What is Narrative Structure?

What is Circular Storytelling?

In a circular narrative, the story ends where it began. Although the starting and ending points are the same, the character(s) undergo a transformation, affected by the story’s events.

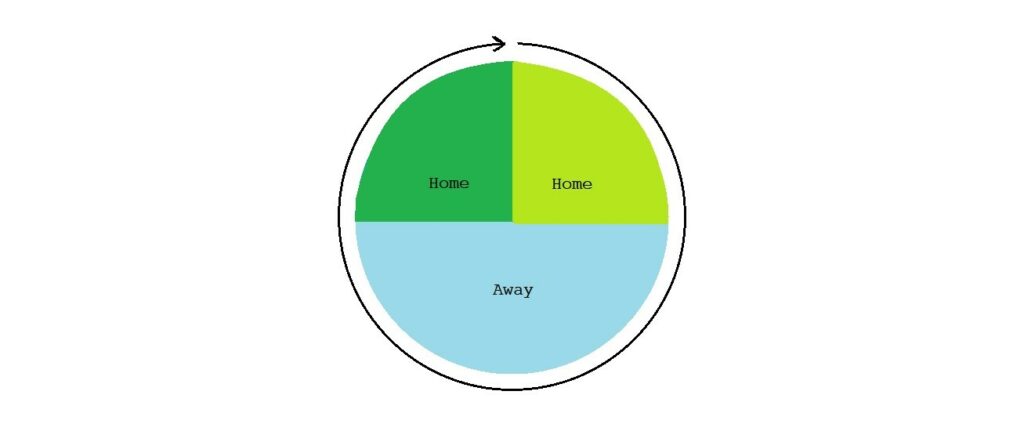

One way to visualize the circular storytelling structure is with a diagram:

- Home: the character and their world are introduced.

- Away: characters pass into another world “away from home”.

- Home: they return home, changed by their experience.

This demonstrates how the story is primarily about venturing to the “away” part of the story, in order to then return home carrying what they have learnt from this time “away”. The story is bookended in this regard, highlighting the disruption to the character’s normal, everyday life that storytelling always relies upon.

What’s the Point of Circular Storytelling?

By using a cyclical structure, writers can emphasize the knowledge gained during the course of the story.

The audience can compare a character’s behaviour in the first and last scenes (and it makes for an even easier comparison if the scene is essentially the same) making the character’s journey clear as day.

So circular narratives highlight in no uncertain terms your character’s progress.

Gone Girl, for example, both opens and closes with the above shot of Amy Dunne (Rosamund Pike), lying on her husband Nick’s chest.

- The shots are almost identical at the opening and closing of the movie. And yet we the audience know so much more about their relationship between them.

- At the end of the movie, Amy and Nick return to a life of secrets. However, rather than the secrets being kept between themselves, they’re kept from the outside world.

This is a great example of circular storytelling as the characters (and the audience) return to where they started but do so completely changed. Moreover, it’s borne out in the plot, narrative arc and visuals, making for compelling and satisfying viewing.

Circular Storytelling in Other Mediums

Whilst often used in cinema, circular storytelling is also frequently present in other literary and artistic forms. And it can be helpful to analyze these forms to show the true essence of what circular storytelling is really about.

Essays, for example, typically use circular structures.

- The introduction and conclusion often mirror each other.

- However, the information presented before the conclusion ‘changes’ the deductions of the writer.

Poetry also often utilizes a circular structure.

- The first and last stanzas are often similar, mirroring each other in some way.

- For example, John Keats’ ballad La Belle Dame Sans Merci begins and ends with similar language.

Music, too, often uses a circular structure.

- Just to pick one example, Elvis Presley’s In The Ghetto opens and closes with five similar lines.

- The song, therefore, is a journey based around a refrain that the singer comes back to.

Novels (these examples all have film adaptions, too) regularly use circular storytelling.

Alice In Wonderland by Lewis Carroll and The Chronicles of Narnia by C.S. Lewis are classic examples.

- Alice’s adventures in Wonderland are shelved neatly between the bookends of Alice’s real life on the river bank.

- The Chronicles of Narnia, meanwhile, begins and ends with the children in their original, “normal” world after having explored Narnia.

Both examples show the characters exploring a vast fantasy world and then returning to their everyday reality completely changed. In these instances, the characters need this change and the “away” part of the story provides them with it.

- In Alice in Wonderland, Alice is bored in her daily life.

- Whilst in The Chronicles of Narnia, in the context of the Second World War the children need an escape from the precarious temporary life they are living sheltering from the war.

The Hero’s Journey

Circular narratives overlap with other structures. And it’s helpful to understand these structures for a full and cohesive picture of what circular storytelling is really about and what it entails.

The Hero’s Journey structure, for example, is the most popular story structure in the western world. And it’s helpful to remember when considering circular storytelling as it often pertains to the kind of journey the protagonist will go on. It’s inspired by the work of mythologist Joseph Campbell and redefined by Christopher Vogler in The Writer’s Journey.

The 12 stages include:

- The Ordinary World: The hero’s everyday life is established. The hero is oblivious of the adventure to come.

- The Call to Adventure: Our hero receives a call to action. This may not literally be an epic call to adventure but whatever it is disrupts the hero’s ordinary world.

- Refusal of the Call: The reluctant hero has fears and personal doubts causing them to resist their adventure.

- Meeting The Mentor: A teacher arrives, providing them with some skill, tool or courage enough to start the journey.

Leaving Home…

- Crossing The First Threshold: The hero leaves home, entering the new world, “away”. They commit to their journey.

- Tests, Allies, Enemies: The hero faces increasingly tough obstacles that test their character on their journey.

- Approach to the Innermost Cave: The hero faces a terrible danger or inner conflict. They make their final preparations to face their biggest challenge yet, and probably have some personal doubts resurfacing.

