Over the last few years, there has been a rise in the number of workplace dystopias in film and TV. But what are the essential elements of these stories? And why do writers return to the format again and again? We take a look at the key parts of workplace dystopias in film and TV, their context, inspiration and resonance.

Table of Contents

- The Rate Race on Film – What is a Workplace Dystopia?

- A Brief History of the Workplace

- Severance – a 21st Century Workplace Dystopia

- 1. Mundane and Surreal: The Office Space

- 2. “Low Overheads” – Neglect of Workers in Workplace Dystopias

- 3. Workplace Dystopias – Sharing is Caring?

- 4. The Little (and Large) Madnesses of Office Workers

- 5. Bureaucracy and Injustice

- 6. The Illusion of Freedom

- 7. Dark Designs: What are the Workers Working For?

- 8. The Everyman Hero

- In Conclusion

The Rate Race on Film – What is a Workplace Dystopia?

Workplace dystopias in film and TV come in as many varieties as there are types of workplaces. Equally, many films set in workplace scenarios can feel dystopian whilst being entirely real.

Dystopia: an imagined world or society in which people lead wretched, dehumanized, fearful lives.

Merriam-Webster

In this article, we’ll focus on films and TV depicting that most modern and ubiquitous of workplaces; the office. This seemingly mundane setting has been host to all sorts of mediations on the idea of the workplace as dystopia.

The most notable recent contribution to this genre is the critically acclaimed series Severance, which we will use as a touchstone to look at other workplace dystopias, and see what makes them tick.

A Brief History of the Workplace

Throughout the 20th Century, there was a dramatic shift in what a “workplace” looked like. The division of labor into individual repetitive tasks began in factories. Hailed by Henry Ford, this system maximized efficiency but minimized individual skilled human input.

Eventually this along with advancing computer technology spread into the world of white-collar work. Daily tasks in these roles can be so abstracted that work becomes mindless. We live in a time where much of the working world is busy punching numbers and letters into a computer from 9 to 5. Disconnected from the fruits of their labor, workers struggle to motivate themselves, or even truly understand what they are working for.

As a result “the office” has become a powerful aesthetic language and setting to ask big questions about the state of the world, and the value and purpose of human life. Even in the modern world of remote working and more flexible schedules, the office and the workplace, in general, loom large in the collective imagination.

And it forms the basis of many a story focusing on the struggles of the individual in a collectivist, often oppressive workplace.

Severance – a 21st Century Workplace Dystopia

Severance is a workplace dystopia with a simple but powerful premise; what if people could surgically separate their work memories and their home memories? Would people be able to live carefree pre and post-work existences, living in the present as if they never worked at all?

Severance answers these questions with a resounding no. Instead Lumen – the company offering this impossible dream – turns it into a living nightmare.

- The corporation brutally exploits the severed workers, using their memory loss to rob them of agency.

- Their permanent amnesia conceals the dark truth behind their work, and the abuse they suffer 8 hours a day.

- Perhaps worst of all, none of the voluntarily “severed” workers seem to be enjoying the peaceful home life they imagined.

In the world of Severance, the drive for a separate work and home life becomes an elaborate form of self-harm. It’s a high-concept take on the idea of workplace dystopia. And it’s one that makes for both a compelling and intelligent musing on office life.

So taking a step backward, let’s break down some of the creative choices that form this world, and how they echo other workplace dystopias.

1. Mundane and Surreal: The Office Space

What comes to mind when you think “office”? It might be strip lighting, scratchy carpets, aggressive air conditioning, water coolers, and of course, rows of plastic cubicles. The Lumen headquarters captures this essence and takes it to extremes.

The offices are an impossibly sprawling labyrinth of rooms and corridors, occasionally containing very unusual features, like a man nursing a herd of baby goats. The sheer scale of the compound makes it feel like a self-contained universe. For the characters’ “innies” who only remember their working hours, it may as well be.

The depiction of the office space is a key component of representing a workplace dystopia. Sometimes the familiarity and mundanity of a setting can make it feel surreal. The longer we stare at the same thing, the stranger it becomes. The more you say a word, the more you start to lose a sense of its meaning.

What are you going to reveal about the workplace by peeling back the familiar layers of its shell? You may lean into the more mundane aspects of a traditional office. Or you may even critique the supposed “perks” of the modern workplace. Overall, interrogating the workspace itself is an important ingredient in making your workplace dystopia resonate.

2. “Low Overheads” – Neglect of Workers in Workplace Dystopias

A common way the misery of office work is portrayed in workplace dystopias is to emphasize the physical discomfort of the spaces with surreal twists. As in Severance, the 1999 classic Being John Malkovich also juxtaposes the surreal and mundane in its depiction of offices.

- Craig Schwartz is a talented but unsuccessful puppeteer, pressured into taking a temp job by his frustrated wife.

- On arriving at his new clerk job at the Mertin-Flemmer Building, the protagonist finds the office between the 7th and 8th floors.

