When we watch a film or TV series, we’re often aware there are multiple storylines running concurrently but take them in as second nature. This is the benefit of TV storytelling after all; the ability to cover many different plots within one cohesive story or world. In the screenwriting process, these overlapping narrative threads are typically referred to as A, B and C plots.

A, B and C plots descend the alphabet by order of importance. So your A story is the most important but B and then C play crucial parts too. TV writers use ABC stories because it’s difficult to sustain a single narrative for 40 minutes plus, in terms of both writing enough material and keeping bums in seats. So how do you use A, B and C plots in TV screenwriting? We break down the core elements of what you need to know.

Table of Contents

- What’s the A Story?

- What’s the B Story?

- What’s the C Story?

- Why Not Just Stick to the A Story?

- What are AAA Stories?

- How Many Beats Should You Write in Your A, B and C Stories?

- How Do You Weave Together Your Narratives?

- 1. Connecting Stories by Theme

- 2. Cutting For Pace And Tension

- 3. Cutting For Dramatic Irony and Comedy

- 4. Intersecting Plot Lines

- How Do A, B and C Plots Intersect as Your Story Comes to a Head?

- In Conclusion

What’s the A Story?

So firstly, the A story is the real focus of your episode. It surrounds the central concept of your show.

- The A story essentially reinforces the promise of the premise.

- In a murder mystery, for example, the A story asks, “who did it?”.

This is where the main protagonist seeks their main goal. And it requires the most story beats to achieve a compelling character’s journey. As such, the A story will have the most screen time.

The A plot is the main thread of your episode. So you’ll usually open with it and then cut to the B and C plots later. The A story is the anchor you always return to as it’s carrying you through the episode.

In a detective show like Law and Order, for example, the A story follows the case of the week. It’s the main driver of the narrative, even if the supporting arcs make the story more interesting as a whole.

What’s the B Story?

Out of the A, B and C plots, the B story is often more character-driven and more emotional. It contains fewer story beats compared to your A story and has less screen time. For instance, it might be a romance, key friendship or personal issue as experienced by your protagonist.

- However, the B story doesn’t have to be a secondary story experienced by your main character, it can also be driven by secondary characters.

- It’s usually separate from the A story but will tie back in at a later point.

- It also typically mirrors a thematic point of the A story, consequently enriching the main narrative.

The B story reflects on the protagonist by exploring other characters and/or avenues of the story world. The protagonist is still in view, but by expanding the scope a little we get a more rounded and better view of them.

What’s the C Story?

Finally, out of A, B and C Plots, your C story is the smallest thread. It’s the arc you allocate the fewest beats and the least screen time to. It carries the least weight in your episode and is the least critical to the overall narrative.

The C story is also often lighter and more comedic than A and B plots. For this reason, it’s also known as a “runner”. Within half-hour comedies, the C story may literally just be a running joke, as the name suggests. The Office‘s C stories, for example, (like office pranks of jello-covered staplers) alter in form but garner the same kind of laugh.

In some cases, however, C stories may become important as they develop into B or even A plots in later series. The C stories aren’t totally irrelevant to the A story. They should, in some way, reflect on it, even in a minor way.

- For example, the pranks in The Office are reflective of Jim’s attitude to office life and his antagonistic relationship with Dwight.

However, by being down the pecking order C plots have some licence to be relatively small additions to the overall narrative.

Why Not Just Stick to the A Story?

If you were to write an all-A-story script, the pacing of your show would, in fact, stall.

- The balance of different plots allows there to be some structure to the storytelling.

- Moreover, it gives depth and balance to the protagonist arc. It fleshes out the world around them, sharpens their context and, therefore, heightens the themes.

If your story is made up only of an A arc, it runs the risk of seeming one-note, relentless in its pursuit of one character, one arc, one storyline.

Sticking with only one narrative (one protagonist), however, can be more effective when you want an emotional pay-off. As you’re sticking with one character’s experience, it often feels more intimate.

TV audiences are typically accustomed to rapidly cutting between A, B and C plots. So disrupting that dynamic by devoting multiple pages to a single plot line can make a strong statement.

