Writing a sidekick character can come with a lot of creative freedom. Where your protagonist or hero may have a rigid characterisation, a sidekick can complement them in many different ways. Are they a life-long friend, a reluctant ally, or even an animal?

As the name suggests, their main role is to assist the protagonist (or perhaps antagonist). As such, a sidekick can be equally as crucial to story development as those that they accompany.

Despite not being at the center of the story, they often have an important role that can’t be filled by the hero. This could be as much as having a power that the protagonist doesn’t. Or it could simply be bringing some comedy and lightheartedness to the script. A sidekick can exist in any genre as long as they are a close companion to the protagonist.

So let’s discuss the key aspects to consider when writing a sidekick character. We’ll also look at some traditional examples seen in cinema.

Table of Contents

Why Have a Sidekick Character?

A sidekick is a specific role different to a secondary character. They can be another protagonist or a supporting character. Either way, they are easily identifiable through their relationship with a particular character.

The key question to first ask yourself is does your story need a sidekick? Make sure it’s appropriate, justified, and clearly adds something to your film.

A common reason to have a sidekick is to have someone for the protagonist to voice their thoughts to. This way, there is no need for monologues or internal dialogue.

This allows them to be a link between the audience and the main character as they supply information that allows the audience to understand the nuances of the protagonist and the plot.

- For example, Dr John Watson brings the audience into Sherlock Holmes’ world and questions all his deductions on the audience’s behalf.

Of course, it’s not justified to have a sidekick purely asking questions and rambling off exposition. They are also there to elevate the protagonist. This could be by helping them or acting as their foil.

So think carefully about whether your protagonist needs someone to play off of or if they work better alone. The sidekick character must be something that adds to the story itself and not just smooths its execution.

The Sidekick Character As Their Own Person

It’s important when writing a sidekick that they are not simply an add-on to your main character. They need to be just as equally crafted as any other character, especially considering they will most likely have a lot of screen time.

A sidekick can be dynamic or static.

- A dynamic sidekick will, like the protagonist, grow and change throughout the story and potentially become more relevant as the story progresses.

- A static sidekick will see no significant change throughout the film. Rather, they will encourage it in the protagonist. Their consistent personality and function will highlight the evolution of the protagonist.

Neither one is right or wrong. It’s just important to write your sidekick in a way that works best for your film.

- It may give your film more depth if the sidekick is just as complex as the hero. This is especially true if they are one of a relatively sparse main cast.

- However, if they are a supporting character it could be more effective to have them static so there is more focus on the main character. This also doesn’t mean that they have to be completely two-dimensional, they can still be multi-faceted and have a meaningful impact on the film without a major character evolution.

Simply be careful that the sidekick character is still their own person and not a pale imitation of the hero. They must always have a value that goes beyond their existence as a sidekick.

Contrasting With the Protagonist

When writing a sidekick as their own person it is also important to make sure they contrast with the protagonist.

- Contrasts can come in a variety of forms, from being different visually to being a different species (such as a robot, animal, or alien companion).

- Or the contrast could be in personality or morality. Perhaps, for example, the hero is pure and good while the sidekick is morally grey.

Not only does this make each character more complex in their own respect, but it also helps drive the story forward. Perhaps, for example, this contrast forces the protagonist to look at the world differently and change their actions.

This helps keep the characters clearly defined as well as showcasing the protagonist’s traits and background. Having a sidekick as a foil to the main character can also help form the audience’s opinion of the protagonist and highlight some of their more diminished traits.

- For example, in Shrek, Donkey’s happy-go-lucky attitude is the perfect foil to Shrek’s pessimism.

- Donkey is the more likeable character. But Shrek’s stark contrast with him makes his anger and annoyance funnier as well as occasionally allowing the audience to see a softer side in him.

However, the characters must also still complement each other. If they are old friends then they should be compatible. Otherwise, their relationship is not realistic, which will undermine the dynamic.

