Writing Science Fiction Screenplays

Sci-Fi is one of those odd genres – like the Western – that among script theorists often stimulates more argument about ‘defining your terms’ than it does about structure, plot or theme.

It is helpful first to qualify the term ‘genre’, as film theorists and script analysts have differing – though not mutually exclusive – meanings for the word. So let’s look at those as the starting point for writing Science Fiction scripts.

FILM GENRE AND STORY GENRE

In film theory, the Science Fiction genre is evidenced by the portrayal of a future or parallel world and the presence of a very definite set of themes, tropes, ideas and meanings. In story analysis, Sci-Fi is a setting, like the Wild West of the Western, not a genre in its own right. So we could say that Sci-Fi is a ‘film’ genre but is not a ‘story’ genre; rather, it is a story setting.

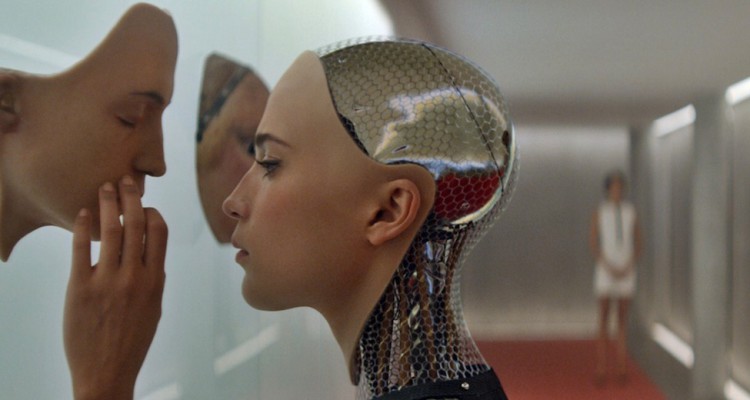

There are plenty of examples to support either position. Films such as 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY, SOLARIS, GATTACA, INTERSTELLAR and EX MACHINA are instantly classifiable as belonging to a single, unifying film genre.

On the other hand, films like STAR WARS (the Hero’s Journey in space), SOLDIER (SHANE in space), OUTLAND (HIGH NOON in space), ALIEN (THE THING in space), BATTLE BEYOND THE STARS (THE MAGNIFICENT SEVEN in space), LOST IN SPACE (SWISS FAMILY ROBINSON in space) or even BLADE RUNNER (THE BIG SLEEP in a speculative future?) and DREDD (TRAINING DAY in a speculative future?) obviously belong to different story genres but all take place in a Sci-Fi setting.

“Two possibilities exist: either we are alone in the Universe or we are not. Both are equally terrifying.”

So said Arthur C. Clarke, neatly encapsulating both types of Science-Fiction setting, because Sci-Fi is the arena in which we confront both the ‘lonely’ and the ‘crowded’ possible futures and explore how we could live in them.

Writing Science Fiction leads us to confront parallel presents and alternate pasts, which are themselves speculative futures of their own ‘establishing present’ or ‘temporal bifurcation point’ (both THE MAN IN THE HIGH CASTLE and FATHERLAND are set in speculative futures with an establishing present of WWII).

Indeed, Sci-Fi is the genre is which a story can start with the proposition ‘we are not alone’ and end with the proposition ‘we are indeed alone’, this reversal being at the core of ‘the aliens are us/we are the aliens’ stories like THE 4400 and PROMETHEUS.

This is the crux of the Sci-Fi genre: science is the engine of morality. Science demands that we think about and evaluate supremely difficult moral choices.

When writing Science Fiction, you can take any ‘story’ genre or combination of ‘story’ genres, for instance: a fish-out-of-water ensemble comedy with a classic redemption arc for the lead protagonist, and set it in space, for example GALAXY QUEST (one of the cleverest, funniest and most elegantly-structured Sci-Fi scripts of the past twenty years).

This confusion over genre partly stems from the fact that once you choose to play out a story in a Sci-Fi setting, you can’t help but take on many of the themes and tropes that together define the Sci-Fi ‘film’ genre.

