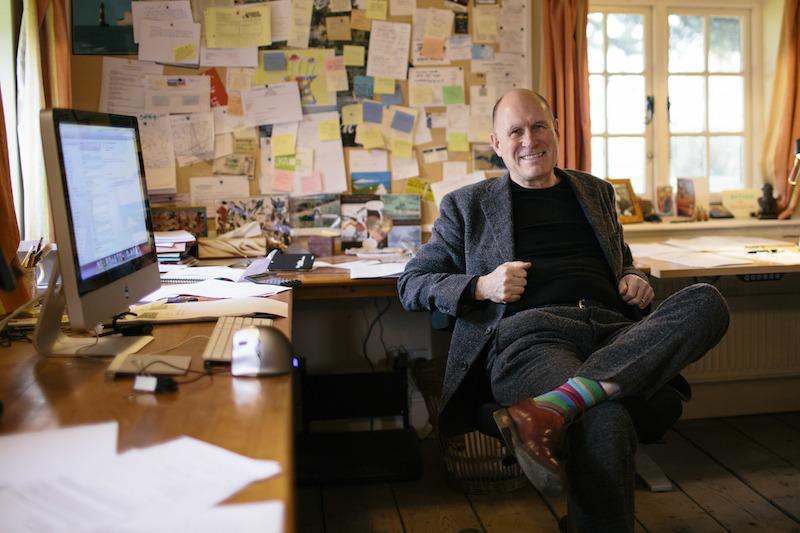

This latest iteration of our long-running Insider Interviews series is with William Nicholson, the prolific screenwriter behind such hits as Gladiator, Shadowlands, Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom and Breathe, amongst many others.

William Nicholson Biography

Though perhaps most known for his work as a screenwriter, William Nicholson is a writer across film, novels, theatre and television. And this breadth was visible right from the start of his career, when he wrote a TV play (Shadowlands), which then became a stage play, which then became an Oscar-nominated film.

In addition to his stage, film and TV work, he is also a prolific novelist, most notably in the fantasy genre, with his Wind on Fire and Noble Warriors trilogy.

But it is screenwriting where William Nicholson has his most notable credits. He’s been twice Oscar-nominated and has also worked as a writer-director on a number of occasions. Moreover, he has written screenplays for some of the biggest directors in Hollywood, such as Jerry Zucker, Ridley Scott, Tom Hooper, Angelina Jolie and Ron Howard.

So we sat down to talk with him about why he loves screenwriting compared to other mediums, his writing routine and his excitement at the future for young writers.

William Nicholson – Selected Screenplays:

- Shadowlands

- First Knight

- Firelight (also director)

- Grey Owl

- Gladiator

- Elizabeth: The Golden Age

- Les Miserables

- Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom

- Unbroken

- Everest

- Breathe

- Hope Gap (also director)

- Thirteen Lives

Interview with William Nicholson

What has your path been and how did you get started in the industry?

WILLIAM NICHOLSON:

“Well, I didn’t intend to become a screenwriter, I intended to become a novelist. And I tried very hard to be a novelist. I wrote eight novels, all of which were turned down.

But you can’t make a living on rejected novels, so I had a day job at the BBC.

While I was at the BBC, my colleagues became aware that I got up early in the morning to write. I was doing up to three hours of work in the early morning before going into my day job as a documentary filmmaker. I was a very modest kind of documentary filmmaker – we were making half-hour programmes once a week.

So one day one of my colleagues asked if I would help out with a project that needed a writer. But they had no money to pay a writer so he asked if I would do it for free. And I was kind of intrigued. That was to be about Martin Luther the heretic, the religious reformer. So I fairly quickly wrote a script for these friends. And to my surprise, it was quite good.

I think what had happened was that my novels, over which I laboured mightily for years, were too constipated. I was trying too hard, I was trying to impress too much. With this quick script, it was a 60-minute drama. I didn’t, in a sense, take it too seriously. But I guess I’d learned quite a lot by then about writing. And it worked.

Also, I was working with other people who would read it and say, “Well, you know, hang on, it doesn’t work. How about changing it?” So the preciousness and the pretentiousness with which I approached my novels was not present. And the results were much better. This was a shock to me.