- The ceilings are so low, they force staff to crouch as they walk around. The boss explains his choice of office by citing the “low overheads”.

- The strangeness continues when Craig discovers a tunnel behind a filing cabinet, leading inside the mind of John Malkovich.

Aside from demonstrating a serious commitment to puns, the absurdly low ceilings of the office literally oppress the workers. Bending them into uncomfortable shapes, they remind us that basic human needs are less important than profit margins.

In this way, the workplace becomes a dystopia, using an imaginative twist to both metaphorically and literally demonstrate the pressures and dehumanizing effects of the workplace on its workers.

3. Workplace Dystopias – Sharing is Caring?

Terry Gilliam’s 1985 film Brazil uses the office aesthetic to similar effect. Inspired by Nineteen Eighty-Four, the world of Brazil is polluted, hyper-consumerist and almost devoid of human connection.

- Sam Lowry starts his new job in “Information Retrieval” in an enormous industrial building. His office is a dingy cubicle on a corridor with hundreds of identical metal doors.

- He is settling in when his desk begins disappearing through the wall. On investigating, he finds he is actually sharing the desk with a worker in the room next door.

- A fight ensues between them; this is apparently not a world where people share.

As in Being John Malkovich, it’s an entertaining visual gag that serves a dual purpose. By choosing to place a wall over the desk, the corporation cuts their equipment costs, whilst also maximizing efficiency by preventing social interaction between workers.

In Severance, meanwhile, the office features the sinisterly named “break room” where workers are punished for misbehaving. To reach the room they must walk through a dark corridor, so narrow their shoulders brush the walls. Once again, we see restrictive spaces reflecting the suffocating nature of conforming to office environments.

How workers interact with each other is vital to the portrayal of a workplace dystopia, as the pressure inflicted by the workplace forces the people within it to either band together or come apart.

4. The Little (and Large) Madnesses of Office Workers

If you’ve ever worked a boring office job, you know there are some characters who crop up in every place of work. Whether it’s an obsessive food-labeler, a stationary hoarder, or a mini-dictator, people seem to develop certain quirks to get them through the day.

The perpetually strip-lit lives of the “innies” in Severance kicks this tendency into overdrive. One, for example, develops a religious commitment to the values of the corporation’s founder. Another greedily collects performance rewards in the form of branded finger traps and post-its.

In Richard Ayoade’s 2013 film The Double (based on the novella by Fyodor Dostoevsky), Jesse Eisenberg plays Simon James.

- A shy and unremarkable office drone, he has been in his job for 7 years.

- None of his colleagues seem to notice him, and one day a new hire called James Simon arrives.

- To Simon’s horror, James looks exactly like him, except he is charismatic, suave and outgoing.

- Before long, James has become popular at work and manages to steal the attention of the women Simon has been pining for.

In this story, the office and his colleagues become a metaphor for the protagonist‘s inability to have a starring role in his own life. No matter how loud he shouts, he is unable to make himself heard as a valuable and individual human amidst this oppressive and dystopian setting.

This shows how in a workplace dystopia, the setting will typically exert itself on the protagonist and/or supporting characters. In this way, workplace dystopias often become psychological dramas. The external pressures of the work environment significantly alter and affect the characters’ minds, eventually forcing them into change.

5. Bureaucracy and Injustice

At the heart of all films exploring the modern workplace is bureaucracy. Maddening piles of paperwork. Endless red tape. People whose entire jobs seem to be to avoid being helpful. No discussion of bureaucracy in film would be complete without Orson Welles’ 1962 film The Trial.

- Based on the classic Franz Kafka novel of the same name, the story zeros in on the specific mechanisms of the white-collar workplace that make it so ready for dystopian interpretation.

- Unlike the other works we’ve discussed, the protagonist is an outsider looking into the workplace. One morning K awakes to find himself fighting a legal case in which no one will tell him his crime, and who accuses him.

- He is bounced from one person to another trying to find answers, each more confusing and unhelpful than the last.

- Orwell used huge sets including an abandoned train station to portray the vast scale and complexity of the institution K is up against.

It’s a classic template for the injustice felt by an individual amidst a system. And it can be found in many workplace dystopias, with Severance again serving up the perfect example. Mark S (Adam Scott) doesn’t quite know what injustice he has been dealt. But he knows something fishy is going on. And the plot finds its drive from this quest to work out how exactly his workplace has done him dirty.

6. The Illusion of Freedom

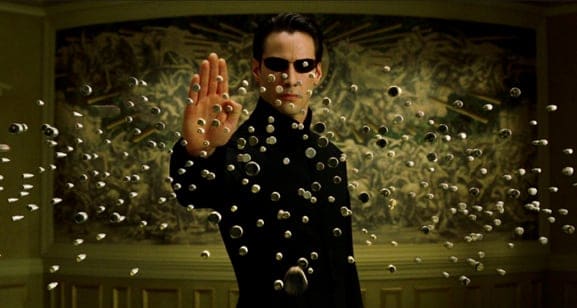

Though also not a traditional workplace dystopia, The Matrix takes the suspicion of bureaucracy and institutions to a new level.