Contrastingly, if they have been thrown together despite having clashing personalities, perhaps through a disaster they need to fix, they should still have chemistry. You want your protagonist and sidekick character to hit that sweet spot; compatible enough to get along well with each other but different enough that they bring out different sides of each other that others wouldn’t.

The Sidekick’s Motivations

Another aspect to consider when writing a sidekick that is distinctive to the main character is what their motivations are. Just because they are on the same path it does not mean they are on it for the same reason.

- A different motivation makes your sidekick more complex by giving them a background to base their motivation on.

- Contrasting motivations can create conflict between the protagonist and sidekick and also force emotional growth and character development through compromise. This drives the story forward.

Sherlock Holmes and John Watson, for instance, don’t solve cases for the same reason. John’s motivations are more humanitarian while Sherlock’s are intellectual. This causes constant clashes. Ultimately though, they still work well together and are forced to look at the situation through each other’s eyes, coming together to solve the case in front of them.

A ‘Main Character Moment’

To write a sidekick that is complex and well-rounded it is often important to give them a ‘main character moment’ or a moment in the spotlight.

This moment is often critical to the story and particularly, the climax.

A potential example is self-sacrifice. However, when writing a sidekick sacrificing themselves for the hero be careful not to reduce them to a plot device to motivate the protagonist. Fully develop all consequences of their sacrifice (often death, for example) and the emotional impact. It is a chance for a meaningful and surprising moment in your story.

This moment can also be when the sidekick finally comes into their own.

- In The Lord of the Rings, for example, Sam is still a main character but definitely a sidekick to Frodo.

- After spending most of the journey as a constant support to Frodo, Sam finally gets a moment where the audience fully sees exactly how brave and loyal he really is and ultimately saves them all.

Of course, some sidekicks are secondary characters and may not have the opportunity to become a martyr or save the world. However, it is still important to not have them be expendable. They still need to have a meaningful impact on both the protagonist and the story.

Types of Sidekicks

The Joker

One of the most common types of sidekick is ‘the joker’. They are the one of the duo that provides comic relief. This is often a very important role, whether your film is a comedy or you want to add some wit or dark humor to a more serious story.

However, writing a sidekick as the comic relief can sometimes allow for a lack of development, especially as they are carrying all the comedy. This can also happen if they are always the butt of the joke or their dialogue is purely one-liners.

A lack of full development isn’t necessarily a bad thing, as the character is only for support. However, a well-written comedy sidekick will still have their humor balanced with something else.

- For example, in The Mummy and The Mummy Returns Jonathan is the sidekick to the main couple.

- He is half dragged on their adventure and half in it for the treasure.

- He provides a lot of the comedy throughout the films through his loveable cowardice and greed.

- However, this comedy is ultimately balanced by his family love and loyalty, which also clearly drives him.

- He has a purpose and connection to the other characters beyond his comedy value. He, therefore, feels like a worthwhile and persuasive addition to the cast and story.

The Muscle

Often the other half of brains and brawn, ‘the muscle’ sidekick’s role is usually to protect and defend the protagonist or at least be useful in a fight.

Writing a sidekick as the muscle of a duo does not have to be stereotypical or restrictive. It can still allow for an interesting and complex character. For example, they could be a violent or disillusioned character whose good at fighting because of a hard life or dark background.

Or they could be a gentle giant who just happens to be strong. In The Princess Bride, for instance, Fezzik the giant is an extremely loveable character who’s main and important characteristics actually end up being his kindness and inquisitiveness rather than his brute strength.

The Brains

A brainy sidekick is often very intelligent and resourceful. They are there to solve the protagonist‘s problems or help get them out of sticky situations.

This could be in terms of technology (like Q in James Bond) or an expert in a certain field relevant to the main plot.

It’s important to write a sidekick with a background or personality that’s developed enough to explain this intelligence. A sidekick with an inexplicable amount of knowledge can feel jarringly unbelievable.