The script attracted Jonathan Price to play the lead part. It was made and it was modestly successful; Martin Luther, Heretic. My friends then said, “Well, let’s do this again”. We were all full-time documentary makers, none of us were in the drama area. But we all wanted to do other things; I wanted to be a writer, one friend wanted to be a drama director, one friend wanted to be a drama producer. So they said, “Let’s do another one”.

They came up with a story about the children’s writer CS Lewis. At first, I wasn’t very keen. But as I looked at the story, I began to connect to it. So I said, “Okay, I’ll give it a go”. And really fast, in like three weeks, I wrote a script called Shadowlands. That was made as a TV film with Claire Bloom and Joss Ackland and won the BAFTA Best Television of the Year award.

I was launched, from then on. People wanted me to write scripts for them. And I discovered that I had a talent for it. I was, in a sense, saved from my own worst faults by working with other people. So that’s how I got started.

That TV version, by the way, then became a stage play, which won the best play of the year award. Then it became a movie script, which got an Oscar nomination for best screenplay. So I really was launched by that.”

What is your most formative cinematic, or television, experience? When did you know you had to make this your life?

WILLIAM NICHOLSON:

“The answer is I did not know it, and I still don’t know it. I’ve never intended to make screenwriting my life. Since becoming successful as a screenwriter, I’ve written children’s novels and adult novels, which I love. I keep coming back to screenplays because I do it better, to be honest. And because I like the collegiate nature of the work.

It’s embarrassing to admit it, but I was not raised on film and television. I mean, I can remember liking and watching children’s television when I was little and I’ve always liked the big science-fiction movies. But I’ve never been a film buff or a film lover. So I’m a bit of a fraud really.”

What is a piece of advice you don’t hear enough that you feel is helpful for screenwriters just starting out?

WILLIAM NICHOLSON:

“Quite a lot here. I would say, first of all, you have to have a particular personality to cope with screenwriting.

The problem with screenwriting is other people think they own you and know better than you and can rewrite everything you do and sack you. Generally, they do not treat you with the respect that you wish, the respect that you would get if you were a playwright or a director. You are a tool for other people.

This is very annoying and distressing, and at times extremely painful. So if you’re going to go into the business of writing screenplays, you have to have a pretty well-armoured ego. Either that or you have to have a kind of Zen ability to let your ego go. So that when you sweat over a script or a draft and you send it in and they say, “It doesn’t work, we don’t like it”, you don’t kill yourself. And I think that’s hard. But it’s going to happen.

It is not a walk in the park. To be a successful screenwriter, you have to have enormous resilience. I think I’ve achieved this because I have a very bad memory. I’ll write a draft and I’ll send it off, and I always work faster than they do. So sometimes weeks go by and then back comes the answer: “We don’t like it. It’s got to be changed”. By that time I’ve almost forgotten what I wrote. They tell me what the problem is and I then buckle down and it’s as if I’m doing something new.

I think that’s helped me a lot, sort of being a goldfish. If you cling to what you’ve done, you will be tortured, you will suffer the death of 1000 cuts.

It is not a walk in the park. To be a successful screenwriter, you have to have enormous resilience.

It’s a very tough game. The only way not to make it tough is to be a writer-director. Then you control your own material. And I urge you to do that, I strongly recommend it.

There is one snag. This horrifying existence, that I’ve led of having everything I do messed about with, has kept me humble. It’s made me aware all the time that I can always do better. Because the criticisms I get are from people who aren’t fools. These are people with very smart responses. And it shames me to discover that I hadn’t thought of the things I’m told. But there you go. I take advantage of it and I do it.

I’ve twice made films as a director. If I have total control, that process doesn’t happen. I suspect to the detriment of the finished work.”

What’s the biggest thing you’ve learnt in your career as a writer so far? Something you wish you’d known when starting out.

WILLIAM NICHOLSON:

“I wish I’d known that however successful you are, with every script you’re starting again at the beginning. There is no place of safety. You’re always on the cusp of failure. So long as you kind of assume that, then you say to yourself, “I’m lucky to be commissioned” (if you have been commissioned), “I’m lucky to earn some money here. I’m excited by what I’m doing. But maybe it’ll all go nowhere”.