ALIEN deals with ideas about fertility, reproduction and evolution that are wholly absent from the Horror ‘story’ genre to which the screenplay nominally belongs. Even though ostensibly a noir detective story (especially in its original theatrical version with world-weary Voice-Over) BLADE RUNNER confronts the key Sci-Fi themes head on.

LOST IN SPACE and GALAXY QUEST end up demanding the kind of difficult moral choices of their characters that can only exist in a world where the boundaries of science have been pushed back to the very edges of the known universe. This is the crux of the Sci-Fi genre: science is the engine of morality. Science demands that we think about and evaluate supremely difficult moral choices.

Perhaps the clearest way to demonstrate how Sci-Fi infuses any ‘story’ genre or narrative thrown at it, is to take a quick look at comedy films in the ‘story’ genre that have a Sci-Fi setting. The best Sci-Fi comedies are those that fulfil the philosophical dictates of the ‘film’ genre. MEN IN BLACK and GALAXY QUEST may contain comic narratives but they also deal with difficult moral choices that have galactic consequences.

A moral choice in a boilerplate Comedy Drama will affect the protagonist and his immediate family, friends and colleagues. A moral choice in a Sci-Fi Comedy (or in any other ‘story’ genre competently played out against a Sci-Fi setting) will affect entire worlds, solar systems or universes.

There are no better examples of this than the galaxy carried on the collar of Orion the cat in MEN IN BLACK, or the ‘Omega 13’ device in GALAXY QUEST. Along with scale, the other element of immediate interest to screenwriters is temporal relativity. In Sci-Fi you can do things with time that open up a myriad of possibilities for storytelling and innovative structure.

UTOPIA, DYSTOPIA AND FANTASY

Sci-Fi is the only genre, apart from the Western, still to resist the post-modern impulse. This could be due to the fact that Sci-Fi is not a genre at all, but the actual reason that Sci-Fi so completely resists the post-modern relativity of time and meaning is because that is what it was always about in the first place. There are no realities or meanings more relative than those revealed by Science Fiction.

In its purest form, the Sci-Fi narrative presents a polarity of moral choices and asks the most difficult of existential questions. This polarity is encapsulated by the utopian (ordered, no conflict, boring) and the dystopian (messy, intriguing, human).

LOGAN’S RUN is the best example in terms of story theory because although the action begins in a utopia, we soon realise that in fact we are in a dystopian nightmare (the Act One reversal). Films like BRAZIL, DARK CITY and THE MATRIX may start with a semblance of reality (the world as you just about know it) but then fairly swiftly make us aware that we are actually in a version of hell (or rather an allegory of the world as it really is).

Across the films and the television show and its spin-offs, the STAR TREK franchise has over many years dealt with a plethora of moral conundrums, philosophical debates and existential questions. In particular, the films have often addressed ideas about existence and consciousness that are right at the frontiers of human thought. STAR TREK: THE MOTION PICTURE, like 2001 (and its parody DARK STAR), asks what would happen if a computer gained consciousness or decided to play God.

Although the action begins in a utopia, we soon realise that in fact we are in a dystopian nightmare.

The way in which a Sci-Fi trope (alien intelligence personifies a lost love) leads to the kind of emotive drama that Soderbergh chose to foreground in his version of Stanislaw Lem’s Solaris, is reminiscent of countless episodes of THE NEXT GENERATION and VOYAGER. STAR TREK IV: THE VOYAGE HOME – inspired like ALTERED STATES and THE DAY OF THE DOLPHIN by the ideas of futurist and consciousness researcher John C Lilly – asks some probing questions about exactly what we are doing to our planet and our co-inhabitants with our technological hardware (Lilly christened this the ‘Solid State Conspiracy’).

The sequence of STAR TREK films is also interesting for the inclusion of narratives that belong to individual story genres: STAR TREK III: THE SEARCH FOR SPOCK is a Quest Narrative; STAR TREK VI: THE UNDISCOVERED COUNTRY is a Political Thriller.

Sci-Fi also has a fantastical quality that stems directly from the otherness of imagined worlds. This is more often seen in films that – at least in their original conception – use Sci-Fi as a setting, as these films often play out mythic ‘story’ genre narratives.