- Neo begins as a skilled hacker and office drone with a suspicion that there may be more to life.

- We soon find out that his grey world of office buildings, drudgery and paperwork is a simulation, keeping human minds distracted with trivial suffering.

- This illusion serves to mask the horrifying truth that all human life is born, lives and dies inside vast energy-harvesting batteries farmed by sentient robots.

In Severance, the bureaucracy is made even more surreal.

- The Macro Data Refiners spend their days looking for “scary” numbers on a computer screen and filing them into boxes, with no clue what the numbers represent.

- This theme of disconnect continues with Lumen’s brutal policy for “innies” who want to leave. They are informed they have the right to send a request to their “outies” to quit. The catch is that because their “outies” feel none of what they experience, they almost never say yes.

This illusion of access to justice strikes the same dystopian tone as The Trial. Ultimately, both workplace dystopias create a sense that there is no escape. And this, in turn, is key in highlighting the oppressiveness and fear that workplace dystopias bear down on the individuals at their heart. Individuality is lost within a system that ultimately aims to clamp down on freedom for most at the expense of those who hold power.

7. Dark Designs: What are the Workers Working For?

So typically where there is a workplace dystopia, you can bet that the corporation at its’ heart has a nefarious, or at least brutally capitalistic goal.

In Severance, the ultimate goal of Lumen is still shrouded in mystery, although there are plenty of fan theories to comb through. Separating workers into distinct selves and then mercilessly abusing one is perhaps disturbing enough. However, some workplace dystopias take this idea further still.

- In Sorry to Bother You (2018), Cassius is unemployed and sleeping in his uncle’s garage. Desperate, he gets a job as a telemarketer.

- With encouragement from a colleague, he uses his “white voice” on the phone to clients. He finds he is talented, and this gives him the ability to extract large amounts of money whilst cold calling.

- He joins a union with his friends, expecting to be fired. Instead, he is promoted to “Power Caller” and invited into a stylish office.

- It turns out that Power Callers secretly sell arms and cheap, essentially slave labor for massive profits.

- Cassius’s greed overrides his morals. He briefly enjoys his new life, but soon finds himself being transformed into a new kind of sellable commodity.

Sorry To Bother You is a workplace dystopia not just about how modern capitalism commodifies people by race, culture or class. It’s also about how we commodify ourselves and our identities, and in doing so, become complicit in our own downfall.

This is one of the most ambitious workplace dystopias ever and demonstrates just how much a workplace dystopia can speak to thematically. When we and Cassius venture outside of the workplace and investigate what lies behind it, the story touches on something profound about the way our society works.

8. The Everyman Hero

Above all, the common thread between each of these films is the protagonist. Each one, from Joseph K in The Trial all the way to Mark S in Severance, is an archetypal “everyman”.

At first glance, there is absolutely nothing special about them, and some are pitifully ordinary. However, they all also learn to show courage in the face of their oppression. Although they are not always successful, this offers the audience a glimmer of hope. We can relate to their ordinary struggles, and more easily connect with their surreal obstacles.

All these ordinary characters go on to do extraordinary things in the name of their freedom and humanity. When this happens, we will them to succeed. Their success gives us hope that we also have the strength to fight ourselves, and escape the tyranny of the 9 to 5.

The “everyman” is the vessel for our own frustration and imagination, showing us the relatable functioning of the workplace and ideally paving the way forward for a less dystopian world.

In Conclusion

Workplace dystopias on film and TV have used the office space to create a sense of dread and hopelessness, and raise questions about modern humanity.

In these worlds, the ideal sold to workers is never the reality. Where technology promises to uplift them, they become invaluable. Where work promises power and wealth, it delivers subservience and spiritual poverty. These films use set, character and plot to portray this in a wide variety of ways. This ranges from surreal visual gags to horrifying existential crises.

The combination of a global pandemic and advances in technology have ushered in another seismic shift in what “work” actually looks like. With more people working from home and AI tools that make our jobs more efficient than ever before, the stage is set for a new representation of the “workplace” on film. One that reflects these changes back to us, and tries to give us a glimpse of what the future might hold.

Whatever this vision is, the key components in making it a persuasive workplace dystopia will likely match those listed above. These are the fundamental keys to making an everyday setting something altogether more compelling, disturbing and revelatory.

– What did you think of this article? Share It, Like It, give it a rating, and let us know your thoughts in the comments box further down…

– Struggling with a script or book? Story analysis is what we do, all day, every day… check out our range of script coverage services for writers & filmmakers.

This article was written by Rebecca Hindmarsh and edited by IS Staff.

Get *ALL* our FREE Resources

Tackle the trickiest areas of screenwriting with our exclusive eBooks. Get all our FREE resources when you join 60,000 filmmakers on our mailing list!

Excellent article by Rebecca! She hit all of the points without adding unnecessary extras! Her article was just what I am looking for (Workplace Dystopia) since I have a new draft in this sub-category!