As you know, many screenwriters have written many screenplays that have never been filmed. So I think begin with that expectation and then forget it. Think that everything you do is going to be a masterpiece and pour your whole soul into it. Then let it go.”

What’s the most useful piece of advice you’ve found from a craft perspective? Something that was a fundamental shift in your writing process.

WILLIAM NICHOLSON:

“My writing process has stayed pretty much the same all the way through, and it’s not everybody’s. The way I work and the advice I would give is: work fast, work dirty and share what you have done.

The alternative is you agonise over a draft for nine months or over a year, and then you finally release it. And if they don’t like it, you kill yourself.

What I would much rather do is work as fast as I can, deliver a draft quickly – I can do it in three to six weeks – knowing that you’ve got a long way to go. Because that way your colleagues become involved at that stage and as they make their comments and you do the next draft, they’re on board with you. If you leave it for a very long time and they’re not on board with you, they’re probably going to sack you and move on.

So I think my method, which is multiple drafts willingly offered, works very well. I find it always gets better even in tiny ways, even if what you’re being asked to do isn’t because it’ll be better but because it works with that director or works with that actor or for that location. I’ve had lots of scripts where I’ve been told, “We can’t do it on a clifftop, can we do it in a bathroom?” And I say, “Yeah, sure”

I personally – and this, you’ll find archaic – handwrite my work. It proceeds at the pace that I create. When I’ve handwritten the first draft, I type it out into Final Draft, and print out that copy and then handwrite changes into it, type those in, and so on. I like that. But you probably think I’m mad!”

What does your daily writing routine look like?

WILLIAM NICHOLSON:

“Again, everybody’s different. I’m an early morning person, I get up before six in the morning. I have a cup of coffee. I have a little think about what I’m about to work on. Then, crucially, I go for a walk. I walk from my house up to the village and collect the newspaper. It’s a circular walk and back, which takes about 45 minutes.

On that walk; everything happens.

Whatever I need for the next stage of what I’m writing comes into my head. It’s like magic. All the knotty puzzles I left the previous day are resolved. Whole new ideas pop up. I suppose it’s because I’m fresh and I’ve had my cup of coffee and I’m walking. Sometimes in quite unpleasant circumstances.

I don’t do it every day but I try to do it in all weathers, because it delivers. So I’m back at my kitchen by about seven, where I have some breakfast. Then by about half-past seven, I’m out in my office, which is in an old garage. And I’m at work. I have a break around eleven just to break things up – go inside, make a cup of tea, talk to Virginia (my wife). She’s working as well, we exchange what we’re up to and I go back out with my cup of tea and carry on working.

So that takes me till about one o’clock. I have lunch and then I’m shattered! I lie down on a sofa and listen to music. But I don’t really do any work for the rest of the day. Unless I’m under a lot of pressure.”

You’ve worked on several historical, period pieces? How do you approach getting into such vast contexts?

WILLIAM NICHOLSON:

“The answer, of course, is research. I do love research. I love stumbling upon strange little details and thinking, “Yeah, that’ll make a scene, that’ll be wonderful”. So I do research a lot. I read a lot. I take notes as I read all the bits that I think I’ll want. So I’ve then got them spread out in front of me.

But I do something else as well; even though it’s historical, I’m really writing about now. I’m writing about people now…just in fancy dress. I don’t bother about anachronisms or anything like that. The thing has got to live for an audience now.

To give you a little specific example of how that works; my characters in historical movies never speak as if they are out of a book. They do not say, “Sire, the day has not yet dawned when you will be deposed”. They say, “The day hasn’t yet dawned when you’ll be deposed”. Because that’s how we talk.

I use, not slang, but demotic speech. I personally believe that even in the past, people did this. The only reason anybody thinks that they spoke like that in Jane Austen is because Jane Austen was writing a book. If you had gone to Jane Austen, she wouldn’t have said, “It is not what I would have wished”. She’d say, “It isn’t what I would have wished.”