Films like DUNE and the STAR WARS movies portray epic, archetypal dramas against the backdrop of a fully-imagined world, be it future, past or present. In setting, these are a hybrid of Sci-Fi and Fantasy. (When THE LORD OF THE RINGS was still only a twinkle in Peter Jackson’s eye, George Lucas gave us the mythic fantasy WILLOW, a film that Chris Vogler describes as a perfect example of what happens when you try systematically to hit every beat of the Hero’s Journey without spin, skew or innovation.)

Any fans of Starz’s brilliant comedy series PARTY DOWN will remember a particular moment of highly pointed differentiation between ‘Sci-Fi’ and ‘Fantasy’, which skewered a debate that will in no way be resolved here.

Dick’s novels and short stories have for years been among some of the hottest properties in Hollywood.

It is no coincidence that some of the greatest of all Sci-Fi films have been adaptations of novels because the kind of complexity of thought, depth of theme and richness of setting that come with the novel are rare in original screenplays.

If you are writing Science Fiction, take a look at the work of Ray Bradbury and Philip K Dick, who are perennial favourites of film-makers. Dick’s novels and short stories have for years been among some of the hottest properties in Hollywood with Amazon’s TV series THE MAN IN THE HIGH CASTLE merely the latest in a long sequence of adaptations.

SCIENCE FACT AND SCIENCE FICTION

Every time there is a significant scientific advance, a new branch of moral philosophy is born. Any writer worth their salt cannot help but want to grapple with the social, cultural and emotional fall-out from a major scientific or technological breakthrough or theory (or failing that, use it as grist to the genre mill).

Some examples of this: state control through technology (1984, or as allegory in THE MATRIX), cryogenics (SLEEPER, DEMOLITION MAN), cloning (MULTIPLICITY, THE 6th DAY), state control of fertility (THE HANDMAID’S TALE, SUPERNOVA), memory recording and exchange (TOTAL RECALL, STRANGE DAYS, UNFORGETTABLE), and cybernetics (THE TERMINATOR, BICENTENNIAL MAN, A.I. ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE).

Sci-Fi is the arena in which we confront possible futures (and, indeed, alternate pasts) and explore how we could live in them.

Sci-Fi films continue to reflect advancements in science and our thinking about the consequences of ‘progress’, from films about computers developing consciousness and will (2001), to films about artificial intelligences developing souls (A.I.) and from a film in which a replicant thinks he is human (BLADE RUNNER) to a film in which a human discovers he is a clone (THE 6TH DAY).

When writing Science Fiction, remember this is a genre that can question the meaning of life head-on. Sci-Fi can also deal with a specific scientific advance or theory and its ramifications, or rub off on whichever ‘story’ genre or library film re-make you care to place within it.

Sometimes it will do all three: THE MATRIX trilogy applies the particular theoretical science of cyberspace, takes on the mythological ‘story’ genre of the chosen saviour and dares to ask fundamental philosophical questions. Why are we here? What is reality? What is freedom? And most crucially: what makes us human?

This year scientists revealed a map of the epigenome, the genetic switches that activate or inhibit different parts of our DNA. What more could any writer need as inspiration?

Written by Nic Ransome. Copyright Industrial Scripts 2015, All Rights Reserved.

– What did you think of this article? Share It, Like It, give it a rating, and let us know your thoughts in the comments box further down…

– Struggling with a screenplay or book? Story analysis is what we do, all day, every day… check out our range of services for writers & filmmakers here.

Get *ALL* our FREE Resources

Tackle the trickiest areas of screenwriting with our exclusive eBooks. Get all our FREE resources when you join 60,000 filmmakers on our mailing list!

When you’ve got an in idea your head, and you need to tell the story, where do you begin? Use this advice to write a science fiction novel.

Science fiction is not just about aliens, mermaids, time travel, and more. Here, you can also write about deep and philosophical stuff, and even tackle societal issues. For example, issues on technological advancement such as the possible takeover of robots and the impending destruction of the planet are commonly emphasized in numerous science fiction novels. These and all the other issues in the society today are tackled in length in science fiction because there is no better place to explore them than in this genre.

Very well said!