- The Ordeal: The hero must face their most dangerous test. It will require all of their skills and experiences to overcome. If they fail they will die, or life will change forever.

- Reward (Seizing the Sword): After defeating their enemy, the hero emerges victorious, often with a prize, some insight, a power or reconciliation with a loved one/ally. But their journey isn’t over yet.

Returning Home…

- The Road Back: The hero must return home, often having to choose between his life at home or “the higher cause”.

- Resurrection: The hero must have their most dangerous encounter yet. The consequences of this battle will reach the lives of the people he left behind. Ultimately, the hero will succeed and emerge reborn.

- Return with the Elixir: The hero returns to the ordinary world a changed person, with a new perspective. They are back where they started, but life will never be the same again.

The Hero’s Journey chimes with circular storytelling because the first and last three stages are set in the hero’s ordinary world – home. If you were to use this structure when telling your circular story, there would be plenty of time, for example, for you to see the change in the hero after their quest.

Circular Storytelling in Dan Harmon’s Story Circle

Dan Harmon became famous for co-creating the sci-fi comedy series Rick and Morty using a “story circle” technique he created when adapting The Hero’s Journey for use in TV.

Harmon believes that “the REAL structure of any good story is simply circular – a descent into the unknown and eventual return”.

Harmon uses these 8 stages in each episode of Rick and Morty:

- The character is in a comfort zone (status quo)

- They want something (often brought about by the inciting incident)

- They enter an unfamiliar situation (must do something new in the face of what they want)

- The character adapts to it, faces a challenge, struggles….and then begins to succeed

- The character gets what they wanted – usually a false victory

- They pay a heavy price for it – they realize what they wanted wasn’t what they needed

- The character returns to a familiar situation armed with the new truth

- They have changed for better or worse

For more detail on this structure, check out our in-depth article looking at Dan Harmon’s story circle.

Circular Storytelling in Sitcoms

Harmon’s structure is another great example of how to use circular storytelling. Rick’s experience of “home” bookends his adventure “away”, making his arc, and what he has learned during the course of the story, crystal clear for the audience.

- The story circle suits the 23-minute (or so) sitcom as a character doesn’t need to undergo life-changing transformations like in a feature film.

- For a story to continue for multiple seasons, characters can’t completely transform at the end of every episode. That would be exhausting.

- However, they can learn small truths about themselves and the story world as the series progresses.

It’s a great way of allowing characters (and the audience) to experience a new set of circumstances and learn something along the way, all whilst retaining the familiar elements which keep us coming back, week after week, episode after episode.

Now, when writing, Harmon says

I can’t not see that circle. It’s tattooed on my brain.

Dan Harmon

Determining the Best Narrative Structure For Your Screenplay

How can you tell if a circular structure is right for you? Well, these are some important questions to ask yourself when discerning what structure is best for your story…

- What’s the narrative point of view? Is it an omniscient narrator or a first-person narrative?

- Are there multiple points of view through the eyes of different characters?

- How many perspectives does the script feature?

If you have multiple characters and parallel storylines/timelines, for instance, circular storytelling might not be right for this particular story. This is because it’ll be difficult to reconvene all your characters and separate narratives in the same place at the end. It’s certainly not impossible (often with multiple characters this will occur when they’re in a group) but it is difficult.

So…

- What is the protagonist’s character arc?

- What change will they undergo?

- What series of events will make that possible?

You want to consider if your protagonist’s change is best emphasized when compared to their previous life. Your change might be better illustrated, for example, with them moving onto a new life entirely. Maybe the story is about leaving something, somewhere or someone behind.

So…

- What are the major events in the story? Identify your starting point, inciting incident, rising action, turning points, climax, falling action and final resolution. These points anchor your story.

- In the plot you currently have, do your characters naturally come back to where they started?

When using circular storytelling, characters must come back to where they began in some way. The structure emphasizes characters venturing out to get what they need and then returning, having changed, but back exactly where they started literally speaking. If you find your character venturing somewhere new entirely, this isn’t really circular storytelling, despite perhaps potentially sharing some of the characteristics.

Is Circular Storytelling Right for Your Story?

Circular storytelling only works if the story you want to tell fits into it. Remember that content dictates form, so don’t worry if your story isn’t a circle.

- Quentin Tarantino acknowledged that his non-linear approach to structuring Pulp Fiction, for instance, doesn’t always work because it can be more impactful to just tell a linear story.

- It’s all about what message you are seeking to get across with your story and how the protagonist’s journey reflects that message.

There are plenty of other forms and structures your story can take. And determining which is best for your story is about understanding your story’s true essence and what you are trying to say with it. If you don’t understand this then you will probably struggle to instinctively know what structure is best for your story.

Finding the right structure, much like the hero’s journey, is about discovery. But regardless of whether you strictly use the circular storytelling structure or not, it can be a useful tool to sharpen your protagonist‘s arc with.

All stories, after all, take their protagonist on a journey. So understanding exactly how that journey relates to change in the character, from the start to the finish, can be vital in making it compelling and meaningful.

For references on other structures, check out our articles on linear storytelling and nonlinear narrative.

–What did you think of this article? Share It, Like It, give it a rating, and let us know your thoughts in the comments box further down…

– Struggling with a script or book? Story analysis is what we do, all day, every day… check out our range of script coverage services for writers & filmmakers.

This article was written by Lyra Fewins and edited by IS staff.

Get *ALL* our FREE Resources

Tackle the trickiest areas of screenwriting with our exclusive eBooks. Get all our FREE resources when you join 60,000 filmmakers on our mailing list!

I love this article, especially since I believe my book that I’m finishing up is like this. It starts and ends with the same question. Both the intro and the last chapter start with the same question.