So I think you have to be quite ruthless about that. The other point about research and historical events is how faithful do you have to be? And I think the answer is broadly faithful. But I do a lot of inventing because I want it to come to life.”

You’ve written across film, theatre and novels – what are the biggest differences in how you approach each form? And which is the most enjoyable to write?

WILLIAM NICHOLSON:

“They’re all so different. I think I would honestly say I like theatre best. It’s the area I have worked in the least. Because I find it quite difficult to come up with something and get it produced. I love it because it’s a real writer’s medium, but it has actors and directors to add to what I do. That’s my favourite, though it’s probably my least successful.

I love novels because you can go inside people’s experiences in a way that you can’t in film. It’s the medium for understanding the psychology of people. I’ve loved writing novels. I’m not writing novels at present, because my novels have not been particularly successful.

So it’s back to screenplays for films. And I do love that. It just gives me constant joy. I’ve reached a point now where I do get asked to do a lot. So that’s wonderful. And I think I can do it well, which I like. I’m constantly learning. Every project that’s thrown at me is a whole new area of discovery for me. So I enjoy that very much as well.

And a novel takes me a year, whereas a screenplay takes me five or six weeks, the first draft at least. I’ll be on a project probably for two years overall.”

What movies and/or TV series have you enjoyed recently and why?

WILLIAM NICHOLSON:

“Well, I’ll be very obvious here. I am a huge admirer of Succession. Then I always watch the very imaginative Sci-Fi series. A little while ago, there was a weird version of Watchmen done by Damon Lindelof, which I was incredibly impressed by. I liked Dune recently, even though it was a little bit slow.

I’m currently watching Foundation, which is a bit of a mess. I’m a great admirer of the books, but it’s all so ambitious and it looks so great. It’s a wonderful bit of design. As you can tell, I like films that play with ideas.

I also like films that are very successfully moving emotionally, but there are very few of them. Most of the so-called emotional films are fake, with unearned emotion.

I binged on Couples Therapy recently. I liked Cyrano, I thought it was very, very successful. I’ve been pretty disappointed by most of the other recent films, to be honest with you.”

What does the future of the industry look like to you? What is changing in film & TV and how is the industry reacting to it?

WILLIAM NICHOLSON:

“I mean, the future is fantastic. It’s just terrific. The whole thing’s exploding. There’s so much demand. So many outlets wanting what they call ‘content’. That’s very, very exciting.

I mean, my time in it is probably passing. I’m 74 now and I can’t go on forever. Well, I will go on forever, but they’ll stop wanting what I do after a certain time.

I mean, the future is fantastic. It’s just terrific. The whole thing’s exploding. There’s so much demand.

How is it changing? The huge change obviously is the new respect given to long-form television, which I love and am wanting to move into and am making moves to do so. Because it seems to me I can bring together novel writing and screenwriting in one form.

I personally love something that goes on for a long time and is good enough. Usually, it fizzles out, I’m afraid they can’t sustain their plot or their characters. But sometimes they do and then it’s just so exciting.

How is the industry reacting to it? Well as we know, we have a crisis of crews of tech, which I’m very aware of. And I suppose because of the new demand, lots more people will be trained. I hope so. But also, what’s so exciting is there are so many young writer-directors being given a chance that it’s created a feeling that young writer-directors are hot. And that is simply brilliant.

Sex Education, Fleabag, I May Destroy You – all these really brilliant pieces of work, it’s just so exciting. So I think we’re in a golden age, I really do. I’m so pleased to have lived to see it and to be around to enjoy it. And I hope to contribute a little bit to it before I pop my clogs. So I’m very, very, very hopeful.”

Thanks William!

- View all previous Insider Interviews, here.

- What did you think of this article? Share It, Like It, give it a rating, and let us know your thoughts in the comments box further down…

- Struggling with a script or book? Story analysis is what we do, all day, every day… check out our range of script coverage services for writers & filmmakers.

Get *ALL* our FREE Resources

Tackle the trickiest areas of screenwriting with our exclusive eBooks. Get all our FREE resources when you join 60,000 filmmakers on our mailing list!