prince Charles.

It’s marrying core themes and ideas with different, but equally fitting, settings.

AMERICAN CRIME STORY works on the same idea, exploring the relationship between the public and private perspectives on high-profile criminal cases, a theme set to run through the O.J trial, the murder of Versace, the aftermath of Katrina and the Clinton/Lewinsky scandal.

If your story isn’t already intimately tied to a particular period or place, it can be worth looking at its core conflicts and themes and asking the question: where and when would facilitate these conflicts in the most interesting way?

Using History as a Backdrop

There’s a reason so many otherwise fictional narratives are set during or around the Second World War.

Aside from giving us, well, a past, history has also given rise to a kind of dramatic language.

Think how many action or adventure or superhero narratives use Nazis as their antagonists.

Why?

Well, Nazis and their related imagery have become so synonymous with evil that utilising them in a narrative negates the need to devote time to establishing an antagonistic ideology or motivation.

Drawing on that aspect of history immediately cements an idea in the audience’s mind. It’s a kind of shorthand.

Obviously, this risks coming across a little lazy but, if done well, using history as a way to inform the audience’s understanding of some key element of the story can work really well.

Skirting briefly away from TV, take PAN’S LABYRINTH: the brutality of post-Civil War Spain provides the perfect backdrop for Ofelia’s story, as she tries to deal with the horrors around her by retreating into fantasy.

The narrative doesn’t need to explore the history itself with too much depth because its central purpose is to inform the broader story, not to be the broader story.

Same with something like STRANGER THINGS, in which the purpose of the 80’s setting is geared toward nostalgia.

It allows the series to draw aesthetically on the kind of stories that inspired it and as such really concisely sets the tone for the audience.

As such, mining history for a TV script isn’t all or nothing. As with any other narrative tool, it is, above all else, about serving the story.

Get *ALL* our FREE Resources

Tackle the trickiest areas of screenwriting with our exclusive eBooks. Get all our FREE resources when you join 60,000 filmmakers on our mailing list!