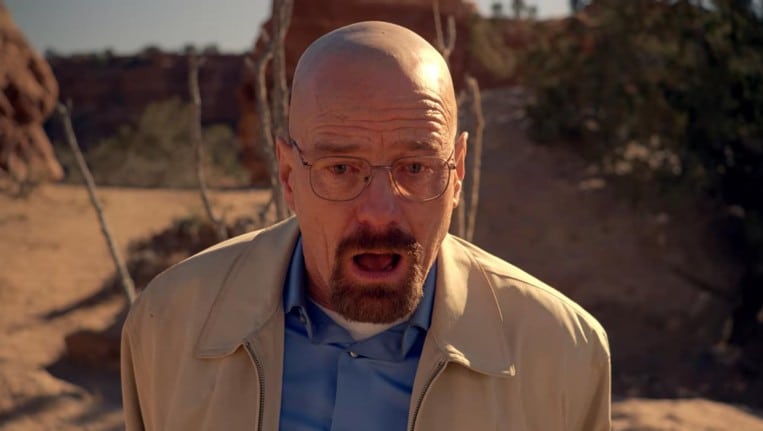

That being said, focusing on only your A story pressurizes your narrative. Your A story better be pretty compelling and special in order to keep the audience focused. This kind of writing is certainly possible. The first half of Breaking Bad’s Ozymandias episode serves as a good example of it, for instance.

However, it’s not sustainable for an entire series. Moreover, it must come at the exact right point in your narrative; an intense moment that all the different narrative threads have been building to prior in the series.

For this reason, writers use B and C stories to allow the A story to breathe. And in comedy, for instance, B and C stories make the A story funnier, adding in more running jokes and different sources of humor.

What are AAA Stories?

As opposed to writing A, B and C plots, you may hear writers also discussing the AAA format. Episodes utilizing the AAA structure have three storylines with equal weight in the episode. No one character fills the episode, all three separate storylines function as main A narratives.

This structure is rare and generally isolated to ensemble shows. One example would be Modern Family. Here, we watch different families in comedic units, each of which is equally important. Their stories intersect but are given equal time and attention.

The AAA format is relatively uncommon for dramas. Game of Thrones almost achieves it, linking arcs loosely. However, when you really break down each episode, one story ends up taking center stage and the show ends up back with A, B, and C plots.

The reason AAA is so uncommon, particularly in drama, is because it requires three stories of A quality. This means more beats with more characters and more goals. Generally, audiences gravitate to particular characters and particular storylines. To effectively balance out all storylines equally is no easy task. By no means does that mean it’s not possible though.

However, typically these AAA stories will have a larger overarching protagonist or goal.

- For example, arguably the family is the protagonist of Modern Family.

- Whilst the city of Baltimore, for example, is arguably the central driver of the story in The Wire.

So if you’re seeking to create an AAA story, focus on what or who the true protagonist of the story is and work to support that with the A arcs. These arcs might seem like the main focus but, in turn, the real focus sits above and keeps these arcs in check.

How Many Beats Should You Write in Your A, B and C Stories?

When weaving your A, B and C plots together, they should be balanced within each act. This will mean that no single act is too heavy with one storyline.

- In an hour drama, your A plot might have three to four beats per act, the C story might have two and your runner only one.

However, the number of beats can depend on the pace of your genre. For example, an intense thriller will likely include more beats per act than a light drama.

- The traditional ABC format perfectly suits half-hour comedy shows like Seinfeld. Seinfeld in particular includes a lot of C stories; lots of running gags. Although these stories are not fleshed out they often have small arcs.

- For older, two-act sitcoms like Frasier, however, you’ll generally only find space for an A and B narrative.

- Whilst for short kids animated shows or short films you’ll generally only have an A story, with the exception perhaps of a small running gag. This is obviously due to time and space constraints on the page.

Each narrative thread should be revisited in every act (typically five) of your episode. This is simply because revisiting a C story you haven’t seen for 20 pages loses the audience. The exception is if you have a particular narrative reason to delay cutting back to one narrative, perhaps to increase suspense, for example.

How Do You Weave Together Your Narratives?