It’s also better not to reduce them to their intelligence.

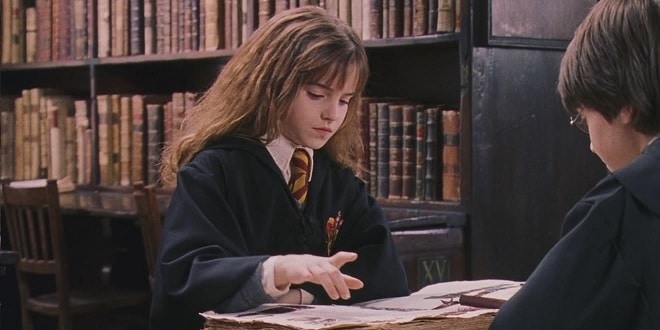

- In Harry Potter, Hermione is definitely the ‘brainy’ sidekick.

- She is happy to do all the research and often gets Harry and Ron out of tight spots.

- However, arguably, Hermione’s character definition can lean too heavily towards just being there to help Harry and Ron.

- Ron, after all, is given a rich family background right from the start, whereas Hermione’s is more opaque.

- Overall, the story’s breadth addresses these issues. She ultimately does have other aspects of her personality that shine through.

- But it shows how a sidekick character can easily become in service to the protagonist if not carefully developed enough. The development will come in acute moments, which you will need to pick carefully. It’s not about the time given, it’s about the use of that time.

The Humanizer

‘The humanizer’ sidekick is almost always a contrast to the protagonist. This is often a stark contrast to an anti-hero protagonist, who the sidekick sees the good in and encourages them to follow that part of themselves.

This can allow for not only more complex characters but also a more interesting dynamic between the sidekick and the hero. It allows the audience to see how multi-faceted the protagonist may be as they see them through the eyes of the sidekick, while also experiencing the emotional impact the sidekick may have.

- For example, in the Pirates of the Caribbean franchise Captain Jack Sparrow is self-serving and always out to fulfil his own goals.

- However, both Elizabeth Swan and Will Turner still see that he is an unusually considerate pirate who sometimes uses his nature for good.

The Friend

‘The friend’ sidekick embodies a lot of the traits that a sidekick is known for. They are loyal, and reliable, and will follow the protagonist anywhere.

It is always effective when writing a sidekick character to have an aspect of this type. Even if they start off as a reluctant duo, the friendship is something that can develop throughout your story.

This will also add another layer of depth to your characters, as they gain their own reasons for being loyal to each other.

- The traits of a friend are best seen in Sam in Lord of the Rings. He never wavers in his love and loyalty for Frodo and their friendship is what carries the story.

- Even after being sent away, he ultimately returns to save Frodo, making him one of the most famous sidekicks in cinema and literary history.

In Conclusion

The sidekick character is ultimately a way of diversifying your story and accentuating the protagonist‘s journey. It is, after all, how the protagonist relates to those around them that demonstrates the full extent of their character. It can be hard to represent this nuance when a protagonist rides solo.

This one-note feeling can also extend to the script’s tone. And a sidekick character can help diversify this tone, adding, perhaps most typically, comedy, for example.

To write a sidekick character, you must put in all the steps you would to write a main character. What will their journey be? Where will they prove themselves? How will they change throughout the story?

There will obviously be a practical difference in how much space, time and perspective you give your sidekick character compared to the protagonist. But in order to be convincing they must be as well-rounded and realistic as the character they’re resolutely by the side of.

– What did you think of this article? Share It, Like It, give it a rating, and let us know your thoughts in the comments box further down…

– Struggling with a script or book? Story analysis is what we do, all day, every day… check out our range of script coverage services for writers & filmmakers.

This article was written by Tallulah Allen and edited by IS Staff.

Get *ALL* our FREE Resources

Tackle the trickiest areas of screenwriting with our exclusive eBooks. Get all our FREE resources when you join 60,000 filmmakers on our mailing list!