When writing episodic TV, the goal is to avoid “filler” narratives. All your stories should work in concert and remain related to allow the stories to cross over and reconnect later in the timeline.

- One way to achieve this is by writing each storyline separately, ensuring each A, B and C plot has a central conflict, plus a beginning, middle and end of its own.

- Once you have the separate threads you can work on weaving them together.

To do this, you may use a beat sheet.

- This allows you to get a clear sense of how the entire episode will flow beat by beat.

- You may write beats on coloured index cards, using a different colour for each different narrative.

- Place a beat or two from each story in each act, then try to get a sense of how each arc informs the others.

Remember to keep your beat sheet clear and simple. You aren’t trying to sell your entire story (this isn’t a treatment!) you just need a general overview. Beats don’t generally contain too much action description or dialogue, they just give a headline idea of what the purpose of this beat is in moving the story forward.

By seeing where each plot arc manifests (and, in turn, where it doesn’t) you will see the gaps that need filling, where the balance is or isn’t successfully struck, and how evenly weighted the narrative is between the three different plot arcs.

But once you’ve got your beat sheet, how do you choose where to cut between your A, B and C plots? There are a few possible ways to connect your narratives…

1. Connecting Stories by Theme

The traditional way to weave together ABC narratives (as in half-hour comedy shows, for example) is to have a thematic throughline in your episode. Then, a different character will drive each thread.

The A, B and C plots help to separate themes or aspects of the overall theme that the episode explores.

- When we cut between narrative threads we usually switch to different characters. Although it’s also likely your stories will intersect and characters will make cameos in scenes owned by other narratives too.

- You choose the points at which your stories cross over in order to heighten the contrast between characters or events, in turn exploring your theme.

Whilst this is most prevalent in comedic shows and sitcoms, it’s also often present in the best of dramatic writing. In this instance, the episode will, for example, pursue a multitude of different plot and character arcs. And each arc will be in line with the overarching theme of the episode. This, in turn, will then connect to the series themes and overall narrative.

The Wire is an example of a show that does this brilliantly. It will tackle a particular sub-theme (eg “Alliances”) of its larger series theme (eg education) in each episode. All (or most) of the plot arcs will riff on this theme in a different way. And so ultimately we get a multi-faceted take on the concept.

Theme can be both a nifty and powerful way to tie different arcs together. Remember though that the theme is different from the show’s premise. The theme is the throughline for a particular episode, whereas the premise is the overarching concept of the series. The two are of course intrinsically symbiotic but are not the same.

2. Cutting For Pace And Tension

Another reason you may decide to cut between narratives is to increase or decrease an episode’s pacing or tension.

- By cutting between multiple storylines more slowly, for example, you decrease the pace of your show. This could create a sense of dread or increased suspense when you only follow a single narrative thread.

- In contrast, cutting between A, B and C plots faster will increase the pace. The shorter your scenes and the faster the cuts the faster-paced it will seem. The same trick is used in montages, for instance.

How you cut between different arcs all depends on the intention of your series and its tone/genre.

- If you’re writing a drama, where character development and internal conflict are important in driving the story forward, then spending enough time with each character and arc is important.

- However, if you’re writing a thriller, cutting between varying external conflicts at the right times will likely create more tension and excitement.

How do you know when is the right time to cut for pace? Well, think of variation as being key. You don’t want to give your audience too many action scenes one after the other, for example. Even if you want to maintain tension, think of another way to do this that’s different from what you have just presented.

Whatever the genre or intention, it’s important to include a balance of pace overall. Too much of one tone will likely leave your audience craving variety. This will consequently leave them numb to the one tone you’ve chosen to pursue. Variation and balance is key to guiding your audience through smoothly, whether you’re intending to thrill them, scare them or make them cry.

3. Cutting For Dramatic Irony and Comedy

For comedy, the switch between storylines itself can be a device to service dramatic irony.

- One example might be a cut from an A character saying “Jane’s doing great!” before cutting to Jane bawling her eyes out in the B story.

- The juxtaposition between narratives adds to the humor of the episode.

These kinds of cuts can also be a useful transition from one plot line into another. After we’ve cut to Jane in the B story we could stick with her for a couple of scenes, for instance.

Comedy is the lubricant in this regard. Humor drives the purpose of the cut but that purpose can often be a handy way into the other sides of the story, helping to balance it out overall.

Using comedy in this way is a good method of making sure the scenes are in dialogue with each other. When using A, B and C plots this is essential. These cuts and intersects must feel in conversation with each other, even if they’re dealing with completely different characters and/or contexts.

Dramatic irony can also be a way to cut effectively and highlight the difference between two plot arcs. For example, in Breaking Bad, Walt’s story is often cut with Hank’s pursuit of him (not knowing he is Heisenberg). This creates tension in the narrative; a tension we imagine will pay off sooner or later in the eventual coming together of the different arcs.

4. Intersecting Plot Lines

Some shows weave their ABC stories by starting in parallel to each other, initially branching off in adverse directions and then intersecting later in the episode for the payoff.

This structure is common for comedy shows, particularly ensembles, because two or three disparate storylines swerving in and out of themselves is often in itself comedic.

This is especially true when narratives begin in strange places. The audience is left wondering how on earth all these pieces will ever converge. The surprise, reveal or punchline comes when we figure out how they all intersect at the end.

A good example of this comes in the Modern Family pilot. The three families are separate and seemingly unconnected, until the twist reveals they’re all part of the same family. Thusly, when we look back at the different storylines we find new relevance in them after knowing they were all, in the end, connected.

How Do A, B and C Plots Intersect as Your Story Comes to a Head?

It’s useful to think of weaving your A, B and C plots like conducting an orchestra. As your episode hurdles to a close, you may want to bring in additional storylines to allow for a dramatic crescendo.

- TV writers set up ABC narratives so they can build together structurally and then pay off at the end of the episode.

- As the show progresses, we discover how all the elements come crashing together.

- This may be in a funny way in a comedy or in an emotional way in a drama, for example.

So whilst each story arc is separate, they must all reach their concluding notes at the same time and typically, overlap with each other. Think of storytelling in this regard as completing a journey. You are starting out from one point, going on an interesting and fulfilling detour but ultimately ending up at the place you intended.

All arcs are heading in the same direction, even if they take vastly different routes there. The A story will still take pride of place in the narrative. However, the B story will be pressuring down on the A story, with the C story skirting around the edges.

These different overlapping arcs create the sense of a lot happening at once. And this gives your story’s conclusion the feeling of crescendo that it needs to finish satisfyingly. This might happen within an episode (like in a contained sitcom episode for example) or within the series overall. Either way, it’s about completing the different story arcs at once (and you must complete them all), putting a rewarding full stop on everything.

In Conclusion

When figuring out the structure of your TV series, it is always worth breaking down the structures of similar shows as a gauge for how to pace your own script.

Sitcoms, perhaps most of all, demonstrate the effectiveness of A, B and C plots. This is due to the tight frame for telling the story within, the fact that the setup is typically the same for each episode and the many-episode format of a sitcom series. In this context, A, B and C plots serve to keep relatively simple plot lines engaging.

But dramas too need different plot arcs to support the primary narrative, themes and protagonist arc. The successful execution of differing plot arcs all coming together to provide a singular conclusion can be one of the most exciting parts of watching TV or film. And the work to make this conclusion as powerful as possible comes in the correct balancing of the arcs throughout the story.

Ultimately, storytelling is cohesive and not piecemeal in this regard. Yes, an overarching narrative arc guides your story. But without the proper support, pacing and balance this narrative arc runs the risk of boring your audience, no matter how thrilling or interesting it may be in theory.

– What did you think of this article? Share It, Like It, give it a rating, and let us know your thoughts in the comments box further down…

– Struggling with a script or book? Story analysis is what we do, all day, every day… check out our range of script coverage services for writers & filmmakers.

This article was written by Lyra Fewins and edited by IS Staff.

Get *ALL* our FREE Resources

Tackle the trickiest areas of screenwriting with our exclusive eBooks. Get all our FREE resources when you join 60,000 filmmakers on our mailing list!

Using a light gray typeface makes it very hard to read. Do better. Thanks.